The official opening of the Wallingford Greenway, Seattle’s first, is this Saturday, June 16, at 5 p.m. The City Council’s Sally Bagshaw, a big greenways booster; SDOT Director Peter Hahn; and friends of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways will be there for a ribbon-cutting ceremony (at North 44th Street at Corliss) allowing Kidical Mass—pretty much what it sounds like—to pass through.

We’ve discussed the family-friendly residential streets movement before: “It changes the whole personality of the street when it’s safe enough for kids to bike on.” Wallingford’s Greenway gets high marks in that regard because it connects younger cyclists to Wallingford Center, Wallingford Playfield, Hamilton International School, and school programs in the Lincoln High School building–all on a much quieter route than the larger arterial, North 45th Street.

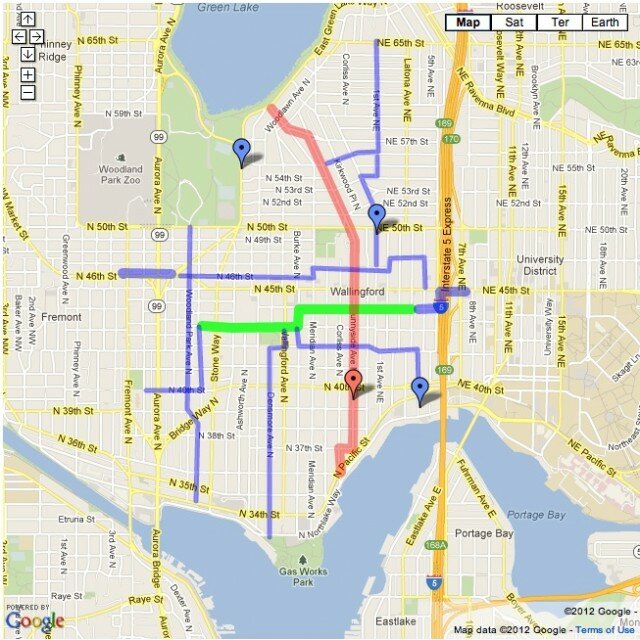

The completed section runs from North 44th Street and Latona Avenue NE to North 43rd Street and Stone Way. Signs marking the jog from 44th to 43rd are easy enough to spot.

SDOT sums up the work they’ve done (in 2012, they hope to install over eight miles of neighborhood Greenways in Ballard, Beacon Hill, Delridge, Wallingford and Ravenna/Bryant):

Traffic calming improvements include adding a green bike box(es) at 43rd/Wallingford, 44th/Latona, and 44th/Thackery; constructing a median at 43rd and Stone Way; adding on-street parking and installing signs to reinforce existing parking restrictions; as well as the addition of new directional signs and pavement markings.

On the other hand, you can see that this is a project that cash-strapped SDOT is trying to get done on the cheap. There haven’t been any significant reconfigurations of traffic–the route was no doubt chosen because it already included islands at the intersections, and SDOT hasn’t added any further traffic calming devices.

This is a thinner street than a boulevard, and with parking on both sides, bicyclists and cars proceeding the opposite direction will come head to head. (Parking on both sides also increases the chances of getting “doored” as a driver or car passenger flings one open in a cyclist’s path. SDOT actually added on-street parking, to appease residents.)

In a more perfect world, this street might be configured as one-way, and local-access only, with cars guided onto adjacent streets at each intersection, and only bikers and pedestrians allowed to use it as a thoroughfare. You’d want to see more substantive bike tracks–visible at a greater distance to cars–where it crosses busy streets. And on-street parking would be moved to pocket off-street lots, to create more room. It’s a start, though, and I’ll be interested to see if residents reclaim the street, as people have in Portland. Here are some visuals of how they’re doing greenways down south.