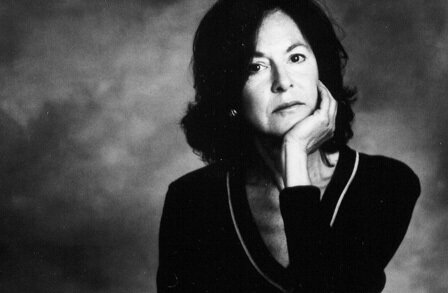

Part of Seattle Arts and Lectures series, Flynn’s talk summarized a lot of her writing career and the evolution from her novels Sharp Objects, Dark Places, and the breakout hit Gone Girl. It was full of great one-liners that I had to write down to tweet later:

"[My dad said] let's watch _Psycho_, it's time for you to learn about Hitchcock; you're almost six." #SALFlynn

— Chris Burlingame (@chrisburlingame) April 18, 2014

"When I was 12, I got a copy of _In Cold Blood_. I was almost a woman, it was time." #SALFlynn

— Chris Burlingame (@chrisburlingame) April 18, 2014

"There's this internet rumor that I wildly changed things [in the script to _Gone Girl_], that it's a musical now." #SALFlynn

— Chris Burlingame (@chrisburlingame) April 18, 2014

But the first thing she said was that she wanted to answer the question she most frequently gets, which is “What is wrong with you?” That seems like an even more dismissive and sexist way of the question Joyce Carol Oates so eloquently addressed in 1981 when she addressed the question “Why is Your Writing So Violent?” head-on in the New York Times. (Spoiler: it was about gender then and it’s about gender now.)

On a related tangent, when I saw Alissa Nutting speak on a panel at AWP earlier this year, she told a story of how she, who teaches creative writing and English at John Carroll University (outside of Cleveland), had the father of a high school student ask another professor why she was allowed near students because he read about the plot of her (quite good) novel Tampa. I know of no examples where male authors are asked to justify their imaginations to strangers in such a point-blank and condescending manner.

But to get back on track, if you get the chance to meet Gillian Flynn and ask her, even in that pretend-joking way, “What is wrong with you?” you are a bad human being who should be ashamed of yourself.

Flynn talked about her father showing her Hitchcock’s Psycho when she was six, saying, “It’s about time you learned about Hitchcock” and how she had gotten a copy of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood at twelve. “I was almost a woman now, it’s time,” she said (in case my tweets aren’t embedding above). It was comforting knowing that we found the same movies and books transformative, though I was a teenager when I discovered them both.

Flynn spoke at length about how she made the character of Nick Flynn resemble her own life as a writer who had gotten laid off at Entertainment Weekly. She said that the (Amazing) Amy character was meant to be someone who came into enormous privilege without really earning it. She also said that when she was let go at EW, she felt a lot of pressure to finish Gone Girl because she became, by default, a full-time novelist.

The ending of Gone Girl was sort of the elephant in the room, and mentioned several times without giving away the plot. A surprisingly large number of hands (maybe a dozen?) went up when interviewer (and author of the hilarious novel Where’d You Go, Bernadette?) Maria Semple asked the audience who hadn’t yet read the book. I would have assumed people who have read the book was a unanimous number because the book was a runaway bestseller and tickets to see its author were somewhat pricy, compared to most author events, which are usually free in bookstores or $5 at Town Hall – but worth it!. (I went as a patron ticket-buyer and not as a comped member of the press.)

When Flynn and Semple jokingly suggested that people who hadn’t read the book get up and leave the room for five minutes, one person actually obliged.

Gone Girl is a fast-paced, psychological thriller that alternates between Nick’s and Amy’s points of view, and its ending is polarizing to a lot of people because it doesn’t wrap itself up nicely in a way that satisfies everyone. Flynn said that people will wait twenty minutes, or more, to talk to her after a reading to just plop their book down in front of her and say, “I hated the ending.” She said she writes, “I’m sorry you hate the ending” in their books. (She signed, “To Chris, Who liked the ending! Thanks!” in my hardcover copy.)

But life very rarely wraps up nicely, and neither does great art, so I always found it revealing when people would talk about how openly hostile they were to the ending, and not in a flattering way. I told her I thought as much when I had the chance to talk with her. But the ending is consistent with the book, and another one, where it wraps up nicely and justice is served, would have taken the book in a direction that was unnatural to its tone and pace. Apparently even Bob Woodward agrees with me:

Bob Woodward on Gillian Flynn's Gone Girl: "That's the only way the book could've ended!" #SALFlynn

— SAL (@SeaArtsLectures) April 18, 2014

I also love the ending of the book because I suspect it might give Nancy Grace an aneurysm, were she to read it.

The first thing Semple said to Flynn was that despite Flynn being successful, famous, beautiful (and a few other superlatives I didn’t capture), she was glad to see Flynn was fat (she was visibly pregnant).

When it came to talk about adapting Gone Girl as a film, Flynn said the first draft of her script was 380 pages, and 150 is considered “too long” by Hollywood standards. “Can we make it a mini-series?” she joked. But the film is directed by David Fincher, who had (spoiler, sorry!) Kevin Spacey deliver Brad Pitt a box with Gwyneth Paltrow’s head in Se7en and refused to make Mark Zuckerberg patch things up with the Winkelvoss brothers in The Social Network, so it was perplexing to me that Flynn was reportedly changing the ending in the film to be more satisfying for filmgoers. Though she said that there is often a problem with films being too faithful to their source novel, she denied that she was doing that with Gone Girl. “There’s this internet rumor that I wildly changed things,” she said, “that it’s now a musical.” For her part, Flynn singled out The Talented Mr. Ripley and Fight Club (a David Fincher film) as successful film adaptations that didn’t feel beholden to their books.

There are reports and quotes elsewhere from Flynn that says there are significant changes in the ending, it just doesn’t appear that they are there to appease some focus group or people who expect their films to always wrap up perfectly. I find that very exciting. Way more excited than I would normally feel about a movie that stars Ben Affleck (Rosamund Pike plays Amazing Amy).

At one point in the talk, Maria Semple asked Flynn to read the “Cool Girl” part of Gone Girl. That is (she reads further than I quote, but you can read the whole quote here, or better yet, read the book):

Men always say that as the defining compliment, don’t they? She’s a cool girl. Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she’s hosting the world’s biggest culinary gang bang while somehow maintaining a size 2, because Cool Girls are above all hot. Hot and understanding. Cool Girls never get angry; they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want. Go ahead, shit on me, I don’t mind, I’m the Cool Girl.

Semple asked Flynn if she included a way to include the “Cool Girl” part in the film because it was an internal monologue and not spoken dialogue. Flynn said of course she did. It’s something we could all agree on, and be optimistic for.