With this post, The SunBreak welcomes classical music reviewer Philippa Kiraly, who comes to us from The Gathering Note where she covered classical music the last three years, and before that, from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

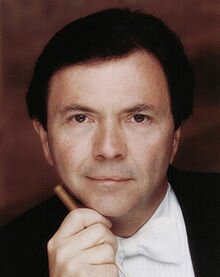

After 26 years at the musical helm of the Seattle Symphony, music director and conductor Gerard Schwarz steps down in a few weeks. His two concerts this month include the final works from the Gund-Simonyi Farewell Commissions, yet another commission by a group of donors, and Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony as his actual last directoral presence on the podium (on June 16; tickets).

Thursday night he shared his penultimate farewell concert, recognizing a couple of the musicians who are also leaving the orchestra: bass player Ronald Simon, with 50 years there under his belt, and principal flute Scott Goff, who graced the orchestra for 42 years in that position. The third, concertmaster Maria Larionoff, was sick and not present, but she will surely receive her plaudits at the next concert.

Friday’s concert was well attended, another plus for Schwarz who has been an excellent programmer over the years and inveigled many who thought they would prefer only old musical warhorses to come to concerts of new or unexpected music.

Two world premieres started it off. Paul Schoenfield’s “Freilach” is one of the Gund- Simonyi Farewell Commissions, and as he said in the notes, “Freilach” in Hebrew means “joyous and sometimes a frenetic style of music,” which he felt was a fitting return for “Jerry’s warmth, kindness and encouragement over the years.”

It was short, just under five minutes, but “Freilach” described it exactly. Modern in idiom, the music bubbled exuberantly, downright sassy in places, with a distinct Middle Eastern feel to the scale at times and often hummable melodies coming through. One could almost feel high kicks coming on, maybe today’s answer to the cancan. The big orchestra played with verve and light-hearted spirit.

Immediately following came another commission, by composer-in-residence Samuel Jones. After 14 years in that position, Jones is also retiring—to give, he says, the new conductor, Ludovic Morlot, the opportunity to make his own choices. We are fortunate to have had a composer the quality of Jones here for that space of time. His new work, which had the stipulation that it celebrate the special relationship between fathers and daughters, is somewhat of a hybrid, being part-tone poem, part-song cycle without words.

Titled “Reflections: Songs of Fathers and Daughters,” it’s more tonal that the Schoenfield, and also filled with hummable moments. It describes, though not implicitly, the life stages of a daughter from inception to falling in love as an adult, so there are many changing moods, sometimes a hint of tunes which just might have come from the Gershwin era, a pop waltz, school-type songs, a tad of Coplandesque harmony, some cacophony—when did raising a daughter not include some of that?, but all of it subtly incorporated in a satisfactory 20-minute work which held together and held the interest. An excellent performance garnered an ovation for Jones himself as well as the orchestra.

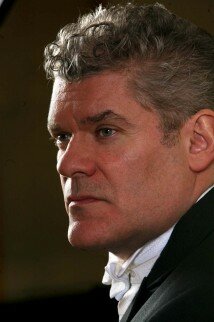

William Wolfram and Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 2 provided a change of pace to the 19th century. Pianist Wolfram is familiar to many Seattleites as a consummate chamber music player with Seattle Chamber Music Summer Festival, and he will be here the end of next month for that.

Friday’s was a stellar performance. So often, the number of notes in the piano role of a Liszt concerto seems to persuade performers that they should be glittering torrents of glissades, runs, arpeggios, and the like, more technical show off than musical interpretation.

Wolfram brought thought, care, and introspection to his playing. All the notes were there, clear and sweet, but he often seemed just to be caressing the piano keys, stroking the notes out with relaxed fingers, allowing the musical ideas to come through in shaped phrases and coherent progression. There was fire where it needed to be and the orchestra stayed closely with him not overwhelming his quieter tones, while acting principal cello Eric Gaenslen shared a long, singing duet with Wolfram. A lovely performance, a pleasure to hear.

I wish I could say the same of the Shostakovich Tenth Symphony which ended the program. It was a big work to end a performance which had required a lot of attention already, close to an hour in length and making an overlong concert. It’s a great piece, worth hearing when fresh, and the wind players particularly shone, including notable work from several principals: bassoon Seth Krimsky, horn John Cerminaro, clarinet Laura DeLuca, flute Scott Goff, and oboe Ben Hausmann.

However, Schwarz fell back into a habit he has gathered this past year, of trying to make every double forte a quadruple or even quintuple forte, forcing the musicians and making this listener (in Row N downstairs) feel like cringing back from the volume. This blare of sound detracts from the nuances of the harmonies which cannot be elicited from instruments when playing at that decibel level, and which anyway cannot be heard in detail in the din. Shostakovich was a master of orchestration and tonal detail, and it’s a shame for them not to be made clear.