Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry, now ensconced in an old armory on the shores of Lake Union, is still settling in in other ways. General admission is now $14 (free for kids 14 and under with an adult), and the site gamely tries to prepare visitors for a South Lake Union hunt for parking, with a link to what’s happening with Mercer Street construction. It’s open daily 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. (Thursdays until 8 p.m.).

Inside, the first thing that strikes a long-time patron is the sense that the museum finally feels less like Fibber McGee’s closet, with odds-and-ends piled deep, over here a neon sign, in another corner, a plane. Formerly, the ratio of nostalgia to historical import could tilt toward the former, at least in terms of what was on display — MOHAI has long been in danger of being the attic where Seattle keeps the signs for iconic, defunct businesses: Lincoln Towing’s big, pink toe (tow) truck, the Rainier “R,” the P-I globe.

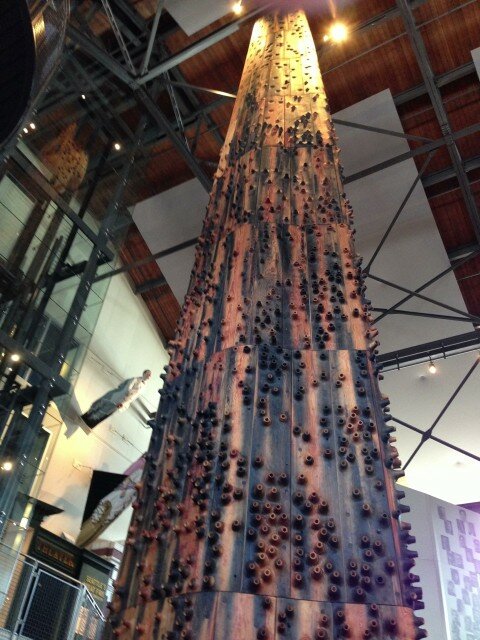

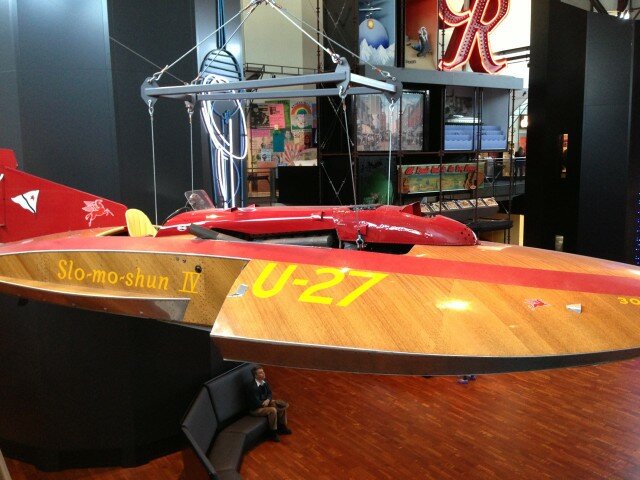

At the armory, MOHAI is laid out vertically, and visitors wind their way around the edges of central open space that dwarfs a Boeing B-1 (its floats designed by George Pocock) and a legendary hydroplane. The new venue’s layout gives the museum, which claims to possess some four million artifacts, room to breathe, so that when you stumble across the wooden sandwich board advertising the original Starbucks, it stands out. Interpretative trails wind through exhibits that catch Seattle rowdily welcoming the WTO, sluicing away its steep hillsides, packing Japanese-Americans off to camps, or ripping up its streetcar network.

Multimedia presentations let you learn and practice speaking Chinook jargon (you may already know that “hee hee” has something to do with “laughter”), or be grilled by threatening voices on the look-out for Un-Americans. Up top, everyone waits their turn at the periscope. A temporary exhibit on Seattle’s film history is easily good enough to be a permanent display. (Sports? It’s technically true that Montero is history, but that section lacks focus.)

One weakness is that too much of the illustrative text is written with school field trips in mind, supplying facts of interest, without grappling too deeply with context. That said, it’s just plain nuts that a “playful sound and light show evokes the cataclysmic Seattle fire of 1889,” as reports the New York Times. The Great Fire destroyed 29 square city blocks, and though no one was killed, it hardly sounds playful. Besides, as it’s generally agreed that the rebuild marked Seattle’s transition from frontier town to city, it seems a wasted opportunity.

But the Times is right to marvel about “the extent to which nearly everything about Seattle is engineered” — the geography certainly, from reclaimed tidal flats to those hosed-down hills, but also the roadways made of wooden planks, the streetcars that passed over ravines on trestles. An engineered landscape invited engineers: Boeing, and all its subsidiary contractors. The hardware engineering spawned the software engineering of Microsoft. You could also say that Amazon engineered online retail, or that Starbucks engineered espresso drinks at scale. (A complementary narrative is that of the Seattle outfitter: from the Yukon-bound, to Nordstrom business casual, to REI and its outdoors brethren. Seattle likes kitting itself out.)

It takes time for a museum to learn its space, to see itself as an artifact that people engage with. We can hope that, in time, MOHAI’s interpretation of its holdings will grow more innovative — less placard-on-the-wall and more engagement with the artifacts themselves.