I’ve seen Robyn Hitchcock play at least five times since I first became a fan some 27 (yipes!) years ago, but for the last decade I’ve been guilty of having taken the very prolific, one-of-a-kind English singer/songwriter for granted. After seeing him play Columbia City Theater last August, that’s a mistake I’ve vowed not to make again. He returns to Columbia City Theater for a live set this coming Monday, March 16 (tickets, $22 in advance, are still available). Do yourself an enormous favor, and catch him if you can.

To these ears, Hitchcock stands as one of rock’s great troubadours. He essentially does with lyrics what Salvador Dali did with paint, capturing the absurdities, horrors, and wonders of life, love, and the universe with surreal brushstrokes that—outright weird as they sometimes get—always maintain an affecting core of universal truth. A lot of musicians play-act at boundless creativity and eccentricity: for Hitchcock, it’s as unaffected and natural as breathing.

His career as a rock musician began in the late 1970s as lead singer, guitarist, and principal songwriter for The Soft Boys. Hitchcock firmly established his MO with the band—classic English rock songcraft wedded with sometimes strange, sometimes hilarious, always devastatingly effective lyrics. Hitchcock struck out on his own beginning with 1981’s Black Snake Diamond Role, and he hasn’t stopped since.

After establishing a dedicated cult with his solo work, he and his second backing band The Egyptians landed a major-label deal with A&M Records. The first release during that flush of success, 1988’s Globe of Frogs, introduced a lot of people (myself included) to the man’s unique world view and gift for indelible melodies.

Globe of Frogs bowled me over when I first heard it all those years ago, and I listened to it obsessively for months. Hitchcock’s brilliance didn’t form in a vacuum, of course—he’s openly acknowledged Syd Barrett’s influence on his knack for vividly-bizarre lyrics, and his melodies largely draw from Beatles-style harmonics and Dylan-esque folk—but he lent his own distinctive signature to those familiar elements. Insidious melodies abounded (try not to bounce your head happily to the jaunty, endearingly goofy “Balloon Man”), but the rest of Globe of Frogs was musical painting of the richest variety.

The record’s title track, with its sparse exotic percussion, spectral piano, and Hitchcock’s elliptical but evocative words felt, literally, like stepping into some mysterious, secret world. And unconventional as his lyrics were, they often hit with bracing directness. In the eerie sea-shanty/dirge “Luminous Rose,” he croons a line that remains one of the most profound strings of words I’ve ever heard in a pop song: “God finds you naked and he leaves you dying/What happens in between is up to you.”

After experiencing that record, Hitchcock’s back catalog and successive releases persistently occupied my stereo for the better part of a decade. Most striking about all of those efforts was how he was able to easily switch back and forth between trippy psychedelia (“The Man with the Lightbulb Head”), sterling pop (“So You Think You’re in Love”), and fragile British melancholy (the achingly gorgeous “Autumn is Your Last Chance”), touching on an array of classic influences without being subsumed by them.

Hitchcock’s muse has remained incredibly consistent over the years. After migrating from A&M to Warner Brothers in the ‘90s, he set up camp with indie label Yep Roc Records in the early 2000’s, and catching up with the lower-profile but still great albums he’s released in the ensuing decade-plus has represented some of the most rewarding music-nerd catch-up I’ve ever experienced. His voice—a singular, reedy tenor that swings between angelic sweetness, the impish playfulness of a truant British schoolboy, and a sometimes eerie deadpan—hasn’t aged a day, and his latest long-player The Man Upstairs combines Hitchcock’s still-sharp original songs with some well-chosen covers (his spare acoustic version of the Psychedelic Furs’ “The Ghost in You” will make you swoon). The album, like so much of Hitchcock’s work, feels classic and timeless in equal measure.

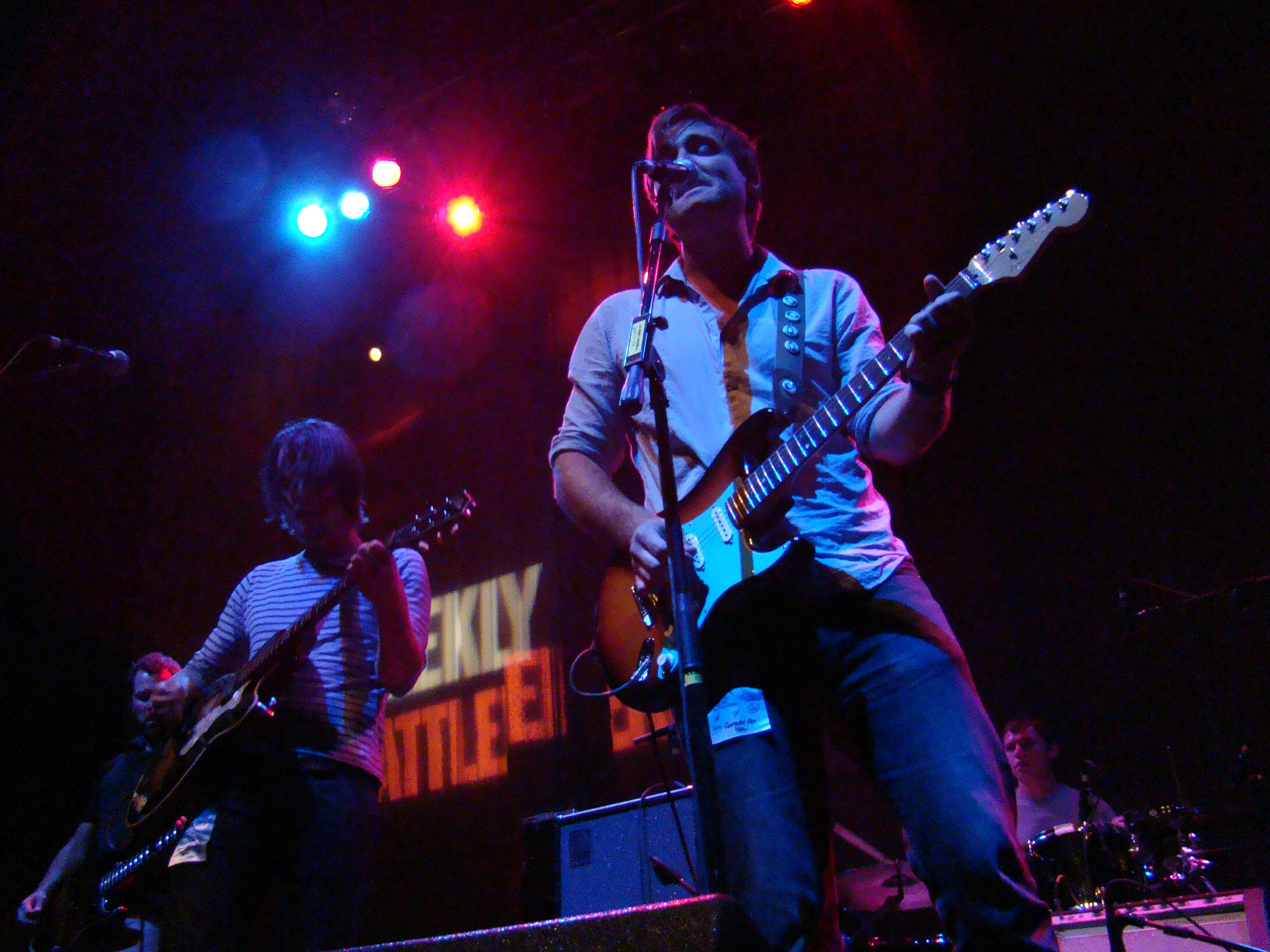

He also delivers one of the best live shows you’ll ever see. Hitchcock usually plays solo sets, and he’s capable of summoning up all the richness of his most psychedelic work with nothing more than his voice and an acoustic guitar. Best of all, his onstage banter alone merits the price of admission. Expect stream-of-consciousness tangents that include everything from minotaurs to giant irradiated astronauts, and blasts of hilariously pointed socio-political commentary. Once you see him onstage you’ll be hooked, and here’s hoping that unlike me, you’ll never take Robyn Hitchcock for granted.