This program plays at Benaroya Hall tonight, September 29, at 7:30 p.m. and Saturday, October 1, at 8 p.m. Tickets here.

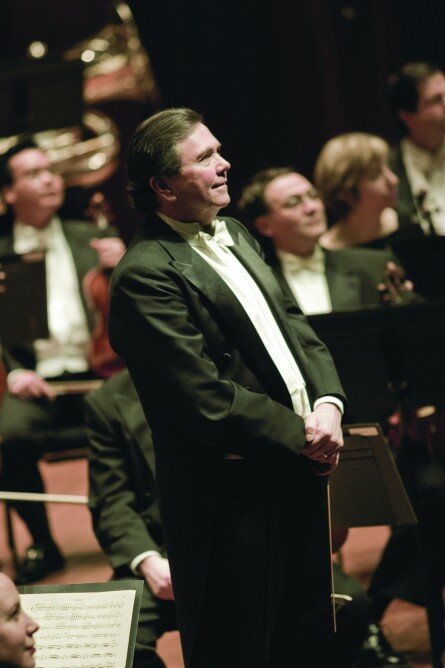

It’s a delight to see fresh winds blowing at Seattle Symphony, courtesy of its new young music director, Ludovic Morlot.

For this week’s concerts, he announced he was celebrating rhythm, but as well as pulsing with rhythm, the Benaroya Hall stage exploded with musical excitement, flavors and colors on Thursday night, and the audience responded with enthusiasm.

Morlot programmed two very familiar works, Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, and Gershwin’s An American in Paris, but then he added a composer who is not nearly as familiar, Edgard Varèse, and his work Amériques. This last choice is in accord with another statement of Morlot’s that he wants to introduce less familiar works to the audience, expanding our horizons.

Many of us are dubious about having our musical horizons widened. “We never heard of this composer. What if we don’t like it? I don’t want to pay money to go to hear somethiing I won’t enjoy.”

Never fear. So far Morlot may be bringing on music less familiar to us, but he is doing it with a discriminating hand, and a good understanding of what the audience will embrace. I heard from one concertgoer last week who had been to the concert including music by Dutilleux and Frank Zappa. She had enjoyed it so much she went out and bought a ticket to hear it again the next day.

Thursday night, Morlot created the same enjoyment. The three works were all written within a span of about 15 years, Rite in 1913, Paris in 1928 and Amériques between 1918 and 1922. It was a time of artistic ferment in Paris, even during WWI, beginning the same kind of musical upheaval which had occurred in Italy at the very end of the 16th and early 17th centuries when the Florentine Camerata and composers like Monteverdi realized that one could express all kinds of emotions dramatically in music, culminating in the birth of opera.

This time the innovation which redirected musical directions for the future was spearheaded by the Rite, the premiere of which produced near pandemonium in the theater. It’s not so far out for us today, but its onslaught of vitality, excitement and tension, its shrill discordance, unusual—to them—harmonies and sawtoothed rhythms, the seemingly disorderly cacophony, was a shocker.

All of these were present in Morlot’s performance Thursday. He brought out the musical colors and the unexpected instrumental combinations, used the sudden quieter moods and the silent pauses as clear contrasts to the relentless clangor, and he shaped the whole so that it hung together as a work. It is easy in this work to have the orchestra playing at full volume almost throughout. He never did. There was plenty of volume, but it never reached a fullscale assault on the eardrums.

Gershwin’s An American in Paris is much less wild, more urbane, and great fun. Morlot chose to perform it two weeks ago at the SSO’s opening gala, and I reviewed it then in this space. Suffice it to say I enjoyed it as much Thursday. In Morlot’s hands, this is a piece with a grin on its face, exuberance in its heart, and wings on its feet.

Varèse was born only a year after Stravinsky, in 1883, and many of the same world influences worked on him. Well before he wrote Amériques he began to look for different sounds, different instruments he could use, and was not thinking along the lines of the romantic composers he grew up hearing. Amériques which he wrote after he arrived in New York is like Gershwin’s Paris in that the sounds and ambience of the city captured him, but it is much harder to distinguish them in the music. If you listen very carefully you can maybe hear the clopping of horses’ hooves, the foghorn, or the cries of vendors, but the only unmistakable city sound is the siren which he brings in often.

Morlot said from the stage that he deliberately put this on the same program as the Rite, as the influence of the 1913 work on the 1918-22 one is obvious. Varèse uses winds similarly, and, importantly, the music has the same flavor, often even similar harmonies, and has a similar impact on the hearer. But his ideas on melody—he called it “organizational sound”—and his huge use of percussion, eleven of them and two timpanists, are all his own, as is his imagination.

However, it does feel closely akin to the Rite in every way, and that leaves one wondering why the Rite caught on and is heard everywhere, and Amériques much less so. It was fascinating to hear the two in juxtaposition. Both are noisy works, and no one could call the Gershwin a quiet dreamy piece, but the effect of all this loud exuberance did not leave this audience member with ears ringing from the blast. Rather, Morlot kept the volume at just under that point, until the last measure of the Varèse when, having thought before the orchestra was playing at full, it suddenly became an amzing blast of sound.

As Gershwin would have said: Fascinating rhythm.