The Seattle Symphony performs works by French composers Dutilleux, Dukas, and Ravel on Saturday, April 21 at 8 p.m. at Benaroya Hall. Also on the program is a U.S. premiere by Macedonian composer Damir Imeri. Featured performers are guest conductor Susanna Mälkki and pianist Simon Trpčeski.

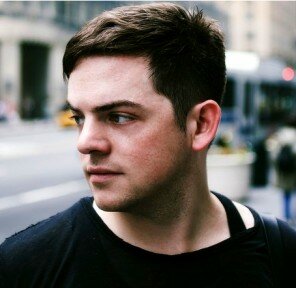

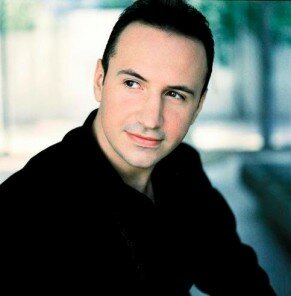

Benaroya Hall was full of international flair on Thursday evening. Seattle Symphony presented a program of French music, including Paul Dukas’ beloved work The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. On the podium was Finnish guest conductor Susanna Mälkki, a former professional cellist who is the first woman to conduct a production at Milan’s famed La Scala opera house. Brilliant pianist Simon Trpčeski, a perennial Seattle favorite, joined the orchestra for Ravel’s Piano Concerto and the U.S. premiere of a work based on folk tunes from Trpceski’s native Macedonia.

Henri Dutilleux’s Symphony No. 1 started off the program. Composed in 1951, this evocative work paired well with the cinematic flavor of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. The Seattle Symphony has featured several of Dutilleux’s works in the programs this season — a crash-course in the music of this 96-year-old French composer. Dutilleux’s Symphony No. 1 is colorful, exciting, and appealing to a wide range of audiences. It’s vivid orchestral music that paints a picture and tells a story. Each of the four movements could have been the mini-soundtrack to a short film.

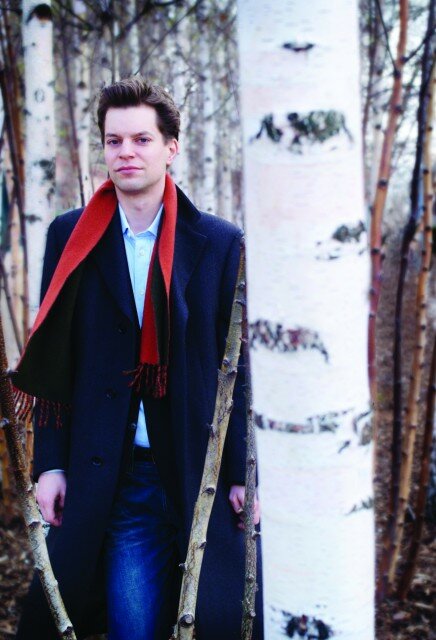

Following the Dutilleux, Trpčeski took the stage to introduce “Fantasy on Two Folk Tunes”, a piece for piano and orchestra by Damir Imeri, a young Bosnian-Macedonian composer. Written just last year and dedicated to Trpčeski, this work incorporates the melodies of two traditional Macedonian folk songs. Reminiscent of the music of Béla Bartók, who also used folk tunes in his compositions, Imeri’s piece blends traditional melodies and rhythms with a contemporary orchestral sound. Despite the occasional schmaltzy moment in the string section, the work was a skillful weaving of piano virtuosity with orchestral color.

Full of smiles and boyish energy, Trpčeski returned to the stage for Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major, diving into the playful first movement with enthusiasm. The orchestra responded energetically with outstanding section and solo playing, including the jazziest bassoon I’ve ever heard, courtesy of principal Seth Krimsky. The contemplative second movement occasionally lagged in energy, but Trpčeski perked right up for the speedy final movement, creating a sparking tone even in the most rapid and difficult passages.

The evening concluded with Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a work that was catapulted into fame by the Walt Disney film Fantasia. For many, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice immediately conjures up images of Mickey Mouse as the hapless apprentice, conjuring up walking broomsticks that quickly get out of hand. Although it’s now a pop culture icon, Dukas’ piece is dramatic and whimsical in its own right. Conductor Mälkki led the orchestra with clarity and vigor in a performance that was both powerful and fun to experience.