So I-1183 (the initiative that privatized liquor sales in Washington last year) did not bring about the free-market paradise that the state’s tipplers were promised by supporters of the initiative. (See our earlier story comparing liquor prices at various retailers.) Spirits have been marked up, in some cases significantly. What exactly has contributed to this price hike? It looks like the one-two punch of high state taxes and a distributor duopoly that’s insulated, so far, against competition.

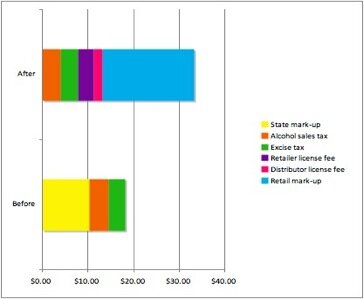

The accompanying graphic demonstrates the changes in liquor taxes before and after I-1183. At The Tax Foundation, Richard Borean explains that, before I-1183, “Washington had a markup of 51.9 percent, an alcohol sales tax of 20.5 percent, and an excise tax of $3.77 per liter, making their total excise tax rate the highest in the country at $26.70 per gallon: more than 3 times the national average of $7.02 per gallon.”

I-1183 did not raise existing liquor taxes, but instead created retailer and distributor license fees (17 percent and 10 percent respectively). The distributor license fee will go down to five percent after the first two years.

It’s true, without any retailer mark-up to replace the state’s mark-up, the combination of taxes and fees post-I-1183 would amount to lower prices. But even if retailers weren’t out to make a profit — as they certainly are — there was a proviso on that 10-percent distributor’s tax: If it did not bring in $150 million in the first year (by March 2013), the distributors would have been responsible for making up the difference. Certain distributors, says Stone, actually raised their prices during the first year to meet that benchmark.

Sound Spirits, the Woodinville Whiskey Company, and SoDo Spirits (home of “only aunthentic Honkaku shochu) all report lowering their prices in order to keep shelf prices reasonable. Steven Stone, owner of Sound Spirits and president of the Washington Distillers Guild, says that even “a small change on the wholesale level can have a big effect on the retail price.”

Yet Stone is optimistic that prices will begin to calm down in the next year or two. The $150-million minimum will no longer be a factor going forward, and in 2014, the distributors’ tax will reset at five percent for all distributors and distilleries in business now. Stone thinks the liquor market is still bearing an unfair share of the tax burden, but he is not hopeful that the law will be changed anytime soon: “I kind of feel like we might be stuck—kind of like hotel California where you check in and you can’t check out.”

Another factor driving pricing is competition—or the lack of it—between distributors. In Washington, Southern Wine & Spirits and Young’s Market are by far the two biggest players, and as such they have the ability to affect prices via the labels they decide to carry. Part of what gives distributors in general their power is that distilleries need their access; in the best case, that’s a two-way street as distributors compete to sign popular or unusual spirits.

Woodinville Whiskey’s owner Sorensen says that their distributor (Click Wholesale) “is awesome. They let us focus on doing what we do best and they do what they do best.” But for a recently started company like SoDo Spirits, not carried by a distributor, the ease of one-stop distributing through the state is a dream of the past.

Though Young’s and Southern have built, effectively, a duopoly in the state’s liquor sales market, I-1183 sponsor Costco is still trying to work its way into the distribution market. Currently, the initiative states that no more than 24 liters (about three cases) may be sold from one retailer to another in a single sale. Large retailers like Costco and Total Wine & More could elbow, in practice, into quasi-distribution but for this.

If Costco can get I-1183 amended, the penny-conscious cocktail customer could see the results in drink menu prices, as Young’s and Southern respond to a large competitor carving out a piece of the distributing market. If in the short term, the lower distributors’ tax and the removal of that $150-million minimum cut for the state — even the prospect of Costco becoming a bigger player — will all contribute to price-pressure in the liquor aisle, no serious discounts are visible on the horizon. As frustrating as it is to admit, nobody can really know where the Washington liquor market is going in the next couple of years. Not even Nate Silver could call this game.