“I can’t figure out why primary care is dying, and I’d like to resuscitate it,” said Dr. Garrison Bliss, summing up his founding of a boutique medical clinic.

We were in a little café on the third floor of the Medical-Dental Building on Olive, below the Qliance offices on 16. Bliss had just taken me on a nickel tour of his clinic, from its peaceful waiting room to its lab, X-ray room ($17 per reading), and even the in-house laundry room, where a load of full-coverage gowns were cycling in warm suds. Now, we were getting coffee. Strike that. I was having coffee. Bliss got fruit juice.

I was down visiting Qliance after reading “How American Health Care Killed My Father” (Atlantic Magazine, September 2009). In it, David Goldhill wrote something startling to me: “The average insured American and the average uninsured American spend very similar amounts of their own money on health care each year–$654 and $583, respectively.” He also mentioned, approvingly, that “Qliance Medical Group, for instance, now operates clinics serving some 3,000 patients in the Seattle and Tacoma, Washington, areas, charging $49 to $79 a month for unlimited primary care.”

The Qliance fee scale is graduated for age–I’d be looking at $768 per year for primary care, which, other than an appendectomy back in high school, is all I’ve ever needed in life to this point. Last year I paid over $3,200 in health insurance premiums on Costco’s small business insurance plan. I saw my doctor once, for a physical.

This is the kind of story that makes Bliss’s eyes light up. He calls our health insurance dependency “learned helplessness,” and likes to reference Marcus Welby when talking about the Qliance difference. “You can design this so that 80 percent of American can pay for primary care out of pocket. And the other twenty percent could do it with some subsidy,” he argued. “I’d like to prove that.” His first point is that whether you’re insured or not, if you want or need quality primary care, you’re mostly out of luck.

“Primary care docs are living on a shoestring, they don’t have adequate support staff, they don’t have time–that’s the biggest thing, time. Today they get eight minutes a patient. We’re talking to someone right now who’s seeing 40 patients a day,” Bliss added, with a “What can you do?” expression.

“The only reason primary care docs are in a big clinic is so they can refer patients for all the expensive stuff. They can order MRI and CAT scans, and all the profit will be generated through those machines, and if you’re not using those machines enough, you’re a pariah in your clinic. You’re the ‘unproductive’ one. You’ll be getting a note from the clinic manager.”

Qliance, in contrast, is all primary care. Any time you have the cold or flu, wake up not feeling well, have a minor accident and need stitches, sprain your ankle, or pull a muscle, Qliance offers same- or next-day appointments (and 24/7 phone consultation). In the clinic, they do blood draws for lab work (lab work that is sent out is billed à la carte), “EKGs, joint injections, skin biopsies, wart removal, wound care, PAP smears, and spirometry.” Generic medication is provided onsite, and billed at cost.

Whether Marcus Welby really had that kind of time on his hands or not, the Qliance model stands in sharp contrast to the productivity-driven clinic: “The average doc or nurse practitioner here works about an 8-hour day,” Bliss explained. “The office visits are booked in 30-minute intervals. Physicals are given at least an hour–we have some patients we know are going to take two hours. We try to set up our day so we can deal with emergencies, so we’ll have two or three physical exams scheduled sometime during the day, and then everything else is filled in with 30-minute appointments.”

On any given day, there will be four to five empty half-hour slots so that people who come down with something–a cold, cough, fever, infection, sprain, headache, stomachache–can get in. People with chest pain might just walk in. “We try to mix up the cultures a bit,” Bliss said, with the idea that family practice doctors can consult with other practitioners at the clinic.

There are two levels of Qliance care, Q1 and Q2, with the higher level serving patients who have chronic illnesses, and who may require periodic hospitalization. While Q1 patients who need hospitalization are guided “remotely” (through Qliance phone coordination with the emergency room or admitting physician), hospitalized Q2 patients are included in their Qliance doctor’s daily rounds.

“We come by every day and check on you and talk to you,” said Bliss. His patient load of about 500 is made up largely of Q2 patients. Doctors with primarily Q1 patients max out at around 800. The lower patient load is tied directly to patient care. “With a third of the panel of patients, or a quarter of the patients, that most doctors have, we’re very busy,” said Bliss. Besides in-person consultation, his doctors are available by phone and email.

Part of the rationale behind the monthly fee system, besides its regular, stable cash generation, is to give patients peace of mind around medical costs. “When a patient leaves us, they should have a pretty good idea about what their adventure with us cost them. For most people, the adventure costs nothing,” Bliss said. “If it involves what we do, with our brains and our hands, it’s free [with the monthly fee]. If you need sutures, you get sutures. If you need a splint on your fracture until you can get to the orthopedist, we’ll splint you.”

Most other services are provided at cost: “If you need a boot because you fractured bones in your foot, we’ve got the boot, we’ll put the boot on, and we charge you our cost for the boot. There’s very little in the surprise category. If you want to know what your labs are going to cost you, we can compute that for the most part, even if we’re not doing them ourselves.”

Why would this extra-care model work? Bliss argues that it’s because most of us are starved for primary care, and getting thinner.

“The thing that is invisible to everybody is that the insurance world currently is expending only something around $10-$25 per month per patient on primary care. No one’s specifically told me that, but we’ve had conversations where we’ve asked, ‘If you didn’t have to insure primary care, how much would you lower your monthly charge?’ And they say, ‘Oh, ten bucks. Fifteen. We could go to $25.'”

Bliss leaned in to make his next point: “Most people have no idea how little, of that big pot of money, is actually being pushed toward the 80 percent of care that everybody wants and needs. They also don’t realize that you probably have to double or triple that number to make primary care effective again. A five-, ten-, twenty-percent increase, which is sort of what the federal government is thinking about, won’t work.”

And here is where Bliss separates from the pack on health care reform. While he agrees that health insurance is part of the problem, when it comes to primary care, he doesn’t want more coverage.

“All the policy people, with few exceptions, their idea of health care policy is health insurance policy. They can’t get escape from thinking that everything has to be fixed by tweaking insurance,” said Bliss. But for him, the inexpensive nature of primary care makes it a terrible candidate for insurance.

“The cheaper the event, the more distorted and disrupted it will be by our system of payment. At the primary care end of the scale, you actually asphyxiate the service altogether by paying for it with an insurance system. If doctors just work for the patients at that level, you spend less money and get better care. Plus, now the doctor is incented to take care of the patient in a way that feels like care to the patient. Service now matters.”

With the inexpensive 80 percent of health care–primary care–paid for on a monthly fee basis, the hugely expensive ten to twenty percent would remain to be covered by insurance. Then insurance companies, freed from the terabytes of primary care data, could focus on (and compete on) specializing in providing the best coverage for, say, bone marrow transplants.

People who couldn’t afford primary care, he suggested, could receive a subsidy. “Like food stamps?” I offered.

“Exactly,” Bliss said, launching into an extended analogy. “It would be hard to argue that eating is less important than medical care. We thought medical care was too important to let the marketplace function. But if you look at food, you realize that food is inexpensive for the most part, it’s widely available–what would happen if we insured food?”

“With food, the marketplace is controlled by the 80 percent of people who can afford to buy with cash. You have places that sell expensive, high-end food, places that sell fast food, places that sell farmer’s market stuff–the pricing models are highly evolved and the service levels are great. You put a food stamp in somebody’s hand and they become a consumer in that system–their money is as good as everybody else’s.

“If you did that in health care, so that primary care and chronic care were all managed with monthly fee systems and competed for patients, and patients decided where to spend their money, [you’d seem improvements in] services, quality of care, availability.

“In the insurance world, any customer’s ten minutes is worth the same as another ten minutes, and there’s an infinite supply of patients waiting. There’s no cost to not being open on the weekends. But there will be shortly. We plan to make it uncomfortable. If you run a clinic and you close weekends, and Qliance is down the block, you’re going to be losing market share.”

While Qliance represents a trend toward boutique health care becoming more affordable, it’s growing through a kind on pincer movement, attracting insured patients who can afford to pay for better service, and another group for whom any primary care at all is a step up. At Qliance’s new Kent clinic, Bliss said, they are working with companies that have never had health insurance, who tend to employ minimum-wage workers.

Qliance is trying to negotiate cash prices with larger health care providers for out-of-house services, but it is difficult because these institutions would be in violation of their agreement with Medicare if they priced care lower than they charge Medicare.

“A reasonable ‘retail’ price isn’t possible if Medicare is willing to pay too much,” Bliss said. “And they are. That’s why we’re in the mess we’re in. The inertia of the system is very hard to overcome in that particular area. You know, we’re working on cash mammogram pricing. But it may be that we have to break away from the whole system in order for this to work. We may need to do mammography ourselves.

“Kaiser Permanente has figured this out. They’re an insurance company that owns their own treatment system. It’s to their advantage to get their procedures done inexpensively, and to not overdo them. They have nurse practitioners who are trained to do colonoscopy, do many of them a day, and I’m sure are not being paid $1,000 every time they push a scope.”

It’s a fascinating conversation to have, and one strikingly different in tone than much of the health care debate I’ve heard about over the summer. As a health care consumer, I have leaned toward the simplicity of a single-payer, government-run system. But there is no denying that right now–today–Qliance can offer me primary care at less than the cost of my iPhone bill. If decoupling primary care from specialized medicine can work in medical practice, why not in insurance billing practice?

I asked Bliss early on if there was an idealism requirement for work at Qliance–at a venture-funded start-up, salaries are often lower than market rate. He shrugged and countered with the lower Qliance patient load. But late in the conversation he added:

“It matters to me whether the Qliance model gets adopted nationally because I think it’s better care. I have a great-uncle who invented the iron lung and refused to patent it. His feeling was that it was really important for people to have access to this machine.” He didn’t elaborate beyond that. But it is clear that he imagines Qliance, with its Q1 and Q2 paddles, as capable of delivering a healthy shock to a primary care system in danger of shutting down entirely.

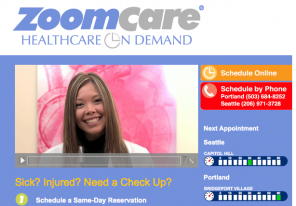

Heading to Blue Moon Burgers on Broadway, on Capitol Hill, the other day, I passed a “store” called ZoomCare, that upon further inspection sold health care. Eating at burger joints always puts me in the mindset to research low-cost health care options, so I resolved to take a look at this interloper once back at the office.

Heading to Blue Moon Burgers on Broadway, on Capitol Hill, the other day, I passed a “store” called ZoomCare, that upon further inspection sold health care. Eating at burger joints always puts me in the mindset to research low-cost health care options, so I resolved to take a look at this interloper once back at the office.