Green Chair Dance Group‘s Tandem Biking and Other Dangerous Pastimes for Two ends the SCUBA 2013 program at Velocity Dance Center (through April 28; tickets) but as they are visitors to Seattle, let’s talk about them first. That way we can get right into how they quirkily talk the audience through an “inside look” at a three-person dance troupe and their interpersonal dynamics.

That the explanations are often unclear, gnomic, or non sequiturs takes nothing from the earnest helpfulness with which they share the names of various pieces (“We Are Reasonable People,” “We Are Luscious People,” “We Are Desperate People”), announce the rationale for their order (the favorite one comes first), or instruct the audience that the games they’ll be playing, however, are “real” (immediately undercut by Sarah Gladwin Camp letting everyone in on the fact that de Keijzer’s game is wearing natural fabrics: cotton, organic cotton; while she, Gladwin Camp likes to play “Don’t Touch My Face,” a game inspired by the fact that she doesn’t like water or people touching her face, and which is indicated by her making a shuffling gesture of disdain with her hands and fingers).

Early on, Gregory Holt gets so carried away with his narration that he mansplains another dancer out of existence, dropping to the floor to show everyone what her dance is like. Dance is decentralized here — or, looked at another way, made so diffuse it permeates everything. Though the work begins with a polished, in-unison phrase that they bring back (seasonally, in swim wear and snow gear) — kicking prettily from a beach-blanket pose, jacking through a turn on their backs by swiveling their hips, hopping to their feet for some stepping — there are also extended, aggressive capoeira-esque bouts, “monument” building where bodies are placed on or jointed into other bodies, and de Keijzer’s contorted face and tongue “dance.”

Gladwin Camp mentions, of a Holt-de Keijzer duet, that it was, for her, like looking through the wrong end of a pair of binoculars. The tension inherent in Tandem Biking for a three-person group gives it both cohesive and propulsive force. De Keijzer says that she’s pretty sure they could all three handle being cooped up in one small room for years, so long as, on a rotating basis, one could leave to have some time alone. The flip-side of that is when one watches as the other two perform. Gladwin Camp emerges bundled up like the kid from A Christmas Story, and it’s both a metaphor for a sort of bruised tenderness, and not a metaphor at all, but a wintertime reality.

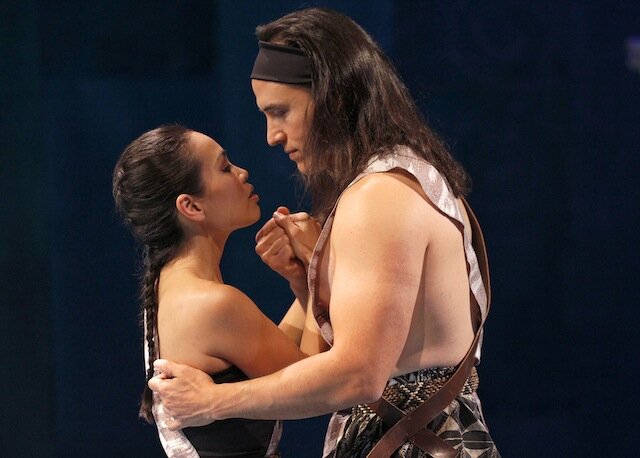

Maureen Whiting‘s About That Tree, with its painted-face dancers in tunics and pelts, seemingly living among or caught by the battered branches of a fallen tree, swiftly generates an atmosphere that, this particular year, might remind you of Rite of Spring‘s mythic primitivism. There’s not a lot of spring to be seen, though — the tree has fallen, and a bag of dusty, dead leaves is emptied onto the stage (costume and visual design are by Danii Blackwell and Jean Hicks). Music by Dave Abramson, Eyvind Kang, and Evan Schiller, in vastly different idioms, fits perfectly with the choreography for a 14-person ensemble.

When I saw an excerpt in rehearsal, Whiting was still determining if the “center would hold,” in terms of there being a focal point for the audience — 14 dancers is a lot to attend to. But she’s pulled it off without resorting to strict unison movement that might dampen the individuality expressed by her dancers. She uses breathing, and the sound of it, to move your attention; competing rhythms arise and generate a sort of group “breath” — or not. At one point, a dancer grabs the tree and holds a chunk aloft, another begins a solo with a sort of switch, another balances small branches on her shoulders, head, in the small of her back. The piece ends with a dancer, having grabbed the tree for herself, dropping it to let its clatter disrupt the breathy group communion.

This world premiere is a work you may want to see — and hear — a few times. There’s a poetic compression to it that leaves you wanting more.

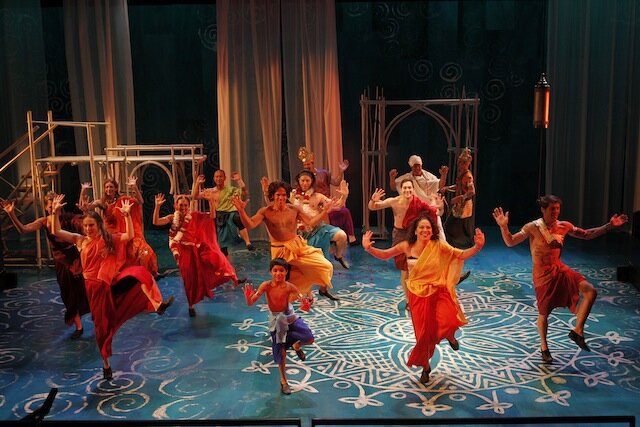

I had a similar feeling about the excerpt from Shannon Stewart‘s An Inner Place That Has No Place, which I saw an earlier version of a year ago. Here, what had been the last segment came first — dancers Meredith Horiuchi, Mary Margaret Moore, Aaron Swartzman, Rosa Vissers, and David Wolbrecht start off with a high-energy routine, complete with whoops of theoretic delight, that evokes a workout class’s slightly manic pace (music is by composer Jeff Huston).

Initially, the movements are both mechanically precise and slightly cliché, Broadway-musical-style, but then the dancers start shouting out icebreaker-style questions to each other about their pasts that get a litte intrusive (“Where did you lose your virginity?”) and as answers are given, the strict cohesion falters and they start interacting with each other with more idiosyncratic movement. But later, they’ll group around a single dancer and barrage him or her with questions, bumping up against, until the person seems to pass out, so it seems that perhaps moderation is key.

Behind the troupe, a striking video projection (courtesy filmmaker Adam Sekuler) shows them repeating into infinity — this later changes into an expanse of night sky that feels both beautiful and ominous, with a single dancer left. In a middle segment, the troupe poses for a series of memory-photographs, in ways that are both satirically funny (they look to be drunken party shots) and increasingly eerie, as the dancers’ expressions freeze into rictuses or slowly melt away. Even in excerpted form, the work packs a punch that you’re never quite ready for, as its set-ups veer off down unanticipated alleys.