Last week, a 150-foot Japanese fishing boat (outfitted for squid-fishing, to be precise) was spotting drifting, unmanned, about 150 nautical miles off B.C.’s Queen Charlotte Islands, and its arrival raised, more urgently, the question of what is to be done about the bulk of the debris when it arrives. (“Bulk” in abstract sense; the ocean will have had the chance to break up the debris into smaller and smaller pieces, scientists think.) Because not much is being done.

As Canada’s National Post reports: “Although authorities expect the ship to make landfall in 50 days, all it would take is one storm to send the vessel crashing into the coast before the week’s end. Nevertheless, there are no plans to intercept the ship.”

Why? Because offshore salvage is difficult and expensive, and it’s not clear yet how much the boat is worth (though you have to respect a boat that can sail itself across the ocean with no hands, and remain right-side up). If and until it becomes a significant hazard to navigation, or it is clear where it will wash up, there will be more watching and waiting. This is the dilemma in a nutshell when it comes to the larger governmental response to tsunami debris coming ashore.

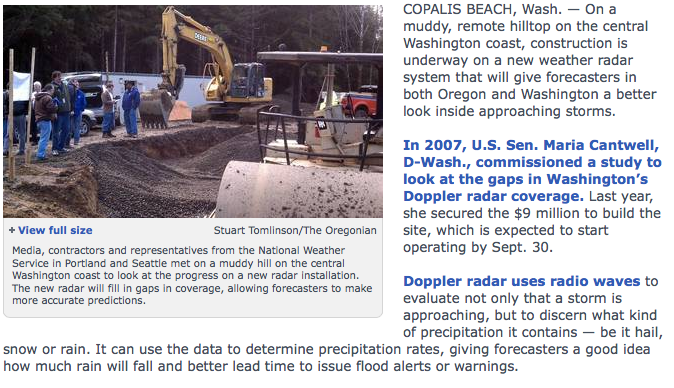

On the U.S. side, Washington State Senator Maria Cantwell has been urging the government to bite the tsunami-debris bullet and act:

This discovery is further proof that the U.S. government needs a comprehensive plan for coordination and response to the tsunami debris. Coastal residents need to know who is in charge of tsunami debris response – and we need clearer answers now. Hundreds of thousands of jobs in Washington state depend on our healthy marine ecosystems. We can’t afford to wait until more tsunami debris washes ashore to understand its potential impact on Washington state’s 10.8 billion dollar coastal economy.

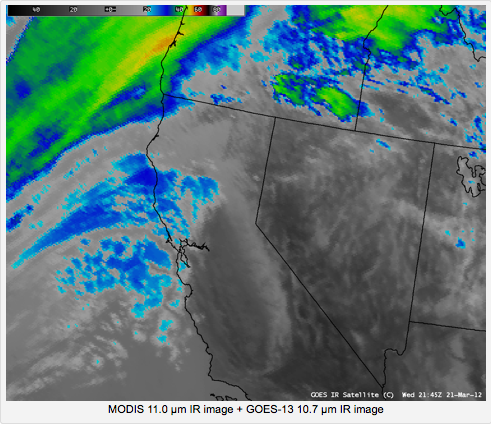

The March 2011 tsunami that hit Japan created an estimated 20 to 25 million tons of debris, a good deal of which was swept back into the ocean by the receding waters. Some of that sank, but some floated, and days later it could be seen in a huge debris field, heading out to deep ocean. After that, the debris dispersed enough so that it was no longer visible to satellite.

A year later, no one is sure precisely how much debris there is out there, whether or not it’s radioactive enough to worry about (unlikely), and what it will take to address the problem. In fine governmental form, the most common response seems to be to delay taking action as long as possible, in the hopes that it will become someone else’s problem. NOAA’s tsunami debris FAQ explains:

It’s hard to take emergency actions when there’s so little information about what we’re responding to – remember: it’s possible that most of the debris will break up, sink, or get caught up in existing garbage patches.

(Following on this, NOAA is also happy to explain to you why they’re not planning to do much about the garbage patches, either. Just in case you were going to ask.)

Perhaps not coincidentally, non-governmental estimates as to the arrival date of the debris have come with less runway. Ubiquitous oceanographer Curt Ebbesmeyer began reporting that the first wave of debris started showing up last October. On March 15, on his blog Beachcombers’ Alert, he wrote: “The identity of intermediate wind factor flotsam remains uncertain at this time. We suspect it will include overturned boats and the crowns of homes.” In a more recent Vancouver Sun interview, he mentioned that several more boats have been spotted already.