A Discomfiting Presence

In Corner Conversations & Matters of State, ACT’s second set of Pinter shorts festival (which closed Friday), curators Jane Kaplan and Frank Corrado delivered a sophomore survey of Pinter’s body of work that provided a satisfying capstone to the celebrations. This survey included essays, bits of lecture, context, and commentary.

In his opening remarks Corrado contextualized the shorts in the world of the British comedy stage review, specifically “Beyond the Fringe“, and the influence of sketch writer and performer Peter Cook. With no more further ado than a harmonica solo by Charles Leggett the nimble cast launched into a series of bits featuring mostly older and somewhat mentally unstable Brits.

The Black and White, Umbrella, and Last to Go took advantage of Pinter’s skill in dialogue that discussed almost nothing in phrases that turned back on themselves with multiple variations. Suzy Hunt was a standout in the first of these with the clever detail of her business. She repeatedly sucked at dentures, cleaned a fresh restaurant spoon with her hem and eyed the world with active, suspicious glances. Meanwhile Julie Briskman wisely underplayed on her side of the milk bar table.

Interview shifted things from the absurd to the disturbingly silly as David Pichette’s porn shop proprietor slowly revealed his unhinged ulterior intentions. There was pleasure for audiences familiar with Pichette’s work to watch this hissing maniac uncoil from the actor’s usual dignity.

Hunt returned as a dotty and manipulative derelict in Bus Stop, the production’s weakest offering. This preceded the evening’s hidden track (kept off the program the audience was asked to say nothing about this piece, which was less funny than illustrative in its subtle contrast with the rest of the evening’s sketches.

Leggett’s harmonica interlude, which was such a delightful surprise at the end of the first set of sketches became a bit monotonous and wearying in its regular use as set change cover in this round. As director, Kaplan justified this choice in the second half the evening, which lost the harmonica as the pieces took a more serious bent.

The fulcrum sketch was Night. Contextualized by notes on Pinter’s marital struggles, we saw a very human snippet in which a couple (Briskman and Leggett) reminisce about their first meeting. This being Pinter the past is not a singular thing or a point of consensus here but a stage for playing out the couple’s current tensions, conflicts of personality, and abiding grievances through disagreement.

With an acknowledgement of Pinter’s political life and a quotation from his Nobel Prize acceptance speech the cast launched into a pair of shorts that cut to the bone on the inhumanity in government. Precisely, from 1983, slipped from ambiguity into discomfiting clarity as men in suits discussed figures. Ben Harris and Peter Crook carried a waft of casual malevolence from their appearance in No Man’s Land. Harris, who was all but inaccessible as Foster (and appropriately so), made a case to send him some meatier roles.

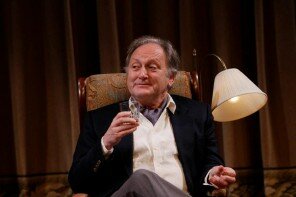

In Press Conference Corrado played a government minister answering questions on policy with horrifying answers that were nearly masked by his official language. Corrado took on the minister’s role sounding more like an actor than a politician (an admittedly slight distinction). One wonders whether greater verisimilitude would have masked the enormity completely or lent it more power.

Horrors of more typically Pinterian absurdity define Tess, a rambling almost-logical monologue that spirals away from sanity. Briskman’s ingenuous approach gave full power to the shock ending.

The ending of this second set of sketches was less shocking than jarring; it wasn’t even theatre. The final word was given to Pinter himself in a video clip of his live televised performance of Apart From That. The script, a Pinter-précis of the utmost simplicity, was a near-perfect coda to the evening and the festival itself. That the performance featured a cancer-ridden Pinter was key to its success, but it also fascinated as performance.

Pinter is in the company of Checkov and Beckett in the degree to which his plays depend on presence—the experience of people remaining in one another’s company. Presence creates an opportunity for violence but in his world the only thing worse than being together would be to be parted. Yet, here in this final piece the performance itself questioned the nature of presence and thus the nature of community, citizenship, and our relationship to every other living person.

Written as a phone conversation and staged with Rupert Graves playing the other role via a live feed from a distant studio, the video of this sketch could hardly be more separated in time and space from ACT’s audience. As you read this article, however far removed you may be from ACT’s Pinter Festival, these questions could not be more pertinent. What is it that separates you from me and everyone else? What is it that connects us—writer and reader, the callous government minister and the woman scrimping in the milk bar? How do we live together and how do we feel about the horror and the menace of everyday? As the festival wraps up this weekend these questions remain implicit.