Seattle Shakespeare Company is making a strong argument for your choice of Love’s Labour’s Lost (through April 6) as your favorite of Shakespeare’s comedies. This is astonishing as the play has a reputation for being as unwieldy as its title and riddled with obscure intellectual banter and philosophy. It includes scenes full of Latin, wordplay comprehensible only by footnote, and the utterance of the word honorificabilitudinitatibus (I dare you even to try say it).

There isn’t a weak link in the production — in fact, two immense strengths raise it from Seattle Shakespeare Company’s reliable competence to something approaching greatness. These strengths are found in newcomers: Paul Stuart, in the leading role of Berowne, delivers the text with ringing clarity and nonchalant charisma in his Northwest debut. Also new and notable is first-time Seattle Shakespeare Company director Jon Kretzu.

Kretzu’s production begins before the audience enters with a rowdy party populated by infantile young men one might take for frat boys in white tie and tails. There is also a battle-scarred Il Capitano, a black cravated boy, and a malevolent-looking derelict clown. Everyone is in action with one exception who appears to be a kind of servant (a riveting Brandon J. Simmons). He is a monument of stillness and a foreboding counterweight who leaves a lasting impression with hardly a word.

There isn’t much plot to Love’s Labour’s Lost. The King of Navarre (Jason Sanford) and the young men of his court swear oaths to three years of ascetic study without romance. They break those oaths when visited by the princess of France (Samara Lerman) and her attending ladies. Meanwhile there’s some vulgar clowning and academic wordplay by the commoners and Don Armado (David Quicksall).

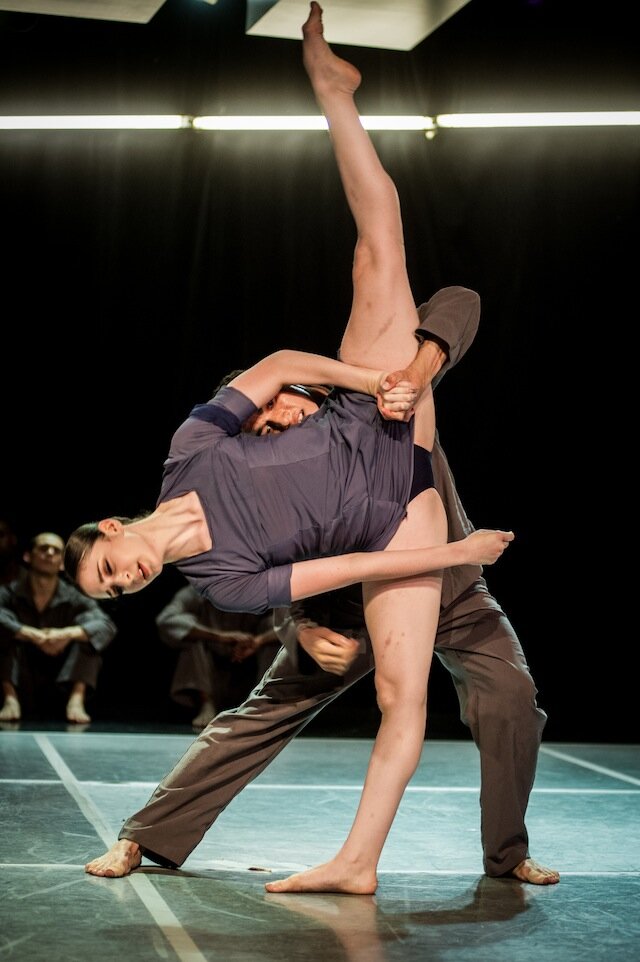

While the first half of this performance establishes and then breaks the academic oaths the second half is all revels. The conflict is mostly flirtatious teasing and merriment. If there is an antagonist, it is the persistence of youthful indiscretion. In all the frivolity, frat-boy antics drive the young men, taking them nearly over the top before they give action to their yearnings. The anarchic devolution of their revels into baiting and abuse is cut short by the shocking denouement—which is only an emotional shock and overtly predictable as plot. These young men refuse to mature until forced to it.

While Stuart stands out boldly the rest of the cast does fine work as well including Donna Wood who appears to be reprising her role from last year’s Seattle Shakes production of As You Like It. Though that show’s Audrey had far more to say than does this show’s Jaquenetta, Wood owns the type in both instances.

David Quicksall makes Don Adriano de Armado surprisingly likable, playing up his vulnerability to deflate a potentially grating arrogance. The Spaniard winds up falling into the vein of Sir Toby Belch and Falstaff.

Mike Dooly goes more flat-out commedia with his Costard. Dooly takes this play’s most overt clown to the dangerous territory of Harpo Marx with a leer replacing Harpo’s relatively innocent smile. For him life is sex, wine, food, sleep, and casual violence, and yet he is irresistible.

The technical work is excellent across the board with lights, set, and sound all heightened without distracting, and costumes that hew to both character and the 1920s setting. Kretzu pushes the limits a bit with physical and prop bits that start to feel gimmicky but the gimmicks are a phase on the way to stratosphere of either silliness or mayhem. Marleigh Driscoll’s props are key in these achievements with a collection of period oddities that tug the staging into focus.

Kretzu counters the antics with a sudden gut-punching turn to darkness that leaves the whole theatre suspended. That balance fits this comedy, as it ends with only the promise of still-distant nuptials. Thankfully audience satisfaction and lightened hearts are immediate and guaranteed.