The Seattle Symphony performs works by Mozart and Mahler on April 6 & 7 at Benaroya Hall. More details and tickets are available at the Seattle Symphony website.

Thursday evenings might be my new favorite time to catch a Seattle Symphony performance. I’m usually a Sunday matinée concertgoer, but my experience at Benaroya Hall last night may convince me to exchange all my remaining Seattle Symphony subscription tickets for Thursday night shows.

The weeknight atmosphere at Benaroya Hall is relaxed and low-key, with a smaller crowd that’s energetic and diverse. Most importantly, there’s ample space on the foyer balcony to relax on a couch and enjoy my tradition of intermission chocolate while gazing at the nighttime city views. No more cowering from the wineglass-toting hordes in a dark corner near the bathrooms!

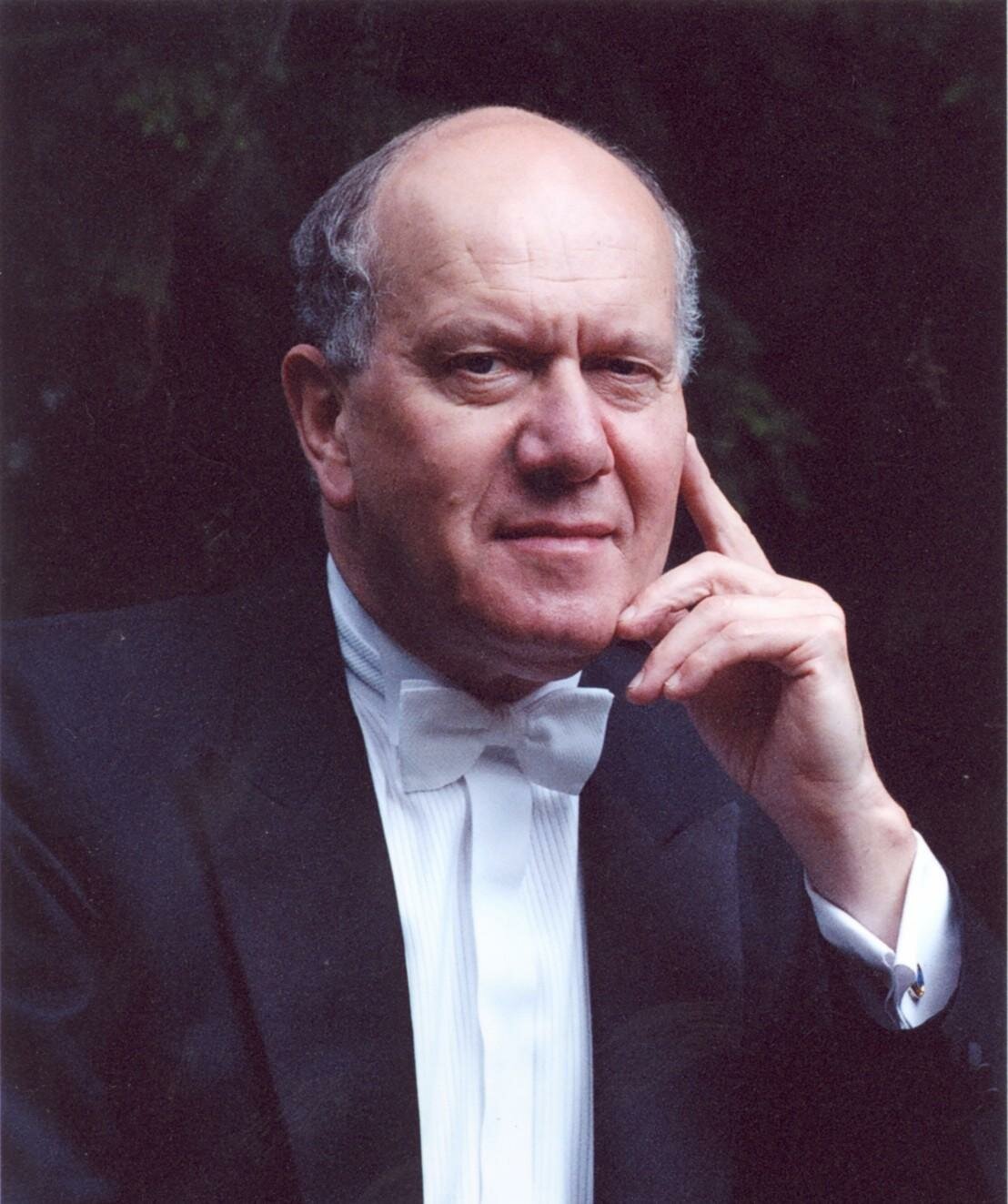

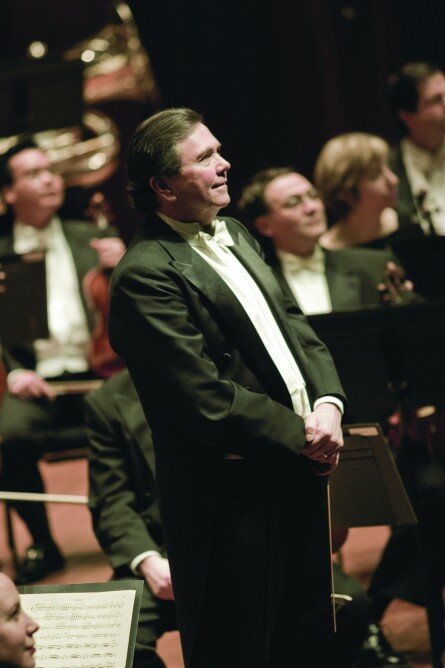

Concert hall atmosphere aside, the Seattle Symphony can make last night’s program of Mozart and Mahler shine on any day of the week. Conductor Laureate Gerard Schwarz returned to the podium for yesterday’s performance, which featured the famous Overture from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in C Minor featuring renowned pianist John Lill, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. This program will be repeated tonight and tomorrow night.

The Overture from The Marriage of Figaro was an ideal way to start off the evening of classical favorites. In Mozart’s opera, the Overture sets the stage for the madcap hijinks and comedic action to follow. Likewise, the familiar strains of the Overture provided a lighthearted introduction to last night’s Seattle Symphony program, balancing out the dramatic elegance of the Mozart piano concerto and the epic scale of the Mahler symphony. The orchestra played Mozart’s overture with a charming energy despite occasional balance issues.

Pianist John Lill brought a refined elegance to his performance of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in C Minor. Fans of the flying fingers and keyboard pyrotechnics found in Romantic Era piano concertos might balk at the relative simplicity of Mozart’s concertos, which are solidly rooted in earlier, Classical-era traditions. But under the fingers of a legendary pianist like Lill, the melodic lines and textures of a Mozart piano concerto come alive. Lill brought eloquence and meaning to every note, collaborating well with Schwarz and the orchestra to enhance the effects of one of Mozart’s most dramatic piano concertos.

The evening ended with the eagerly anticipated Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. Although the composer began writing this work he was only in his twenties, it is considered one of his finest and most beloved. The work is nicknamed “Titan” after the title of a popular novel by Jean Paul Richter. All four movements of the symphony are highly programmatic. When strung together, they create a musical tale of epic proportions. Although Mahler wrote detailed program notes to explain each movement, these are often omitted in modern performances, leaving it up to the audience to create their own storyline for the piece. During last night’s concert, I delighted in crafting my own narrative to go along with the music.

Seattle Symphony’s performance of the Mahler was an immersive journey into a world full of color, drama, and adventure. Mahler’s writing took advantage of the full range of orchestral palette of sounds. Schwarz and the Symphony painted a remarkable picture, making the score come alive. Outstanding solo work by the French horn section lent a rustic, pastoral feel to the first and fourth movements. In the dirge-like third movement, solos by members of the woodwind section cut through the somber strains of a funeral march like a knife.

I wasn’t the only one who found the Symphony’s rendition of Mahler stirring and inspiring. A young woman sitting with her date in the row in front of me spent the entire performance conducting along with the orchestra, complete with full interpretation of dramatic effects and mood changes. She probably wasn’t a conducting student or a Mahler scholar, just a playful concertgoer experiencing the music around her in a creative, refreshing way. Don’t miss this chance to be inspired by one of Mahler’s most beloved works.