Royal Blood, the latest play from local playwright Sonya Schneider, made its world premiere last weekend at West of Lenin. While not quite perfect, it’s a family drama that I have been unable to stop thinking about once I left the theater Sunday evening. It’s engrossing. It’s about the lies we tell our families, and ourselves, in order to get by.

In the small, Fremont theater, intimacy is conveyed between the audience and performers by an assortment of lawn chairs, benches. The set, designed by Stranger Genius Jennifer Zeyl, faithfully recreates the backyard of a California house, falling apart as much as the family who inhabits it (or maybe I’m projecting).

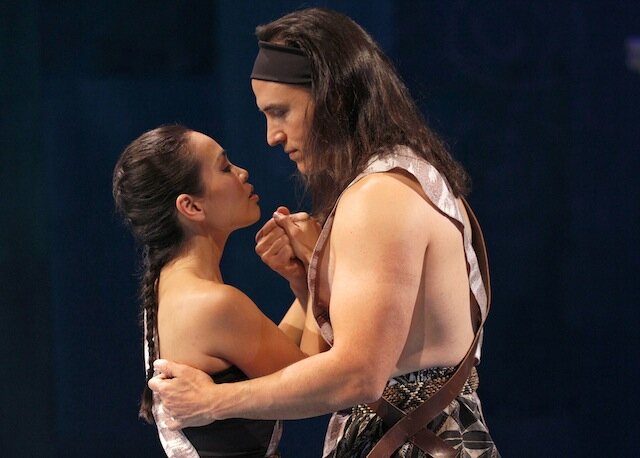

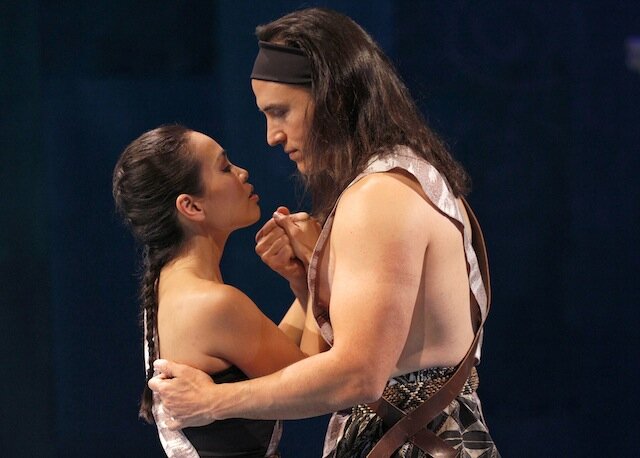

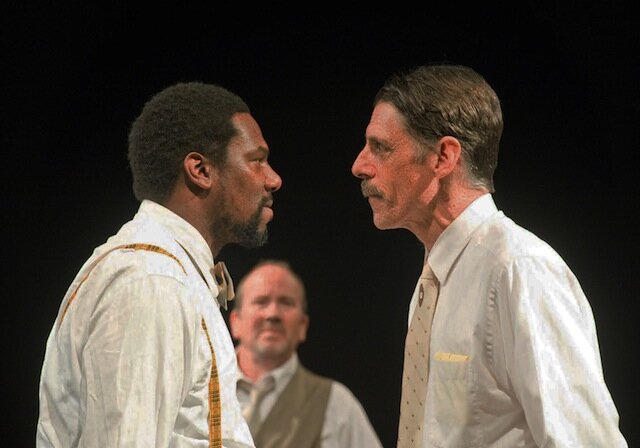

Todd Jefferson Moore plays Cliff, the patriarch who is slowly dying of cancer, raising his mentally disabled daughter Deborah (a wonderful performance from Amy Love), and having to come to terms with the suicide of his son. That his son’s lover, Adam, is Japanese and Cliff hasn’t quite gotten over World War II (where he served) complicates things, so he uses his racism as a defense to shield his homophobia. Yet through Schneider’s writing and Moore’s performance, you can feel a lot of empathy for him as he tries to hold his family together, knowing he doesn’t have much time left. It’s probably the strongest performance of the play because you can sense that he’s only a few bad cards away from a complete breakdown, or explosion, as it may be.

Mari Nelson plays Dorothy, the oldest daughter who is a Europe-based journalist. She was once nominated for a Pulitzer Price, and now she sees every step and every story as a means of advancing her career, which has priority over her family. She’s supposed to be the adult of the family. Cliff even tries to outsource telling Deb about her brother’s suicide to her. He told Deb that her brother is just away on a cruise, which he won for being the 101st caller. Dorothy is the only one in the family realistic (or cynical) enough to believe her mother’s claim that she’s a distant blood relative of Princess Diana. Her character slowly unravels, though, as you watch how she interacts with her sister, her father, and her daughter, Cassiopeia (who shows up unannounced after she runs away from her father’s home to her grandfather’s; she’s played by Nicole Merat). She’s not a bad person, per se, but a complex one who is trying to balance the family she never asked for with the life she desperately wants for herself. She doesn’t want or need anyone else in it, but her family very much needs her.

Deb, for her part, thinks that Dorothy is visiting to help her bury her dog, Lady Di, not her brother. She’s painfully naïve but it’s her lack of any cynicism that makes her the most sympathetic character in this play. Everyone wants to protect her from being hurt, even if they have different ideas of how that should be done.

The family communicates with each other through secrets, lies, half-truths, outright evasions, and the occasional dose of hard truths. It’s not gentle or subtle, but it’s how they can get the truth to one another.

The ending, no spoilers, felt like a let down and like it was the only way out of the box Sonya Schneider built for her characters. Yet the challenge of the piece is to not just understand the motivations of each person on stage (and off, like the dead brother and mother) but to show genuine empathy.

(Royal Blood plays at West of Lenin on Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays, through Friday, April 4. Tickets can be acquired here.)