The phenomenal production of Master Harold…and the boys at West of Lenin (through April 21; tickets) has all the trappings of a work from a much larger theatre. Catherine Cornell’s realist set, a recreation of the St. George’s Park Tea Room in Port Elizabeth, boasts worn, scarred linoleum, cookies under glass domes, a vintage jukebox, rotary wall phone. A sign in the hallway carries directions to the tea room, and to a pool. Producer AJ Epstein is responsible for many of the other elements that transport you into the moment: sounds of afternoon rainfall, the racheting of a phone being dialed.

As your eye rests on the linoleum you notice a faint, backwards “St. George’s Park Tea Room” in shadow, as if cast by light through a window. And then Kevin Warren (who’s popped up on Grimm on your TV) emerges, followed by G. Valmont Thomas (a name familiar both here and in Ashland) — they are Willie and Sam, the two black South Africans who work at the tea room. It’s 1950 and a long way from apartheid’s end.

Athol Fugard’s play was seemingly everywhere after its 1982 premiere, first as a challenge to apartheid, then as its obituary. To see it now is to be struck by how unerring Fugard is in finding the personal in racism’s sustenance (bitterness, shame, striving). Apartheid boycotts are not in the headlines, but South Africa is still peopled by those wounded by the shorthand of skin color for social class.

Fugard’s great pivot was, with Sam, to illustrate reverse compassion. We quickly see he’s a stand-in father for his nominal “boss” Hally (James Lindsay), who’s minding the tea room while his mother is at the hospital. Hally has long been Sam’s charge, and the course of the play is a retracing of that intertwined history — from Hally’s reminiscences gilded with casual, patronizing racism (and Sam’s teasing recollections of how Hally was forever underfoot) to Hally’s vicious attempts, as he loses his own footing, to remind Sam of “his place.”

All three are thoroughly coached in how to sound South African (Judith Shahn’s vocal work). Lindsay, in his schoolboy’s blazer (Anastasia Armes’ costumes are pitch-perfect), has the beleaguered look — and outlook — of an older man, who feels the world conspiring against his security. Brashly collegiate and lordly at the outset, complimenting himself on “educating” Sam time and again, he spirals into a rage that threatens to consume him.

Unseen is a homemade kite Sam and Hally once flew. It tugged at the end of the string, remembers Hally, like something alive that wanted to get free. It’s a resonant image, in the context of apartheid, but it applies to Hally as well, who would like to leave his younger self far behind.

Rage is also Willie’s problem — Kevin Warren bubbles over with fury at his absent dance partner (absent because beaten, as Sam points out). A dance competition becomes, in Fugard’s hands, a wicked analogy of perspectives on Western and “primitive” art and culture, as well as a metaphor on the ideal of shared political space in which everyone has been practicing their steps.

It’s also a way of delineating the way cultures can be blind to each other’s most precious dreams — Sam wants to know if a dancer gets demerits for tripping, which astonishes Sam and Willie as something unthinkable. These are finalists; they will be perfect. Sam coaches Willie on the quick-step (Warren with tense, seized-up joints initially, shoulders hoisted), and gradually he improves. (Actual dance coach Tina LaPadula can feel justifiably proud of their graceful twosome at the play’s close.)

Under the direction of M. Burke Walker, the trio of actors substantiate their shared history with an visible familiarity that’s hard come by on the stage. Walker knows he’s building to an explosion, so nothing rushes past; the pace is determined by the work being done (or ignored), stories being told, secrets revealed. It’s captivating.

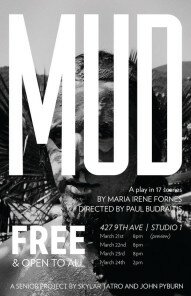

Mud, by Cuban-American playwright Maria Irene Fornés, came and went with great intensity last weekend. The New Yorker, while noting her tendency to set up shop at the intersection of poverty and feminism, said also that “her work sits in the ear like luxurious reason.” In Mud, characters Mae and Lloyd chant a plainsong of miscommunication, as Mae seeks to educate herself. Maybe the repetition is simply because they know the other isn’t hearing them, or maybe they still hope that a change in intonation will help them break through.

A senior project from Cornish students Skylar Tatro (who plays Mae) and John Pyburn (Lloyd), it was understandably austere. Paul Budraitis, who also directed, provided the set and lighting design, which for the most part consisted of a table and chairs, lit by a single overhead bulb. The costume design by Adam Hulse seemed to aim for a raggedly Appalachian feel.

As the play opened, Mae stood off to the side, ironing, while arguing with Lloyd over her schooling and their sex life. Lloyd, it transpired, was impotent as a result of an infection. But of course he couldn’t admit that — trying to shame and blame Mae, he told her he’d gotten it up with one of their pigs recently. Mae was unimpressed. She was more taken with the older Henry (Lantz Wagner, not looking a gift horse in the mouth), booting Lloyd out, and moving Henry in. Lloyd, like a kind of camp-robbing bird, skulked around thereafter.

It’s a difficult but rewarding play for young actors. What’s it like to be illiterate, for instance? Pyburn, rangy, resentful, restless, seemed to fade out of focus when it came to maintaining particularities of his character while Henry and Mae mooned over each other. Tatro’s Mae, sounding lightly down-home, seemed to find more to say in Fornés’ variations, and she’s adept at using her face as a mask — her forehead furrows, her eyes glisten, her lips tauten.

Budraitis, after showing us the table for most of the play’s hour-long running time, had one more directorial jab in store. Downstage, lit only briefly in flashes, were two rectangular planter-like enclosures, one filled with round rocks, another with dark earth. Henry would slip on the rocks, in a spasmodic, high-kneed choreography that seemed to catch him in just that moment of in-betweenness; and Mae would fall into that dirt, her blood turning it muddy.