Novelist Joshua Mohr talks with novelist Jonathan Evison at the University Book Store, on November 17, at 7 p.m.

Joshua Mohr is sort of a handful. His debut novel, Some Things That Meant the World to Me, has the title of a poetry chapbook, and the soul of one as well, though on the spectrum it’s more Bukowski than Wordsworth, as the the blurb from O, The Oprah Magazine, clarifies.

It’s hugely ambitious, in that Mohr wants to tell the story from the point of view of someone with dissociative identity disorder, and you probably do not want to listen to this person tell you about what exactly happened in their childhood. It’s against your better judgment that you keep turning pages, even as “Rhonda” makes staggeringly poor life choices.

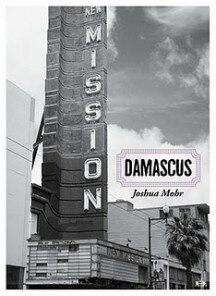

Mohr writes out the sordid heart of San Francisco–specifically, the Mission District–and if you’ve spent much time by the Bay, you’ll recognize that unsettling warm-sewer-whiff-in-the-street urbanity that permeates his books. It’s a radical empathy with, or even in preference for, the stinky side of life that, mostly unseen, underlies everything.

In Damascus, Mohr returns you to a down-and-outer Mission bar with the shards of twenty mirrors glued to its painted-black ceiling, “transforming Damascus into a planetarium for drunkards: dejected men and women stargazing from barstools.” In the first two pages you meet Owen, the bar’s owner, who has a Hitler-‘stache birthmark beneath his nose; Shambles, the patron saint of handjobs; and No Eyebrows, a middle-aged man dying of cancer and on the run from responsibility of any kind.

In Damascus, Mohr returns you to a down-and-outer Mission bar with the shards of twenty mirrors glued to its painted-black ceiling, “transforming Damascus into a planetarium for drunkards: dejected men and women stargazing from barstools.” In the first two pages you meet Owen, the bar’s owner, who has a Hitler-‘stache birthmark beneath his nose; Shambles, the patron saint of handjobs; and No Eyebrows, a middle-aged man dying of cancer and on the run from responsibility of any kind.

So far, so San Francisco. You simply have to make your peace with the fact that San Francisco’s human flotsam and jetsam (Rhonda makes a cameo appearance) is of a more captivating sort than many places–and with Mohr’s penchant for mixing ripped-from-the-journal reportage with prose poetry:

And other things were happening in the world, of course. Because there always are. There has to be. A couple who’d tried to conceive a child for years finally succeeded. A son estranged from his mother for almost twenty years picked up the phone and called and apologized for his role in their corrupted history. A seventeen-year-old girl’s cancer when into remission. Separated spouses decided to keep struggling through their knot of marital woes. A sunflower bloomed in Fargo, North Dakota. It rained in Orlando, Florida.

The book is bipolar, in that partly it tracks the unlikely, hermetic romance between no-strings Shambles and no-hope No Eyebrows, and partly it observes how the Iraq War intrudes into the Mission District of 2003–a performance art installation meant to honor dead soldiers (but featuring dead fish) attracts a more muscular critique than anticipated.

“Screw the critics,” Revv said, pushing the beers across the bar to them, then coming back around and planting himself. “You made real deal art so don’t worry whether any academic dimwits get it or not. Let them snicker at cartoons in The New Yorker. The joke’s on them.”

It’s not the academic dimwits who object, though, but returned-from-Iraq soldiers, hypersensitive to civilian slights to their honor. It doesn’t seem like it can end well, yet, again, you keep turning pages.

Mohr’s writing is appealing because it is raw and unfiltered, overheard on the street or from the next bar stool, but it can also seem merely unvarnished, with its joints showing. I’m of two minds about that artlessness, but there’s no denying the effect, that it conjures a reality that stains you with the underarm sweat of the Mission, and the naivete of 2003, when no one would have believed eight more years of war were in store.