Almost all of the dance works at the Next NW 2012 festival (at Velocity Dance Center through December 9; tickets) feature a movement or a tableau that seem to lodge themselves in you, like a good short story will. The six pieces are limited to 12 minutes each, so there’s a similar constraint, though you never see the same thing twice.

It might be the time of year, but a twilight eerieness (Amiya Brown’s lighting) infused more than a few works. Paris Hurley’s installation in the bar — she stands half-dressed in a bathtub, up to her knees in potting soil, while a video monitor shows a trickle of blood down a breast, being wiped away but reappearing — was unsettling. Sarah Butler’s mammoth playing-card-structure out front (30 decks, I think she said), which she built while doing the splits, seemed more cheerful in this context.

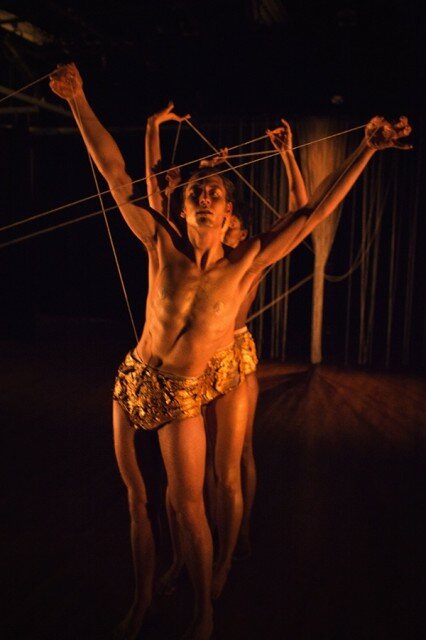

“9andOne” took a mythic approach to the theme of Real/Time, with a trio of gold-painted dancers (Ariana Bird, Matt Drews, Micaela Taylor) connected by strings from their navels to a fourth (Alia Swersky), who at times tugged at them as if the strings were reins, and was at times pulled into the trio’s midst.

The choreography by Babette McGeady, sinuous and tension-filled, incorporated the strings into cat’s-cradle formations, and also had the dancers appear to pull the strings directly through their midsection. The trio is topless and their appearance is statue-like, but except for one weightless coupling (Bird braces herself via Drews’ down-stretched arms while her legs wrap around his middle), they’re full of life and emphatically rolled shoulders.

In “Hour Hand,” choreographer and dancer Molly Sides appeared in a cloud of smoke-fog, for an almost Graham-esque piece in which the dancer tries mainly to inhabit the movements. The result is performance, a dance for an audience, but it also feels like a ritual of sorts. To a tick-tick-tick rhythm, Sides begins small, with a stair-stepping stasis walk (up on toes, then down), then the upper body joins in, along with quickly retraced side-steps. She moves throughout the space, showing you what she’s doing now…and now…and now.

“Diane” is the work from Shannon Stewart (with Mary Margaret Moore) that I previewed earlier. Watching it makes you want to go back and review David Lynch’s work as choreography — Stewart has drawn the movements from the first 30 minutes of Fire Walk With Me. Moore is unfolded, in dead-bodyweight splats, from a sheet of plastic.

Stewart and Moore trade consciousness in a tricky, compelling duet (involving two chairs) where one slumps as the other wakes. Stewart sweeps one chair around just as Moore reclines onto it — the timing has to be (and is) perfect. Three back-up dancers (Meredith Horiuchi, Jan Trumbauer, Rosa Vissers), all dressed to Lynchian nines, slowly enter and retreat through two doorways at either side — they shudder or make phone calls. Near the end, everyone enters the space, and as the lights slowly, slowly fade and Adam Sekuler’s wind vocals blow, they become a forest of untrustworthy trees.

Erica Badgeley’s “(earthworm)” featured Badgeley on a short bench, in a tank top and jeans, painted silver up to her neck. With her hands held a slight distance over her knees, she slowly, smoothly opened and shut her knees, before getting up and, using one arm, adjusting her body into new configurations, doll-like. In addition to music by Benjamin Marx, there are mutterings and rhythmic breaths by Maiah Manser that Badgeley responds to: She might, flat on her back on the floor, form a contracted U in time with the breaths.

Finally, Badgeley returns to a pool of liquid red (paint), drawn to it, one arm out, a finger extended, drawn back, thrust forward again. Then she’s in the paint, hands and feet leaving tracks as she moves away on all fours. Suddenly she turns back, rolling in red. It ‘s hard to tell how we got here, but it is gripping.

“TRE (2nd movement)” is a dance by Markeith Wiley + The New Animals that I am still pondering. Three dancers (Jamie Karlovich, Molly Sides, Calie Swedberg) are dressed in three different colored tops. The movement looks abstract, at first. Karlovich runs in circles, freezes in a fists-balled runner’s pose. But then two dancers keep initiating contact. One will line up behind the other, mimicking an upward reach; moving past, one will catch the other’s arm. It doesn’t seem to come to anything. They’re as likely to fall to the floor and begin a short core-strength routine.

Raja Feather Kelly (aka The Feath3r Theory) closed the program; the work bears a title whose length would make Fiona Apple catch her breath, and I refuse to type it all out. Let’s call it “25 Cats” for short (which is, by the way, a Warhol reference), though it also includes this song title and notes what’s known as “the 7-minute lull.” Tissues atop softball-sized balls hang from fishing line like little satellites.

Kelly, though he’s an accomplished and magnetic dancer, seems more interested here in imperfection and failure. In a light-green-to-platinum wig, a red T-shirt, and blue briefs, he dances out a portrait of someone in another world. It’s a disjointed piece energetically (with music by Michael Wall and Tito Ramsey) — he is listless, then briefly inspired. He sinks to the floor and stares off into space (a lull). At one point, he dances out invisible boxes on the floor, again and again. He leaps into the air in a spin. He exits with the music still playing, as if tired of improvising, mouthing the words “thank you.”