Thanks to the munificence of the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, I’ve been reading a report by the Helicon Collaborative, about arts leadership in the Pacific Northwest (pdf). Here’s what they wanted to know: Who was succeeding without being rich ha ha rich? As I read through the findings, and (see if you agree with me) I began to wonder if maybe the “declining arts audience” is a function of zero-sum arts marketing. Is the converse true? (The conversation continues on Helicon’s blog.)

Take the case of Anchorage Opera. Here is the “innovation” that caught my eye: “Whereas the opening night gala used to cost $500 a plate and attract fewer than 100 people, it is now a $25 party that welcomes all. Last year, 1,000 people attended, most of whom had never been in the building before.”

The other groundbreaking move? Musicals. Their audience didn’t see that there was a huge difference between musicals and opera, so Anchorage Opera decided to oblige them. Attendance is up 50 percent overall. Thank you profit-making South Pacific. (I know, I know–opera sucks at drawing crowds, you might argue, but it’s opera. CATS is not. Yet I don’t think Anchorage is pandering; I think they’re getting to know their audience, and are cultivating their interest in a range of music and theatre. As you’d hope, newcomers attend a musical, and feel emboldened to try out an opera. In a different niche, a different kind of programming.)

Closer to home, Seattle Art Museum, On the Boards, and ACT also get admiring close-ups. ACT deservedly gets a great deal of attention, thanks to its willingness to experiment not only with its programming but with its identity and organizational structure. I spoke with Gian-Carlo Scandiuzzi just about a year ago about ACT’s reinvention, and while that interview looks to be becoming an annual thing, it’s good to see other local leaders are heard from.

That said, it was ACT’s Kurt Beattie who supplied the key phrasing–a “vertical ecosystem of artistic practice”–that has guided ACT’s changes. Helicon notes that a clear animating purpose is foundational for high performance. (Most mission statements will have the high performance part just written in there, rather than describe precisely how and why that’s going to happen.)

I know you want the whole Helicon checklist for high-performing arts groups, so here goes: a) a clear purpose and compelling vision, b) deep community engagement, c) unblinkered evaluation and analysis, d) nimbleness and flexibility, and e) distributed leadership. That all sounds good, but you really need to soak up the examples provide to learn the underlying lesson, which is that this is only going to work if your organization is predisposed to evolutionary change (not many are), or if pressing environmental factors are giving you the leverage you need.

Well, in most cases these days, the environment is a friend to changing the status quo. I love the following quote from an article at Grantmaking in the Arts: “Please, Don’t Start a Theatre Company!” Everyone knows that Robert Frost poem, yes? So why is Rebecca Novick able to write this:

In the past fifteen years, the number of nonprofit theater companies in the United States has doubled while audiences and funding have shrunk. Neither the field nor the next generation of artists is served by this unexamined multiplication of companies based on the same old model.

It’s the road less traveled by that makes all the difference. Seattle’s theatre scene is not at all resistant to the kudzu of neophyte companies. We are loaded down to the leaf springs with acting talent, there’s a kaleidoscope of artistic directorial visions, but, sadly, operational collaboration lags behind. (I can’t criticize without mentioning the existence of Shunpike, an organization that’s been meeting a lot of these needs since 2001: turning artists into professional arts staff, providing fiscal sponsorship so you don’t have to 501(c)3, and even matching artists with venues. And let’s not forget Springboard, either.)

I am keeping my fingers crossed that the trio of Washington Ensemble Theatre, Strawberry Theatre Workshop, and New Century Theatre are having some substantive discussions about reorganizing as a tri-headed resident theatre in their new 12th Avenue arts space, but neither would I be surprised to hear that they’re just roommates.

This is the moment Helicon would likely recommend a ruthless self-inventory. ACT, Seattle Symphony, and Seattle Opera could certainly pass on some counterintuitive advice about expectations around new venues–almost nothing is more expensive than moving into and maintaining a new venue, and you will need to make dramatic changes to your business model to adapt.

Scandiuzzi likes to say budgeting is simple. Don’t spend more than you make. To ensure that, ACT now budgets for less than they made the preceding year. They can always make more money than they expected, after all. That’s great. But many non-profits like to follow a more “linear” last-year-plus-five-percent forecasting model, turning an Excel graph into a Magic 8-Ball.

On the Boards’ Lane Czaplinski calls it the “grow or die” metaphor, and it can be fatal. With the Great Recession coming on, OtB forecast a ten- to fifteen-percent drop in revenue, and then doubled it, just to be on the safe side. That’s ruthless, for a non-profit. There’s never any real fat, and what will people say? A few years later, as it turns out, OtB gets featured in a best-practices study. Compare and contrast with the former Intiman.

(If you’re going to cut, advises Helicon, don’t assume you know best for staff: Ask them to generate the best ways to cut costs, and offer them the chance to choose. Someone might like to take advantage of a month furlough during a slow period. Someone else might like a 4-day workweek better. That’s another lesson from ACT’s files.)

Seattle Art Museum’s plaudits come from its partnerships and community activities. It’s now apparent that if you are an arts organization with a building, and you aren’t throwing that space open to artistic and community partnerships, you’re making (Gob Bluth V.O.) “a huge mistake.” You may have a mission, and you may think that’s your focus, but what you have is a building, and the building weighs a lot more on your balance sheet than a mission statement.

SAM–besides throwing itself open to community celebrations of its exhibits–puts a tremendous amount of energy into artistic and cultural collaborations that speak to SAM’s idiosyncratic identity. A museum is a museum is a museum. But SAM is SAM. Only SAM is located where it is, has those particular rooms and halls, has its ability to welcome and showcase (to curate) Seattle’s arts and cultural scene.

This is a long way from: We exist to show you great paintings. SAM’s quarterly, late-night Remix parties have made it a for-reals, no-hype destination for people who never felt invited before. (You know how insecure hipsters are.)

If it is difficult to ask yourself, as an organization, if maybe the arts audience is just not that into you, it’s even harder to answer without excuses. Everyone can list ten reasons why people may not like the art being presented. As a professional, I can give you 25 really good ones that will fit most occasions, including climate change.

But SAM’s Sandra Jackson-Dumont makes a point about arts partnerships that is worth repeating in a wider sense: Arts organizations need to stop treating the arts audience as if they are scarce game.The bigger the organization and the larger their associated ticket price-point, the more they tend to fight for the well-moneyed-yet-cultured class. It’s just assumed that everyone is spoken for. Except when they’re not, as SAM’s success in drawing new audiences illustrates. Are they “museum-goers” (hushed, reverential, painting-watchers)? No. Are they Seattleites in search of cultural experience? Yes.

And also, there are weird proliferations of arts-group species that have nothing to do with public demand: As Novick mentions, every theatre group’s existence supposes an audience will support it, whether anyone asked for it or not. In Seattle, there’s also a profusion of chamber music groups that is disproportionate to the number of people who currently attend chamber music, or can define the term. But you can’t stop four musicians from forming a quartet.

So, a thought experiment, for groups big and small: What if everybody came? You probably have two immediate responses. First, that would never happen: Not everyone likes Schnittke. Secondly, that could never happen: Every organization is limited by its physical capacity.

What I want to emphasize is that zero-sum marketing (“This is our arts audience–you get yours!”) is born from an infantile, parasitic world view. “Infantile” because the priority is on having your needs met. Too many young organizations begin with a burning desire to state their mission, without taking into corresponding account the needs of the larger audience around them. “Parasitic” because they intend to subdivide the existing arts audience, rather than add new members to it. (I’m sure there’s a nicer way to say this.)

Helicon throws the word “evolutionary” around in their report, but let’s use it more rigorously. Consider the uproar over E.O. Wilson’s repositioning of social organization and how it creates “group selection” effects. All the way from Boston’s NPR station, a quick summary:

It turns out that the two dozen eusocial species became adept cooperators due to a combination of thousands of generations of genetic adaptations that led to the formation of nesting colonies. (Think ants, bees, wasps, the naked mole rat.) The tendency was cemented in human evolution when human ancestors came together in early tribes who hunted, foraged and lived cooperatively.

Only an arts community can ask, seriously, What if everybody came? That’s the kind of question that’s almost never asked by any single organization. It’s absurd. Can you imagine? But it is exactly the question an arts community can respond to (if not, precisely, ask) through its organization and behaviors.

You begin to see inklings of this wider consciousness in the behavior of Helicon’s “Bright Spots”–they are strongly adaptive to their particular community’s (not just “their audience’s”) needs and interests, and they shift roles depending upon their context in the arts ecology. Discovery of those needs can lead to significant role changes, not just in terms of “delivery of the product,” but in terms of what the desired artistic experience is.

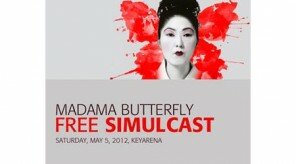

Adaptability can be thrust upon you. When Seattle Opera offers a free HD screening of Madama Butterfly in KeyArena, it’s big news. When times are good, McCaw Hall is selling out, and donors are flush, an opera company may not worry so much about playing to the same people, season after season, just a little grayer. So this is a bold populist move, from a functionally elitist art form. (“We’re a luxury good,” I was told once. “Like a Lexus.”) The Opera is still selling tickets to its shows, of course, and there’s no reason to assume every opera should be HD all the time. It’s a response. You make a change, you evaluate, you decide what to do next.

Adaptability can be thrust upon you. When Seattle Opera offers a free HD screening of Madama Butterfly in KeyArena, it’s big news. When times are good, McCaw Hall is selling out, and donors are flush, an opera company may not worry so much about playing to the same people, season after season, just a little grayer. So this is a bold populist move, from a functionally elitist art form. (“We’re a luxury good,” I was told once. “Like a Lexus.”) The Opera is still selling tickets to its shows, of course, and there’s no reason to assume every opera should be HD all the time. It’s a response. You make a change, you evaluate, you decide what to do next.

Is opera broadcast in HD still live opera? Is HD theatre still theatre? These are interesting, important questions. Are they more interesting and important than the pent-up demand for them? Is there a good reason not to realize the black box theatre space can function as a broadcast studio (with a “live studio audience”?)

Go on. Push yourself back from the spreadsheet. Ask yourself, What if everyone came?