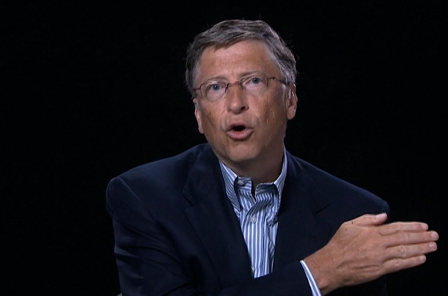

“I’m an optimist,” Bill Gates says, on the subject of nuclear power. “I see materials advances, simulations, better understanding of the scientific phenomena.”

Two things hold up innovation in the nuclear sector: First, the enormous lead-time it takes to research new technology and deploy it. And secondly, a global potpourri of regulations that can constrain innovative technology in favor of tried-and-true reactor design.

U.S. Deputy Secretary Daniel Poneman got Bill Gates on the video-chat line for the International Framework for Nuclear Energy Cooperation meeting in Warsaw, and the resulting interview is now posted on Gates Notes. The theme of the conversation is “Nuclear Energy after Fukushima,” and Gates finds two controversial lessons there.

While acknowledging that the Fukushima reactors’ failure post-earthquake-and-tsunami was a “tragedy,” Gates gingerly characterizes to the overall safety record of Fukushima as being commendable for a plant commissioned in 1971. This leads to his second point: that governmental regulation is biased toward the devil of known reactor design, rather than innovative solutions that take into account advances in software simulation (making it possible to assess virtual performance in a hurricane, earthquake, or tsunami).

“As I look at the energy sector I see that in some ways it’s more complicated than the IT sector where I spent most of my career,” says Gates. He lists the drawbacks of global regulatory complexity, the lead time before return on investment, the necessarily high bar for safety.

Though people may think of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as health-driven, its mission is to improve lives globally through innovation. As he considered the challenges the world’s poor face, says Gates, “I realized the very central role that energy plays in improving their livelihood. We need breakthroughs.”

His advice for governments? You’re under-funding investment in pure energy research by a factor of three or more. This wouldn’t require a gigantic tax on the energy sector, just a few percent, and certainly a lower number than a carbon tax would likely impose. Energy innovation is unlike other areas because of its lengthy time-to-market–if you try to offer incentives on the scale of other industries, you’ll fail.

“We need to have hundreds of companies trying out different things in each sector,” Gates argues, including solar, nuclear, wind, clean coal, and more. Cheap energy that doesn’t carry the greenhouse gas burden of today’s energy sources needs to come pretty quickly.

That preference for implementation seems to have established Gates’ primary bet on nuclear power (he namechecks TerraPower twice). “When you look at the numbers and you say, what could be significantly cheaper than what we have today, and located in every area, nuclear is one of the few that may be able to achieve that.”

He has invested in solar power, but is troubled by its disadvantages as a global solution: The “solar guys” still need to make solar power ten times as cheap, and solve storage and transmission challenges.

In nuclear, “I think you have to go for a big win, because you’re going to have your money tied up for decades.” It will be crucial to harmonize regulations globally, because you need a global market size to justify the size of private investment. Urges Gates: “We’re not gonna have a ton of nuclear start-ups, but we need more.”