If you’ve never seen Angels in America you need to see Intiman’s current production (at Cornish Playhouse through September 21st). If you’ve only seen the HBO film version, you need to see this production. If you’ve seen the show before you can sit this one out but you likely won’t because you’ll know that Angels in America is one of the great plays of the 20th Century. It has taken its place alongside Death of a Salesman, August: Osage County, and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (I’d also make an argument for adding The America Play by Suzan-Lori Parks to this list, but I might be in a minority). These are plays that define our national identity in terms that gain breadth from their specificity.

And yes, like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, the play is long, but also like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf it is vital and necessary that you stay for the whole performance. Plan on arriving late to work the next day if need be. The whole work is more than 7 hours of theatre. Part 1: Millennium Approaches is 3.5 hours long, including intermissions—yes, plural intermissions (Part 2: Perestroika opens September 3rd and runs in rep).

The play has a lot to say and it says it efficiently. Plot and event churn away. Famously there are even scenes that play simultaneously (an effect that isn’t entirely successful in this production). That’s how efficient it is, and yet it still takes 3.5 hours. Even if this production leaves room for improvement it’s worth it.

The play speaks of the American condition with joy, love, comedy, anxiety, and ambition all that makes America what it is. When the play debuted in the early 1990s it seemed remarkable that it did this through a story full of homosexuals and Mormons. Lately homosexuals and Mormons seem to dominate the American cultural landscape. Was playwright Tony Kushner prescient? Was it a self-fulfilling prophecy? Who’s to say—but does the play age well? The answer to that question is an emphatic yes (thus far).

What once was topical and current is now historical. Though we still fight mysterious and seemingly unstoppable viruses that rise out of Africa and wreak death and destruction in the face of fear and ignorance, the palpable fear of the AIDS epidemic now feels like the fear of the red scare Kushner references in the person of Ethel Rosenberg. It’s historical but present, if only because we never really outgrow our history. Director Andrew Russell leads his cast through the heavy meal of Kushner’s text with keen understanding and useful interpretive shades.

Intiman’s production is good but not the transcendent show it should be. The acting is mostly solid, with a cast that hails from the usual drama club of Seattle suspects. Charles Leggett delivers possibly his finest performance to date, disappearing into his role as the venal lawyer and Republican operative, Roy Cohn. Quinn Franzen is also excellent and nearly unrecognizable in the central role of Louis. Franzen’s accent fades over the course of some scenes but he lives fully inside this tightly wound bundle of intellect and anxiety. In fact he shares the one scene this production really nails. The other half of that scene is the ever-reliable Intiman stalwart, Timothy McCuen Piggee, who doubles as both—well, this is where it gets complicated.

Angels has a level of complexity that suggests something between a fugue and a 19th century melodrama. Be warned that Part 1 ends in a tangle of split ends and splicing comes late in the game of Part 2.

At the center we find a pair of couples. The most central of these are long-time boyfriends: the Jewish intellectual, Louis (Franzen), and the WASP-y Prior (Adam Standley). From the Mormon side we have the Valium-popping housewife, Harper (Alex Highsmith) and her rising star Republican (natch) lawyer husband, Joe (Ty Boice). For inciting incidents we have two diagnoses of AIDS: one for Prior and the other for the real historical figure, Roy Cohn (Leggett). Roy is Joe’s mentor and champion. Joe is Louis’s coworker.

Piggee plays Prior’s ex-boyfriend, Belize, but he also doubles as Harper’s hallucination, Mr. Lies. Roy has his own hallucination in the person of Ethel Rosenberg (Anne Allgood). There is a score of character, all told, and much doubling. Also there is an angel (Marya Sea Kaminski).

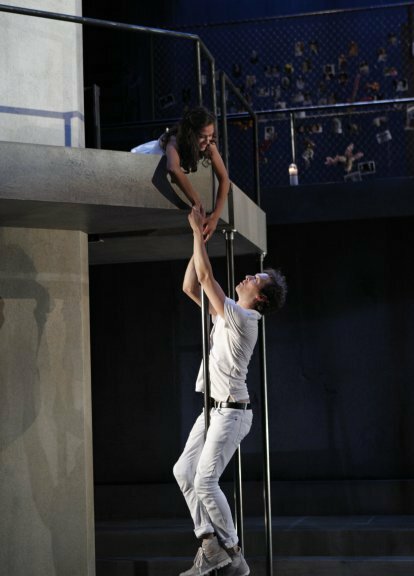

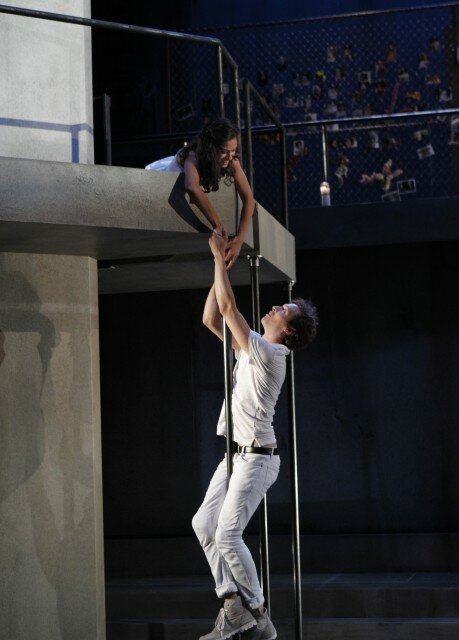

There is some great work here. In addition to the fine acting Jennifer Zeyl’s set tweaks the play’s traditional tabula rasa, evoking Greek tragedy, and both civic and eternal judgment with heavy steps, columns, and plinths. She jettison’s New York City specificity favoring thematic unity. Mark Mitchell’s costumes are perfectly researched for character, circumstance and tradition from Harper’s Mormon underwear to the big suits that hang off Roy’s shrinking frame and Ethel’s perfectly manicured ensemble.

Unfortunately the biggest moment fails. The lead-up to the angel’s entrance is powerful. Matt Starritt’s sound design sneaks up on us and then promises great things to come. Robert Aguilar’s lights open the door to astonishment. What we get is a Christmas tree topper. One can see the argument for the choice but it is neither sufficiently ironic nor adequately awe inspiring to produce anything more than disappointment, despite Kaminski’s best efforts.

It should be noted that Kaminski brings a big spark to every other scene she touches, whether playing a South Bronx derelict, a sympathetic nurse, or the friend and realtor of Joe’s mother back in Salt Lake. Few others show such consistency through their many roles. Anne Allgood shines as Ethel but drags in most of her other roles. Highsmith’s Martin Heller requires some endurance and graciousness from the audience, and even Piggee’s Mr. Lies lacks the verve of a compelling fantasy. Leggett is as good playing Prior’s Restoration era ancestor as he is in his primary role, and though Ty Boice struggles with his accent his medieval ancestor of Prior has great charisma.

For all this production’s achievements it shares the perennial Seattle theatre problem of a dragging pace. One can hear the gaps between lines that leave the dialogue feeling staccato and plodding until we get to the three-quarter mark of this first half of the play. In this scene Belize meets with Louis, who is wracked with guilt at leaving Prior when he can’t cope with the illness anymore. Louis covers his guilt, fear, and self-loathing by spewing intellectual folderol that quickly careers into blatant racism that finally drives Belize away. Franzen nails the New York pace while Piggee stays in the scene, engaged, listening, and responding through Belize’s repulsion and disconnection. This is an intensely emotionally driven scene that unearths the love and fear these men feel for Prior. Their different responses delineate the spectrum of humanity, our frailty, self-interest, compassion, and heroism. Here the cast, director and playwright find the same groove and the show fully lives up to its reputation.