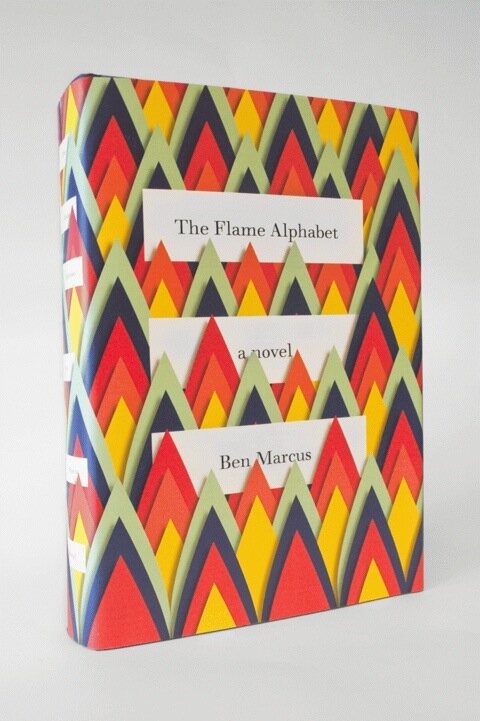

Ben Marcus reads from The Flame Alphabet tonight, January 26, at 7 p.m. at The Grotto at The Rendezvous (2322 2nd Avenue), in partnership with the University Bookstore.

That’s Jonathan Safran Foer, Jonathan Lethem, and Michael Chabon, who have all blurbed for Ben Marcus’s latest novel, The Flame Alphabet. Here’s Chabon’s outburst after reading the book:

That’s Jonathan Safran Foer, Jonathan Lethem, and Michael Chabon, who have all blurbed for Ben Marcus’s latest novel, The Flame Alphabet. Here’s Chabon’s outburst after reading the book:

Echoes of Ballard’s insanely sane narrators, echoes of Kafka’s terrible gift for metaphor, echoes of David Lynch, William Burroughs, Robert Walser, Bruno Schulz and Mary Shelley: a world of echoes and re-echoes—I mean our world—out of which the sanely insane genius of Ben Marcus somehow manages to wrest something new and unheard of. And yet as I read The Flame Alphabet, late into the night, feverishly turning the pages, I felt myself, increasingly, in the presence of the classic.

If you subscribe to any magazines that still publish fiction, you’ve likely run across a Ben Marcus story. He keeps popping up in Harper’s, for one. Here he’s taken a horror movie plot–literally, the one I’m thinking of is set in Canada, there’s a virus in broadcast media–and detonated the connective tissue of reality into a strange new mess.

The novel opens with the narrator matter-of-factly explaining that he and his wife Claire are about to abandon his teenage daughter, Esther. As your first clue that a strange warping has occurred, what he describes at first sounds simply like a mouthy teenager, and you raise an eyebrow at the overreaction. Although, there’s no denying it, teenagers are often a bitter pill for parents to swallow.

But very soon, you’re sucked in by both the stakes–no, the voices of children are actually sickening adults–and the taut, daredevil moves in each sentence. Here’s a bit from Chapter Five, still early on:

But in Wisconsin there were early adopters. A fiendish strain of childless adults who consumed the toxic language on purpose, as a drug, destroying themselves under the flood of child speech. They stormed areas high in children, falling drunk inside cones of sound. They gorged themselves on the fence line of playgrounds where voice clouds blew hard enough to trigger a reaction, sharing exposure sites with each other by code. Later these people were found dried out in parks, on the road, collapsed and hardening in their homes.

This isn’t satirically motivated–it’s Marcus’s way of reifying a gestalt gone gooey. The viral speech is just the beginning of his rabbit hole. Reconstructionist Jews, Sam informs us, or “forest Jews,” build huts connected by underground wires that allow them to secretly listen in to rabbinical talks, in areas where synagogues aren’t available or perhaps wanted. In this world, even the fringe conspiracy theorists aren’t what they seem.

I wouldn’t say Marcus knits together these separate strands–virus fears, meaningless wasting disease, teenage anarchy, a marriage’s battered heart, spiritual questing, interrogation of language–so much as plays upon each catgut strand, creating weird, “gelatinous” chords of anxiety, peculiar in reach to our time, not least the disquieting interfacing of human being and information technology.

It is not, perhaps, the best book for anyone suffering with asthma to read, as Sam describes the speech virus’s progression in the throat and how hard it is to breathe. But there I was at midnight, uncomfortably close to a hallucinatory participation with this hallucinatory text, unable to put it down, fumbling for the albuterol.