Ironically, it is fairly easy to get a fix on Third Avenue in Seattle (or get stabbed or beaten nearly to death) because it has become the entrenched home of a large open-air drug market. But the City of Seattle has so far struggled to fix that problem. Better crowd control late-night, when bars are letting out, has helped reduce aggressive brawling, and despite bullets flying less frequently, overall confidence in personal safety is still low.

It’s not that the City is unaware. The City Council’s Tim Burgess writes on his blog: “Residents and small business owners in Belltown send a steady stream of complaints to Council members and the Mayor asking why drug dealers are allowed to sell heroin and cocaine with near impunity near their homes and shops.” Let’s start, he suggests, “with an increased presence of uniformed police officers.”

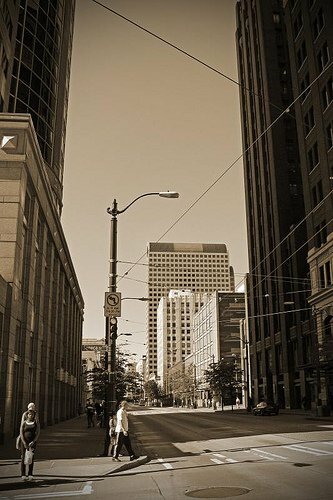

Burgess also thinks Third Avenue could use a facelift in general:

It should be converted into a restricted “complete street” that serves only transit, pedestrians, bicycles, and delivery and emergency vehicles all day. Sidewalks could be expanded and streetscape improvements installed, such as hanging flower baskets and other “green” enhancements, public art, wayfinder signage, and additional lighting.

Is it possible to stop Belltown’s illegal drug market?, asks Seattlepi.com. A 2009 sweep of drug dealers, reports Casey McNerthney, led to 32 being charged. But they soon popped up again. SeattleCrime.com’s Jonah Spangenthal-Lee calls them “catch-and-release drug arrests.” Newly ensconced at Publicola, Spangenthal-Lee details the city’s new drug diversion program, which seeks to separate the major dealer wheat from the small-time chaff.

Beginning October 1st, small-time drug dealers and drug users arrested with less than three grams of crack, heroin, meth or drug paraphernalia in Belltown by members of SPD’s West Precinct Anti-Crime Team and bike patrol officers will be given the option to go to diversion DEFINE or go to jail as part of the Law Enforcement Assistance Diversion (LEAD) pilot program.

Essentially, the program tries to distinguish between addicts selling (or carrying) to support their own habit, and the more troublesomely entrepreneurial dealer. Addicts will get “housing, social security benefits, job training, or on-the-spot treatment,” and aren’t booted from the program for relapsing, as addicts will do. If there’s an 80/20 rule in effect, this should have the effect of emptying the sidewalks and pocket parks of small-time illegal activity, providing less cover for the serious drug dealers.

“LEAD, which costs about $1 million a year,” says Spangenthal-Lee, “already has enough funding to run for the next four years.”