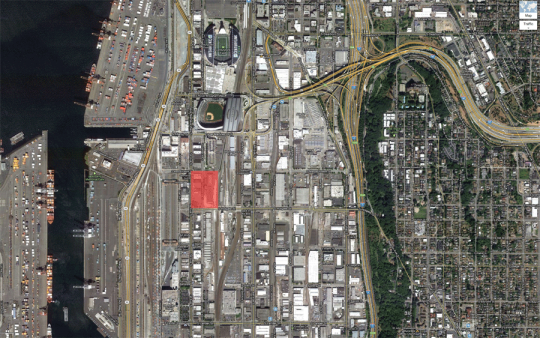

On September 24, 2012, the Seattle City Council voted 6-2 to authorize Mayor McGinn to “execute a Memorandum of Understanding” with King County and ArenaCo, the last being the entity that, led by Chris Hansen, hopes to build a basketball arena in SoDo.

The Council’s Tom Rasmussen managed to miss out on this hotly debated vote. Richard Conlin and Nick Licata supplied the No votes. Both have now written explanations of their reasoning, with Licata seemingly of two minds about the deal. Concluding his analysis, Licata sounds more like a Yes: “In summary, I believe this proposal is a good one; it meets a high bar for public accountability. It is a rather solid tree in a forest of not such sturdy timber.”

But judging the proposal not simply on its merits, but on the other priorities of the city, Licata ultimately decides a new basketball arena is not Job #1. (He does not, however, suggest any alternative use of municipal bonding authority that the arena’s construction would forestall.) But fair enough.

This formulation, in contrast, is something of a drive-by: “They see someone purchase private land and in a couple of years get the city to buy it from him for double the price he purchased it for.” Since the purchase price has yet to be negotiated, it is premature to use the cap on the purchase price as the purchase price itself.

Conlin’s argument is pricklier from the outset. He says that though the revised agreement may do more to shield the city from downsides, it’s by no means clear that “we will wind up benefiting from it, or that it is a good use of the City’s time, resources, or financial capacity.” (In both Licata and Conlin’s arguments there is a tendency to elide the fact that basketball fans are also citizens.)

Conlin, who studied history as an undergraduate, sounds like a history major still when he argues that, “Only since World War II has it become customary for local governments to be primary funders–and the current trend may be away from public finance.” For one, that “only” refers to about 70 years. And his trend furnishes one example: the Golden State Warriors.

Licata and Conlin are, essentially, dismayed by a public-private partnership that they see as making off, somehow, with city monies. They sound particularly aggrieved by the new arena’s “self-funding” mechanism, where taxes paid by arena-goers would be directed to paying its debt. As politicians, both demonstrate the ability to annex notional revenues, and to cry out in pain at the thought of their hypothetical loss.

Speaking of notional revenues, both refer to “income” from Key Arena, which they half-rightly see as a white elephant. (“Half-” because it is a 50-year-old white elephant regardless of what happens with a new arena, though the two insist there’s a causal link. The more hard-headed wonks at Seattle Transit Blog are ready to knock it down, which is probably the best thing.)

Conlin claims the Key “made $310,000 on $6.6 million in revenues” in 2011. This is very similar to the “profit” the city looted from the Monorail for years, while foregoing essential maintenance and improvements; Key Arena’s infrastructure is in no better shape. Properly speaking, the Key’s depreciation wipes out any consideration of profit from operating expenses. Licata meanwhile mourns the $100 million in taxpayer money already spent: He could take comfort in realizing that works out to, over the Key’s lifetime, just $2 million per year.