Brian Stelter normally reports on media for The New York Times, but he’s also a self-confessed “weather geek,” which is why when I sit down with him for an interview about Page One, the documentary he appears in, he’s just back from tornado-ravaged Joplin, Missouri–and still processing.

“I want to buy new shoes and a raincoat,” he says. “I was wearing these shoes. I feel like I was walking through a cemetery.”

As it happened, he owes the experience to Oprah. He’d “raised his hand” to cover a few storms over the past year, but the timing had never worked. This time, he was flying to Chicago for Oprah’s last show and when he landed in Chicago the departure board showed a flight in an hour to Kansas City. He called the national desk and told them, “I could be in Joplin by noon,” and they said to catch the plane.

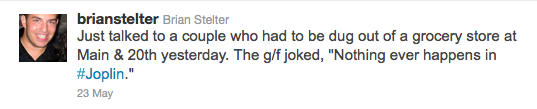

Reporting what he saw was difficult because “communication was really, really weak. It was almost impossible to get a phone call or an email out.” He ended up turning to Twitter: ” I thought Twitter was my best reporting, my most immediate reactions.”

His story in the Times retains the telegraphic qualities of on-the-ground impressions:

His story in the Times retains the telegraphic qualities of on-the-ground impressions:

Lauren Johnson used her iPhone as a flashlight to trek through the basement where she had taken shelter with her father when the storm enveloped their neighborhood.

She shook her head as she walked upstairs. “Our neighborhood, it” — she paused — “it ceases to exist.”

As one of the “next generation” of journalists at The New York Times, Stelter treats multi-platform reporting as a fait accompli, telling me that he gets “annoyed with some of my colleagues in the media who only use Twitter as a one-way medium. I also like using it to talk back. To anyone who replies to me, I try to reply back. I have this crazy idea that if we reply to people maybe they will be one percent more likely to pay,” he says, referring to the Times‘ newly instituted, much discussed paywall.

“People are going to know you’re the one to go to when they have a story idea,” he continues. “When they have a tip. When they’re pissed off about something.”

As for the paywall itself, “it’s early days,” he says. “We haven’t had firm numbers on the paywall yet, we’ve been told it’s exceeding expectations. I think the journalists in us would like to know what the expectations were. We’d like to see the raw numbers, but I understand that they share that with investors before they share it with us.”

As someone who’s been “nervous about the paywall, nervous about losing audience, nervous that people my age wouldn’t pay,” he admits, he’s heartened by the news that people are in fact paying, and that he has not heard his readers complaining about not being able to read articles. “That’s how it affects writers,” he adds, “writers want to reach the broadest number of people they can.”

Stelter plays the incredible shrinking man in Andrew Rossi’s Page One documentary (playing at SIFF twice more: May 28, 11 a.m. at the Egyptian and May 30, 3:30 p.m. in Everett, where Stelter will appear for Q&As). He happened to go on a diet as the film began, and lost 90 pounds during filming. He and David Carr get significant screen time, for different reasons. Carr comes across as the hard-nosed (but adaptable, and warm-hearted) veteran, generating huge stories like the Chicago Tribune management frat-partying the paper into bankruptcy, while Stelter, recruited from his blog TVNewser, is always-on, tech-savvy, and thoughtful about his coverage of what could be a parade of media glitz.

“There’s still too much chasing of the ball, blindly,” he argues. “Especially when it comes to court cases and celebrities and entertainment news. I think a lot of that is on the television side.”

Stelter is quick to point out that television news can of course do fine work, but there’s a damning scene in Page One about a story of Stelter’s that didn’t run, where NBC seems to announce the end of the Iraq War to their viewers, massaging a convoy of trucks into a “Mission Accomplished” moment. The film shows New York Times staff frantically checking to see if they had somehow missed the memo from the Pentagon, and ultimately deciding that they would simply ignore this bit of theater.

“To watch my editors decide not to run my story was interesting because–frankly I can’t disagree with them, they made the right call–but I never get to see that back and forth between editors,” says Stelter. “Same with the page one meeting [in which editors pitch stories for coveted front page placement]–to see something that I can’t actually go to, that was pretty exciting.”

In contrast to his blogging days, Stelter says he finds the newsroom a “more deliberative” environment.

The final product is more of a team effort, a team production. There are days when that annoys me because I just want to get the story up, but the final product is almost always better when my editor and I have talked it out, hashed it out, and fought over it a little bit…. What comes out ends up being a lot better. So much of journalism is really storytelling–we’ve grown up as storytellers verbally and visually, we don’t generally tell stories in print, we tell them face to face, in person. I’ve been lucky I’m surrounded by editors who have the time to do that.

As much as Page One is an almost unfettered glimpse into the workings of the nation’s paper of record, it’s also a story of how the Titanic of the newspaper industry only sideswiped the iceberg.

As murky as the crystal ball remains, the film recalls the panicky moment when nothing seemed certain, when the Times engineered the sale-leaseback of its own building to generate capital. That and the mass layoffs, says Stelter now, feel “like the reactions of a trauma surgeon. For a while, I don’t think I knew how dire the straits were in ’08 and ’09, at times. It feels markedly better now.” It’s at this moment that The Atlantic chose to speculate on the unthinkable: the death of The New York Times, a story that still inspires some heated rejoinder.

But, Stelter points out, it’s not just the economy, stupid: Things were happening that were not as clearly evolutionary at the time: “the generation-long shift of audience from print to the web […] was happening in the middle of all these dire economic problems, and I think the film is able to hit on both. It’s able to show how our consumption patterns are changing, while at the same time, day to day, advertising revenue was collapsing.”

An associated campaign, Consider the Source, hopes to build on one area the film explores: the role of aggregators and search in relation to a news source. (“I like the Huffington Post, I read it a lot. I like how they repackage my stories,” says Stelter, when I ask if he’s bugged at all by Huffington’s recent payday.)

But there’s much more to the film: the reinvention of subscriptions as gadget-based (and the concomitant question of dependencies on third-party platforms like the iPad), the effects of Judith Millers and Jayson Blairs, the sea changes in overall business model.

The sheer amount of money that is needed to sustain fact-gathering (and fact-checking) remains a conundrum. “You think journalists are everywhere,” warns Stelter, “but there’s actually a rather small number of people getting the basic facts for us,” listing the few organizations that keep staffed overseas bureaus.

While he admits to chafing a little at speed constraints (“They created infrastructure so we can publish blog posts 24 hours a day, which we didn’t used to have. So we’ve made progress on that front.”), in the end, he says, “I don’t want to risk the Times‘ reputation even a little bit by putting [rumors] online. We take risks of other kinds, by putting people into war zones, we don’t need to be taking risks with our facts.”

You can hear the institutional voice of the Times in that–though Keith Olbermann might disagree on particulars. I was struck particularly by Stelter’s contention that, “Maybe it’s because I have better sources, but I don’t find myself [often] wanting to publish something and struggling to prove it.” In the film, the acid-test of that assertion comes as Carr brings sources speaking on background to talking on the record to the Times–a Chicago Tribune competitor. It’s far from easy, but as the Tribune would be eager to sue for any misstep, Carr knows he needs an ironclad story, and works like a terrier until he gets it.

“My readers at the Times don’t care as much about…rumors as my readers on my old blog,” concludes Stelter, who is supposed to be calling his agent back about ideas for a first book. “I want to write a television book, I just don’t know exactly what the topic should be. I think as a journalist you’re always looking for another challenge…. I’m so comfortable on 140-character tweets and 1,000-word stories–I know I can write those, I don’t know if I can write a book. I’m interested in that challenge.”