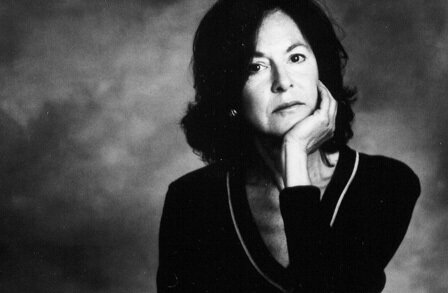

Poet Louise Glück speaks at Seattle Arts and Lectures this Thursday (7:30 p.m., Benaroya Hall), followed by a SAL visit from Alain de Boton on Friday (7:30 p.m., University of Washington’s Meany Hall), thus giving rise to this post’s headline, and a sense that I have accomplished, there, all I can in this life. Après cela, j’expire. (Obviously, I mean, one has to breathe.)

Either of these evenings will, no doubt, astonish and delight, and it’s a bit staggering to have them back to back. Louise Glück is one of our few first-rank poets, here in the U.S., someone who steadily fashions from life experience poetry, and yet resists the impulse to attempt to find poetry in everything: “I go through periods—long periods—of not writing.” If you approach poetry as a blind taste-test, hers are the ones you read and glance back up to the top to see who wrote them, because that is someone you want to hear from again. (A Village Life is her eleventh collection.)

Listen to her read “The Wild Iris,” the cadence and resonances, the way the syllables emanate from the mouth’s cavity with an almost impersonal agency. Formalism has different uses, but one that Glück puts it to is Procrustean (or yogic): to stretch the self to fit the space, so it just hangs there, almost naturally.

You want to keep that apparent ease in mind when, for instance, you read in “Persephone the Wanderer“:

You are allowed to like

no one, you know. The characters

are not people.

They are aspects of a dilemma or conflict.

Glück’s classical approach is modified by that contemporary consciousness; and if the mythic themes she explores roost in someone’s mind, someone’s body, it’s a mistake to imagine them confessional. It’s a question of emphasis. When young, you think the gods are present, distinct, kinetic; later, the same myth reads absent, diffuse, fiber optic. “The sun burns its way through, / like the mind defeating stupidity,” as Glück puts it. Glück will defeat your naive attachments.

And then there’s Alain de Boton, the patron secular saint of an over-educated, bookish, ruminative place like Seattle. His new book, Religion for Atheists: A Non-believer’s Guide to the Uses of Religion, makes the incontestable point that Dawkins, et al, frequently elide: It’s not because of its superstitions that religion endures (the supernatural claims of religions are constantly evolving to keep pace with what people are likely to believe, or not), but because its many social goods.

And then there’s Alain de Boton, the patron secular saint of an over-educated, bookish, ruminative place like Seattle. His new book, Religion for Atheists: A Non-believer’s Guide to the Uses of Religion, makes the incontestable point that Dawkins, et al, frequently elide: It’s not because of its superstitions that religion endures (the supernatural claims of religions are constantly evolving to keep pace with what people are likely to believe, or not), but because its many social goods.

On his site, de Boton or his copywriter asks if religion sans the supernatural can’t still show us the way to:

- build a sense of community

- make our relationships last

- overcome feelings of envy and inadequacy

- escape the twenty-four hour media

- go travelling

- get more out of art, architecture and music

- create new businesses designed to address our emotional needs

Having yet to read the book, I can’t tell you how persuasive his case is. It’s not that no one has pursued this path before. You could argue that Unitarian Universalists represent a sort of pilot project for getting people to come together in ethical community without the glue of sharply defined belief in a powerful sky god. You could also argue that Unitarians (and de Boton’s self-help-y list) represent a contemporary, denatured approach to a sense of the divine as an active force in life, something that transcends ordinary time. But I have always found de Boton books to contain deeper thinking than the title might imply.