Two hands meet and broach questions: Is masculine power inextricably woven into hip-hop? What is the role of the feminine in this worldwide cultural phenomenon? How does hip-hop meet queer? Kyle Abraham and his dance company, Abraham.In.Motion, are at On The Boards this weekend (through April 22, at 8 p.m.; tickets: $20) playing these questions to laughs, stopped breath, and more than a few plucked heartstrings.

Before those many meetings of hands the audience is prepped for a pop-culture encounter by pre-show club music that approaches nightclub volume. Once the dance begins, however, the sound mix is mostly arty electronica, though the moves range from popping to pointe work.

The dance quickly establishes Abraham’s concerns with a strong narrative of men finding tenderness and facing oppression and violence together. Hands meet for a suspended moment, the dance changes, relationships shift, and the community passes judgment. The narrative is reinforced by projections that both elaborate on and actually join in playing the danced scenes.

The performance takes its form from jazz’s correlated chorus—or more precisely Moby-Dick, though Stanley Crouch would suggest that it’s all the same, which is entirely appropriate. Abraham (the choreographer, not the Biblical Ishmael’s father) is chasing the elusive and the shape shifting. One scene demonstrates that hip-hop is very much a know-it-when-I-see-it affair only to be followed by dances that question what we know and what we’re seeing.

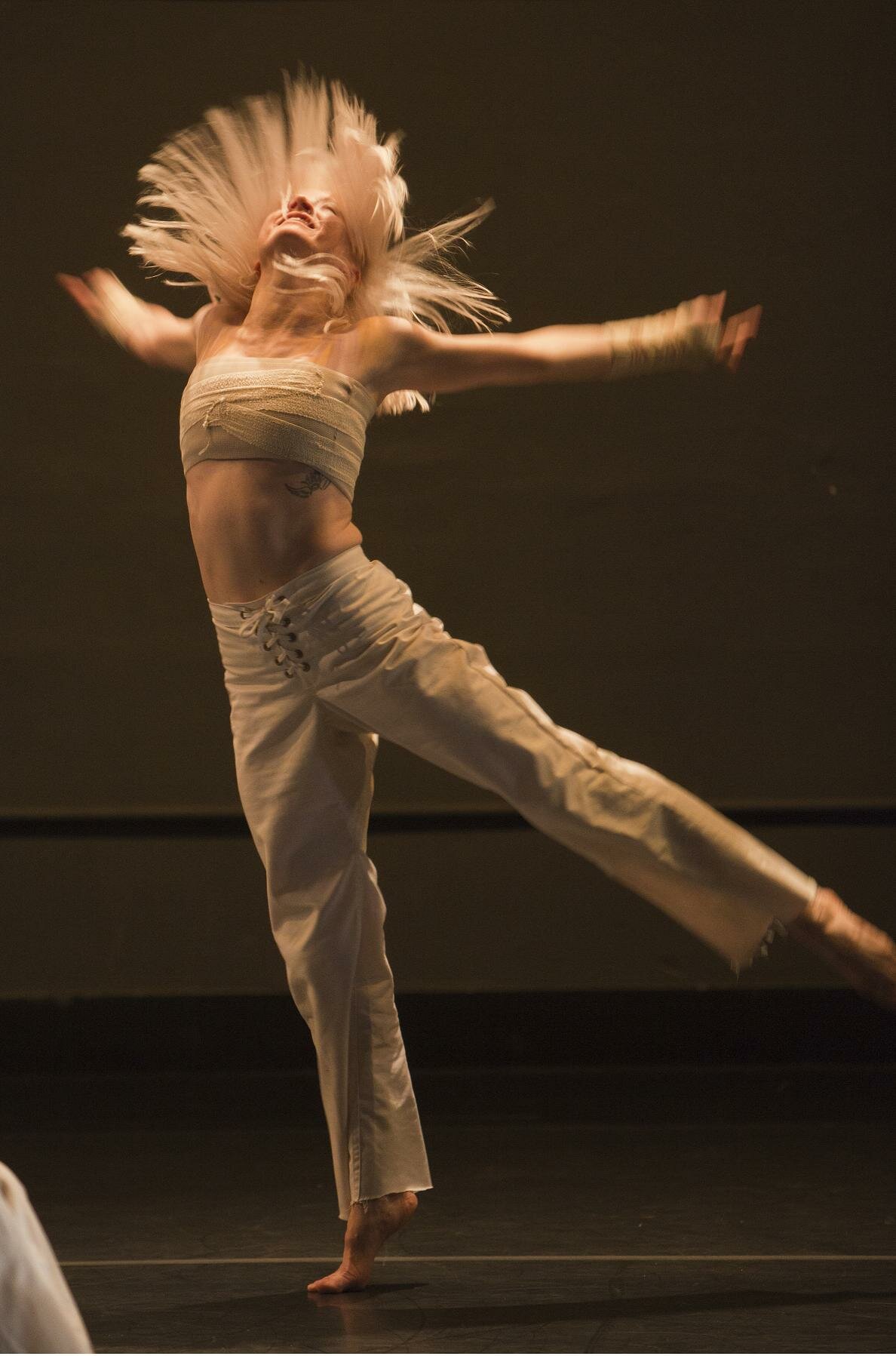

Where Melville alternates semi-scholarly cetacean treatises with the story of the Pequod, Abraham vacillates between declarative pieces dominated by male dancers and more abstract sections dominated by women. The chapters sail past with a surprise at every tack. Dan Scully’s lighting gets a lot of mileage out of a back curtain of vertical blinds. Language enters the mix and performs a duet with the choreography, asking those same questions with deeply committed acting.

Words bring laughter at the contrast between what is said and what is true and between the instruction given and the ways it may be followed. The words finally evolve into rap that Abraham delivers with such professional chops that a flub at Thursday night’s performance might have seemed planned if only the recovery had been repeated.

From electronica and rap Abraham and company eddy to a cover of Miles Davis’s Flamenco Sketches. The music leads the dance to one final moment of stunning grace. Could it be that Abraham has found peace with his whale?