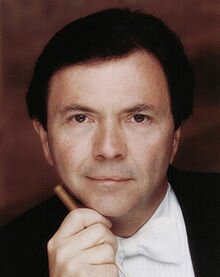

The Seattle Symphony’s laureate conductor, Gerard Schwarz, returns to the podium for this week’s concert pair at Benaroya Hall (April 28; tickets), including the world premiere of a suite from Daron Aric Hagen’s opera Amelia (Schwarz conducted the world premiere at Seattle Opera two years ago). Together with Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with Alexander Toradze at the keyboard and Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 8, it makes for an unusually long concert, a two-and-a-half-hour performance.

Hagen’s Five Sky Interludes, thirty minutes of orchestral sections bridging or introducing scenes in Amelia, are full of themes which pervade the opera, but for those who don’t know the psychological baggage of that story, they didn’t convey much. The work is based on a bland lullaby, introduced in the first interlude. While there are flashes of interest in the second, it’s not until the third that anything exciting happens. This one, depicting the state of mind of Amelia, gets ever more feverish and cacophonous. While well organized and orchestrated, the whole work seems a bit earnest, uninspired, though there are nice touches like the use of bells and a trumpet toward the end.

Unfortunate to pair this, then, with the brilliance of Prokofiev and the emotion in Shostakovich.

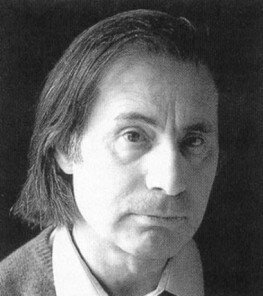

The former’s third concerto requires extraordinary technique from the soloist, which Toradze has no trouble in providing. Much of it the work is played at lightning speed. Toradze, like an elderly elf with his frill of white hair around a shining pate, used his whole body in the act of performance. His hands, a blur on the keyboard, were accompanied by his body rising right off his seat, while his feet, both of them, kept the rhythm with stamps and taps, even when the toe was providing the necessary pedalwork.

A notable Prokofiev interpreter, his playing could as easily be a soft expressive caress on the keys as a formidable cascade of coruscating notes. Schwarz and the orchestra stayed closely with him throughout, always allowing the piano’s role to come through.

Schwarz has done well by Shostakovich in the past, but in recent years he has tended to veer towards demanding louder and louder sound from the orchestra more and more of the time. The performance of the Eighth suffered from far too much fortissimo, to four ‘f’s, negating much of the nuance which can be present. At the same time, he also at times elicited some beautiful soft playing from the musicians.

Shostakovich gives long solos to several instruments, including several we don’t often hear from at such length and in such prominence, such as Zartouhi Dombourian-Eby’s piccolo and Larey McDaniel’s bass clarinet. It’s always a pleasure to know we have such gifted and expressive players in the body of the orchestra. However, Schwarz had the piccolo at such volume that it was sometimes painful to the ears, even in Row Q, and particularly when combined with the cymbals.

Both these works brought enthusiastic applause from the audience, which had also given Schwarz long applause when he arrived on stage at the concert start. He will be back on the Benaroya podium May 15-17 for performances of Bartok’s dark opera Bluebeard’s Castle, with the unusual sets by Dale Chihuly.