The three performances of Strictly Seattle at the Broadway Performance Hall last weekend were sold-out or close to it — always an impressive feat when it comes to contemporary dance, and even moreso if the student dancers range in skill from advanced to beginner.

It was part of Velocity‘s summer dance intensive, which brings dancers from all over the U.S. to Seattle. With Tonya Lockyer at the helm, Velocity has widened its already significant embrace of dance-makers in Seattle, maturing in its role as not simply a producer but an instigator of dance around Seattle, in public spaces as well at at the dance center on 12th Avenue.

Strictly Seattle offered students the chance to work with choreographers Ricki Mason, Mark Haim, KT Niehoff, Marlo Martin, Ellie Sandstrom, and Zoe|Juniper, and the results made for an eclectic evening.

Things started off with a champagne-cork bang, with Mason’s fizzy fantasia “There is no ‘I’ in Bride,” where everyone gets a chance at the veil and bouquet-toss in a music-video style opening. During the Flower Duet from Lakmé it becomes a Busby Berkeley scene, with dancers sliding their “catches,” posed, across the floor, or with the 20-plus-dancer ensemble flowing into pattern after pattern.

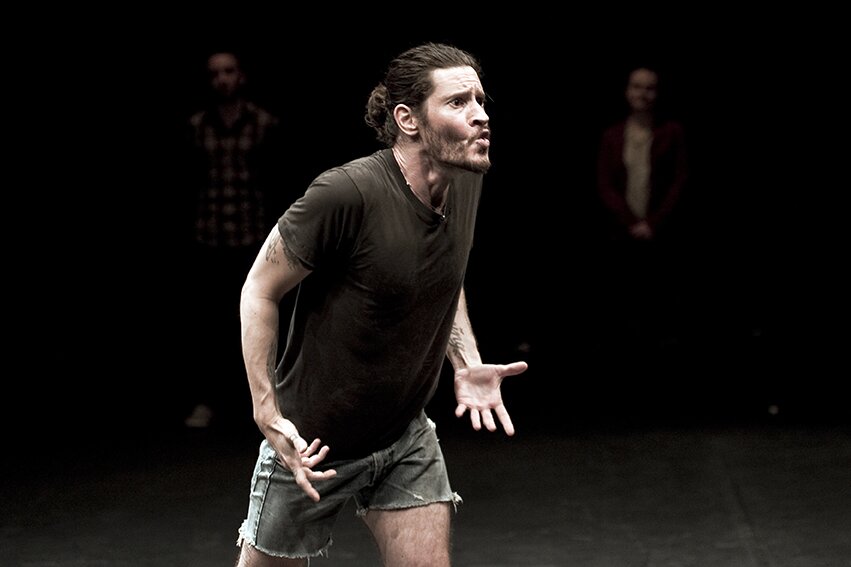

Mark Haim’s “…In Pieces,” which immediately followed, demanded an abrupt shift, built as it was on a score of excerpts from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf?, usually insults accompanied by the sound of something breaking. The dancers, costumed in Corrie Befort’s mid-20th-century Brit, appeared in trios and outcast solos. Haim’s choreography wasn’t violently representational (no hurled china) — it seemed nostalgic, even, for an era when people might have danced around their living room.

KT Niehoff’s “Tipping Point” happened almost entirely with the dancers sitting on the floor, their legs in a V in front of them. It’s a kind of programmatic dance, in four parts, with the fifteen dancers following a set of rules. Even if you don’t know that, it’s still an arresting piece because of its constraints — the dance takes place in the arms, torso, neck. As it built, first one dancer then another gained her feet to take up a bird-like posture, elbows out, head cocked and sweeping side to side.

Marlo Martin’s “Missing Pieces” opened with Kaitlyn Dye in a solo against a back wall — here the “against” refers to conflict, not a backdrop. Later came a kinetic duet — one partner almost climbed the other to soar then collapse on their shoulder, a hand encircled the back of a neck to herd the other along — that got picked up in a round that ran through the ensemble. The roar that went up for this fragmented, disjunctive piece rivaled that for Mason’s good-time opener.

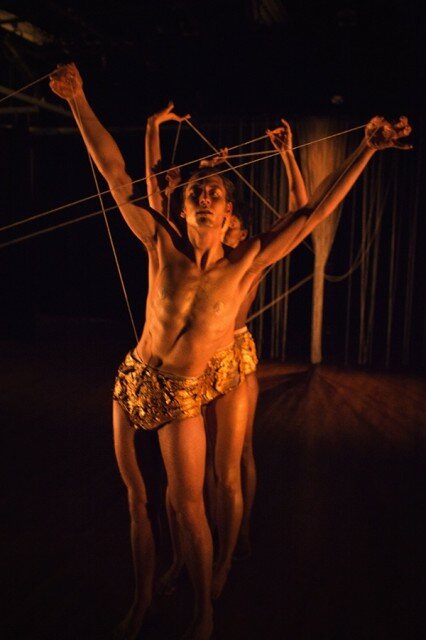

Ellie Sandstrom’s “Isolated Folds” didn’t make that much of an impression of newness on me; that isn’t a complaint, just an excuse for not having much to say about it. It, like Zoe|Juniper’s “eight,” seemed of a piece with what we’ve seen from the choreographers previously. “eight” had that ritualistic-rave air to it, the dancers in different colored briefs and tops, with stark shadows on the wall. There was the over-the-head slicing with arms, the attempt to close the book with a deep focus on the beat. It felt good, like a concert you were hoping would be good.