(Photo: Julieta Cervantes)

Next up in the UW World Dance 2012/2013 season: Compagnie: Marie Chouinard (January 24–26, 2013, at Meany Hall).

Mark Morris recently said in The Stranger that “world class” is a “horrible term” to apply to the arts. I agree with him. Somehow the phrase cheapens art.

Still, I like world-class art. And after I watched the world-class Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet dancers perform world-class choreography under world-class lighting at Meany Hall on Thursday, I wondered:

- What makes something world class?

- How—apart from the high you get when you see it—can you tell that something is world class?

- What would it be like to live in a city like New York, where I imagine you can see world-class dancers any day of the week?

- What would it be like if these world-class Cedar Lake movers were “ours”? Would we love them like we love our world-class Seattle dancers Amy O’Neal, Jim Kent, Vincent Lopez, Carla Körbes, Kaori Nakamura, Jonathan Porretta, et cetera?

- What about the dancers we love who aren’t world class?

- How does experimentation fit into world-class dance?

- I’m not the only dance writer in town who misses (and misses out on!) a good chunk of local experimental work because it can sometimes be boring. Don’t say it’s our job, because most of us don’t get paid to watch and write. Do say “boring” is subjective and biased, because it is. Laugh when we miss it and we hear tantalizing reports from people who bet on the right horse. Cry when it robs dance companies of the reviews and the public record that could help them get grants to grow on. I’ll cry too.

- Experimentation is key. In a perfect world, there would be a place where experimentation and process is honored and enjoyed, regardless of the outcome. And there’d be a place, too, where forking over $50 for a ticket and carving an evening out of your busy schedule would guarantee you awesome world-class dance.

- Guarantee? Why on earth would anyone want a guarantee in art? Guarantees kill art.

- In writing these questions, I see that what I dislike about non-world-class works can be easily applied to this very article: Inner musings, personal explorations aren’t always interesting to an audience. They have to—what?!?! There has to be something else for them to be interesting art. A curtain speech this long is self-indulgent. I will stop. I will. Stop.

Cedar Lake’s first piece, Violet Kid, is—and not in a cheap way—world-class.

This frenzied works starts with stillness. Choreographer Hofesh Schechter’s confessional monologue wanders around as the 14 dancers stay still in a tight line at the front of a darkish stage: “Do I talk too much? Maybe if I didn’t talk so much, I’d have more friends. … In the first 15 seconds, you already make up your mind about a show. [pregnant pause] Fuck.”

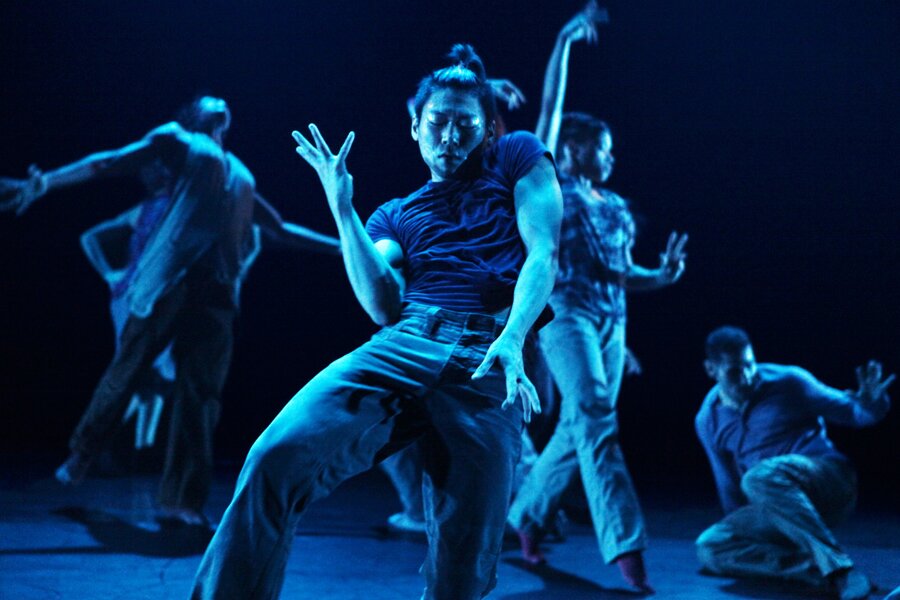

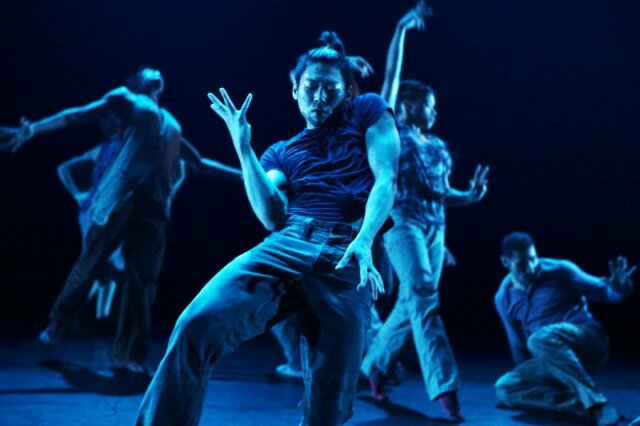

That’s the only funny moment of this work. The program notes say it’s about “man’s struggle for harmony within a complex and sometimes horrifying universe.” Sure, whatever. What amazes in this piece is not its bleak, spastic interpretation of a theme. What amazes is the layering of rhythms, rhythms that come from layered steps, layered movement qualities, layered music (percussive), layered lighting (architectural), and layered, constantly shifting group sizes. What amazes is the way these individual dancers, each with his/her own essence, move as one.

Video clips online do not convey the flavor of this work, but they do show some of the movements that Schechter has the dancers repeat over and over again, ad delirium. There’s oozing and convulsing, a up-and-down jig, a militaristic pogo dance, ape arms and boxer arms and protester arms. There’s a dash of Fiddler on the Roof traditional dance and a pinch of West Side Story jazz. While the dancers often switch between movement styles in split-second precise shifts, there is a feeling that the overall movement is unstoppable and continuous. “Dancer onslaught” my friend called one move; we loved the anticipation of watching the organic invasion gather upstage left and then spilled out across the stage.

Violet Kid starts quietly but builds quickly into an intriguing noisiness; its 40-or-so minutes include well-timed pauses and blackouts so we can rest. The dancers don’t get to rest much, though. During one of those pauses, they stand balanced on one leg, right up front near the audience, seemingly for eons. When, toward the end, we see a single dancer balanced this way, he seems so alone—and yet, not alone, as I felt the clear memory of the earlier line-up hanging in the air around him.

When the curtain dropped, I was ready for a break. There is so much going on in Violet Kid. But I would have been happy to see it several more times that night. I wanted to know who the dancers were, to follow each dancer’s thread through the fray, to connect names with these amazing artists who seemed to be able to move every inch of their bodies.

It’s hard to know who’s who from the ultra-cropped headshots in the program. And so it was a pleasure to find out that part of the second piece, Alexander Ekman’s Tuplet, played off the names of six of the dancers; we got to know their names. I found out that the “kid in the striped shirt” from the first piece, is Jon Bond, although from the way he rolled onto the stage during the second piece, he might have been named Ninja Cat Tumbleweed, so soft, and light, and fast was he.

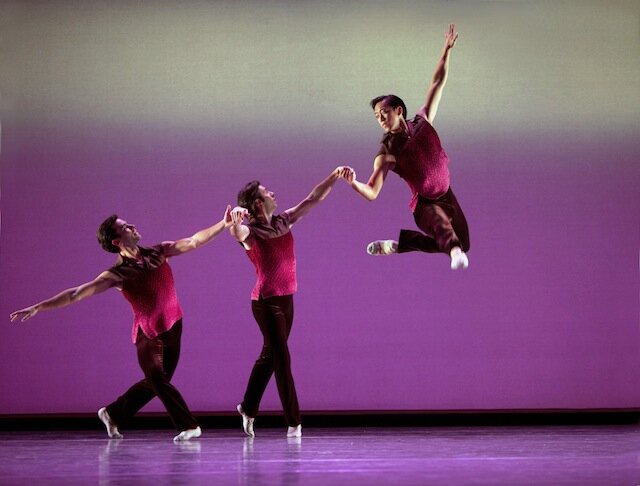

Tuplet was more relaxing for the audience. The program notes indicate that Tuplet endeavors to understand a small fragment of the question, “What is rhythm?” Since, as the voice-over tells us, “nothing isn’t rhythm,” there are a lot of possible answers. Ekman explores many of those answers through a series of vignettes, using six dancers, the white square material they dance on/with, and a background of split-screen projections. It was like a really good, fun lecture, which, seeing as how we were at the University of Washington, is fitting.

The problem with pieces that use multiple vignettes is that some vignettes pass too quickly. At one point, the group plays patty-cake with the floor, creating compelling rhythms—rhythm in sound, rhythm in movement, and rhythm in line. How frustrating to have it end just as it was building up to some kind of answer. The vignette that followed cracked up the audience, though. The rhythm explored here was ballet photos: hit the pose, smile, flash of light from the camera, rest, repeat.

I know the projections in Tuplet were a key element, but for the most part I missed the point of them. Some of the images were of folks who were endearingly jovial in their creation of rhythm (band players, people laughing, etc.) but surely there was more to it. Just as I was getting really annoyed at how the projections upstaged the dancers, though, I found one projection that worked for me. The right screen showed a woman from the hands-up playing the piano and the left screen showed (her?) feet working the piano pedals: two hands, ten flying fingers, two sensible shoes—so many different rhythms from one person playing one song!

Some of the vignettes went over my head, too. Was there a rhythm to my understanding some and not understanding others? (Yes, I think so. My brain and heart were saying: got it, don’t get it, got it, got it, don’t get it, don’t get it, got it…”)

I think a second viewing would have clarified some vignettes for me. There were enough to enjoy on first viewing, however. One of my favorites incorporated the self-talk that dancers do—the onomatopoetic sounds they make or think as they’re memorizing a new piece. In Tuplet, we hear recordings of these intimate, individual rhythms as the dancers run the same dance phrase multiple times. In Bond’s solo, there’s an added punch line: each time he ends the phrase, he takes a moment to check where his feet are. That look down is yet one more rhythm, and I thank Professor Ekman for helping me to see/hear/feel that.

The third piece of the evening, Crystal Pite’s Grace Engine, was a huge disappointment to me. I’ve missed every single one of her much-acclaimed shows in Seattle (not on purpose) and so I was particularly eager to experience her work. This was the wrong one to start with. It was beautifully polished and specific, which I appreciate, but it reminded me of an improv class I watched last summer. This is not to say anything negative about improv classes. It’s just to say that when I touch your shoulder, you move your leg, the assignment is to stay connected and flowing, so now I’ll put my head in the arch of your foot, and then I’ll put my head in the arch of your knee doesn’t touch me. And do we really need so much crying and slow motion?

The interesting lighting and the cool subway rumble score and those gorgeous, intense dancers couldn’t help me over the hump with this piece. This, I thought at one point, is what happens when theater workshop and yoga take over the dance studio. Of course, I don’t know that for sure. I do know that at least one critic this year thought Grace Engine was the strongest piece of the night. That’s comfort for Pite, who perhaps is growing something important here. Comforting for me, though, is that my Crystal-Pite-fan friends assured me that her other work has a different feel. I hope to get to see that other work.

This was Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet’s first trip to Seattle. They’ll be 10 years old in 2013. I hope they come back so we can celebrate their anniversary. In the meantime, we have online videos and can glimpse the company on their home turf in the movie The Adjustment Bureau. I admire and appreciate Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet’s skill, flexibility, specificity, musicality, strength, and stamina. They have, as the Tuplet voice-over said when describing rhythm that works, “a sense of heart.”