Last week, Wonkblog’s Brad Plumer delved into the myth of the “money-losing” Amtrak passenger train service, raising the notion that passenger rail could be profitable. (Like airlines? Peruse this list of airline bankruptcies carefully.) Business Insider picked up the profitable-Amtrak story, too. But both tend to skip over how the most profitable line in Amtrak history got that way.

Chronic operating deficits have plagued Amtrak since its inception. Even today, as it carries record numbers of passengers, Congress directly subsidizes the service. In 2011, that amounted to $1.4 billion against total revenue of $2.7 billion. (Besides Big Bird, former Presidential candidate Mitt Romney wanted to eliminate Amtrak’s federal subsidy as well.) Terrible spendthrift Amtrak, you’ve heard for decades, they can’t even make a profit on concessions.

Yet Amtrak doesn’t look much different from King County Metro when it comes to the struggle to meet operating costs while being directed to serve the greatest number of people, per geographic equity. That operating deficit is no accident, it’s baked in, just as it is with public transit agencies. And just as with public transit and public education, government has shifted costs elsewhere: In 1980, fares and other revenues met 42 percent of Amtrak’s operating costs. Per its 2011 annual report, Amtrak covered 85 percent of the cost of its operation, with the federal government still balking at 15 percent.

So where does the money go? Plumer refers you to a study by the Brookings Institution, which zeroes in on one likely culprit: “Amtrak’s 15 long-haul routes over 750 miles.” Congress, like the American people they represent, love services but not paying for them:

Many of these were originally put in place mainly to placate members of Congress all over the country, and they span dozens of states. This includes the California Zephyr route, which runs from Chicago to California and gets just 376,000 riders a year. All told, these routes lost $597.3 million in 2012.

This New York Times story, “How to Spend 47 Hours on a Train and Not Go Crazy,” gives you some idea of both the snail’s pace (relatively speaking) of cross-country train travel, and of the people served by Amtrak’s long-hauls (a large number of senior citizens and people with disabilities, says Amtrak, solidifying the public transit analogy).

In contrast, routes under 400 miles between major cities, argues Brookings, tend to pencil out nicely. You can see it in the numbers: 83 percent of Amtrak’s more than 31 million in ridership comes from these routes. Not all break even, but thanks to the extraordinary success of a few — the Acela and Northeast Regional routes now make a profit of $205 million — operating costs for this segment of Amtrak trips are covered and then some.

Using this calculation, in 2011, the less-than-400-mile routes made a profit of $47 million, while the greater-thans “lost” $614 million. (“Lost,” to emphasize that a national passenger rail network serving the bulk of the country will have varying costs. These are what they are — the question is whether the value of those long-haul trips is worth $614 million. Even The Economist admits that’s worthy of discussion.)

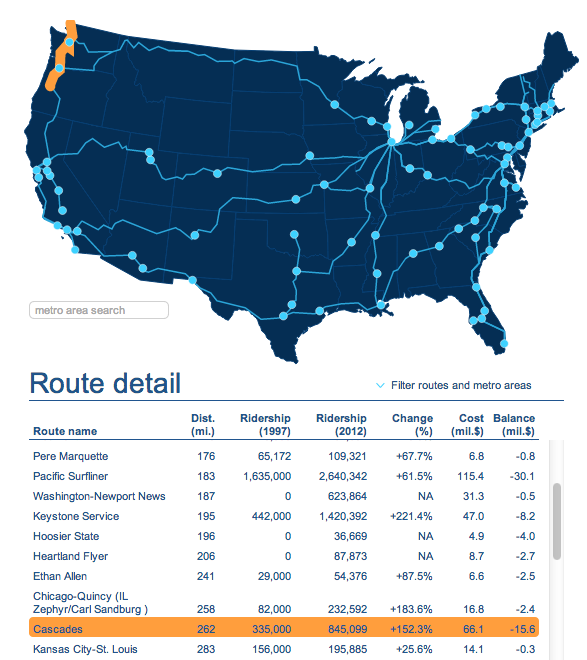

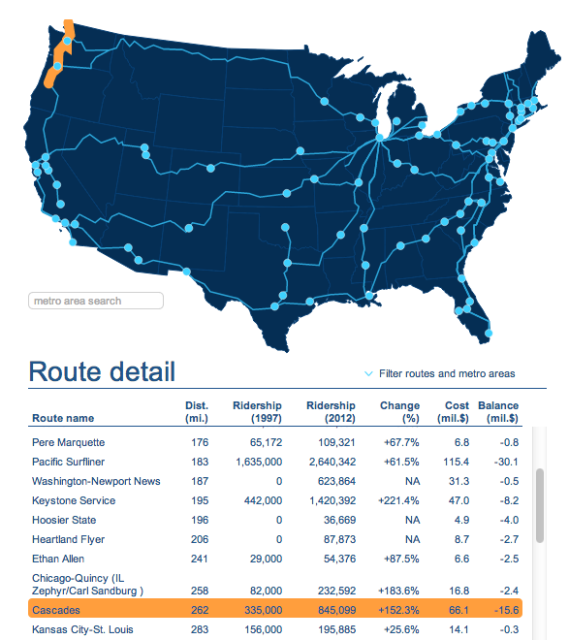

Using the Brookings interactive infographic on Amtrak route ridership, you can see that the Amtrak Cascades route has seen immense growth in ridership, more than 150 percent between 1997 and 2012. It’s subsidized by the states of Oregon and Washington. Still, it runs at a deficit, with its revenues amounting to 85 percent of the total. (You’ll also notice that there doesn’t seem to be a strict correlation between route length, ridership, and the cost of running it — the Chicago-St. Louis route is longer, carries fewer passengers, and manages a shortfall of just four percent.) Could it become profitable?

The answer to that seems a clear yes — but with a significant caveat to the Brookings findings. The idea of trip-length-dependent costs is likely to delight urbanists, in that they seem to illustrate the efficiency of urban densities. Outside of the Northeast, other high-performing routes are California’s Capitol Corridor and San Joaquin Service. Or they would seem high-performing, if there weren’t such a thing as the Northeast Corridor (NEC).

On the NEC, the Acela Express carries about half the total passengers of the Northeast Regional (almost 4 million to NR’s 8 million), but it brings in about 25 percent of total revenue. Its profit margins are on a different planet. Though its average speed is less than half its top speed of 150 mph, it’s still managed to corral around half of all the air and rail travel market in New York, Boston, and DC, between those destinations. Add in the profitable Northeast Regional, which can travel up to 125 mph on the NEC, and you have a more nuanced story.

It’s true that shorter runs come closer to breaking even, but operating profits come from high-speed rail. That’s what the two most successful Amtrak routes have in common: They travel on NEC track that Amtrak owns and maintains, currently the only high-speed passenger rail track in the U.S. That’s important because it upends the notion that a trip length of 400 miles is the primary limiting factor. The tracks, and who owns them, are, because that determines both maximum mph ratings and real-world reliability.

Creating a high-speed rail line out of the NEC was and is expensive (and comparisons that don’t take the associated capital costs into account aren’t simply unfair, they’re misleading). Amtrak as a network absorbed the costs of implementing NEC high-speed rail by cutting service elsewhere, especially on long-haul routes. It now has plans for true high-speed rail (achieving more than 200 mph) along the corridor, but estimates range between $120 billion and $150 billion.

The Amtrak Cascades route, on the other hand, is leased from freight carrier BNSF, which has never had any need for high-speed rail. Though the Cascades’s Talgo-trainset can handle a top speed of 124 mph by tilting into curves, because of track conditions, Amtrak is not allowed to exceed 79 mph. BNSF also restricts Amtrak’s usage of the railway both logistically (Amtrak can only run so many trains per day) and functionally (slow-moving freight trains are a top factor in Amtrak delays).

A planned “high-speed” upgrade for the route should raise the top speed to 110 mph (or 15 mph less than the top intercity speed on the NEC), and cut travel time from Seattle to Portland to two-and-a-half hours. That might be just fast enough to bring Amtrak Cascades into the black — but the route will still be dogged by slow freight trains, the fight to fit more trains into the schedule (the route already sells out in advance around holidays), and mudslides.

Congressional critics of Amtrak, you might be surprised to learn, seem most exercised about the direct subsidy to Amtrak, rather than the benefits-to-costs ratio of a national rail network. Indirect subsidy — funneling federal transportation money to states who might then decide to spend it on rail — enjoys more support, especially as states are taking up the responsibility of funding rail on their own. The Brookings Institution’s vision of an optimized Amtrak feeds that dream of limited, intercity travel, funded by states from their transportation coffers.

But it doesn’t emphasize nearly enough the relationship of high-speed rail to operating profits — and whether, with those costs amortized, the high-speed routes we have look nearly as efficient. It would be ironic if, in the quest for efficiency, Amtrak was robbed of the ability to invest in the one thing that’s proven to move its numbers into the black.