In their U.S. debut—the only other stop their trip was the Joyce Theater in New York—Introdans made a terrific impression with its dancers Thursday night at UW’s Meany Theater (performances through May 12; tickets).

The Dutch company was founded in 1971 by Hans Focking and Tom Wiggers. Wiggers is still there and since 2005 has been general director, the same year another longtime company member, Roel Voorenholt, took over the role of artistic director. Since then there has been a huge turnover in the dancers. Only two were in the company before the directorships changed over, and the rest joined in 2008 or later. Their extraordinary caliber as a company seems all the more astonishing, given their current youth, relatively, as a group.

The company describes its programs as “thematically designed modern ballet,” and the balletic background is clear in performance, the training of the very best.

The program at Meany, titled Heavenly, included works of three choreographers: Nils Christe’s Fuenf Gedichte (Five Poems), Gisela Rocha’s Paradise?, and Ed Wubbe’s Messiah.

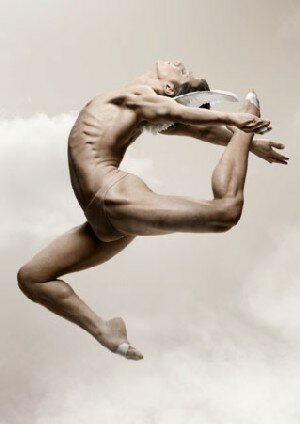

The highlight of the performance, Christe’s Fuenf Gedichte, presented a seamless connection between the music (Wagner’s Wesendonk Lieder with the ravishing voice of Jard van Nes), the projected backdrop (roiling clouds in a blue sky), the costumes (simple body-hugging leotards or tights in dark or jewel colors and, for one dancer, brief nude-colored shorts) and of course the movement.

The choreography celebrated the beautiful fluidity of the bodies.The five sections each flowed as poems should, across the stage and in each individual, while Christe created unexpected and unusual moves within a balletic language. These required enormous strength and stamina from all the dancers, in order to keep the fluid forward motion continuing.

The other two works were less successful choreographically, though both have had success in the Netherlands. Paradise?, which appeared at first glance to be a bunch of aimless kids showing off on a foggy night in the ‘hood, under rows of glare lights, continued too long without adequate structure, though there were moments of interest. One dancer sang her way through the group with a microphone before handing it over and dancing with the rest, and a fine tap dancer arrived toward the end. The music seemed as fragmented and aimless as the kids. Certainly not paradise, but perhaps that was the interrogative point.

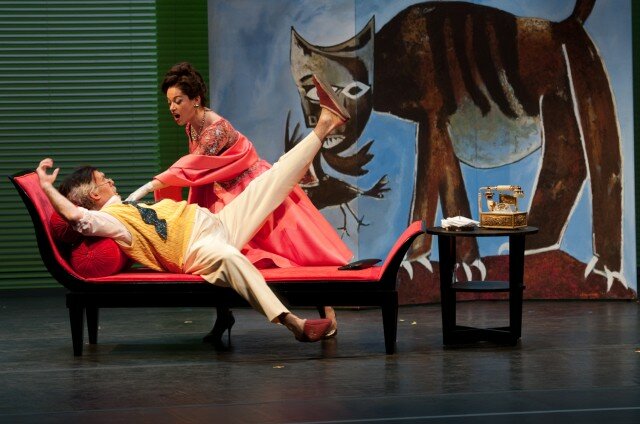

Wubbe’s Messiah, from 1988, felt a bit dated. The choreography, beautiful as the moves were, seemed conventional in comparison to Christe’s Gedichte, and the use of billowing, brilliant white skirts being swirled in huge figure-eights across the back gave one a distinct feel of Martha Graham. The rest danced in severe black. Somehow, the music from Messiah felt like a disconnect. There seemed no relevance in the dance to either words of great joy or great sorrow.

Yet, throughout the performance, the pleasure derived simply in watching these superb dancers overcame shortcomings in the choreography. I hope to see them return.