It’s a nationwide trend: As jobs return, so do public transit passengers. The American Public Transportation Association says a record 10.5 billion trips in 2012 would have closer to 10.6 except for the impact of Hurricane Sandy on all modes of public transit along the Eastern seaboard. The association attributes the “second highest annual ridership since 1957” to the cost of gas and an improving employment picture. (Thanks to the Slog, who alerted me to the study.)

Currently, the national average for a gallon of gas is $3.69 for regular, $4.01 for premium. (The highest recorded average was summer of 2008: $4.11 for regular.)

In a related Reuters story, APTA spotlights Seattle, “where transit rides rose 11.8 percent over the year as the metropolitan area added more than 30,000 jobs.” From January 2012 to January 2013, the state of Washington added some 65,800 jobs (98 percent of which were in the private sector), with the unemployment rate now holding steady at around 7.5 percent statewide, 6.3 percent in Seattle.

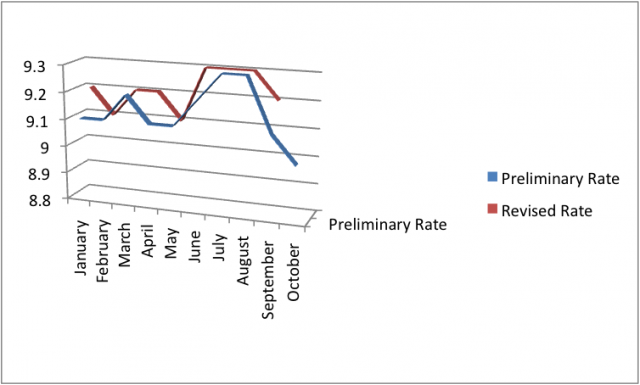

SIDEBAR: In fact, the state can’t quite believe the numbers are as good as the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics says: an increase of 24,100 jobs from December to January that may not be wholly new jobs, but may be due in part to seasonal adjustments and a change in the way the BLS reaches those figures. “Based on historical patterns,” explains chief labor economist Joe Elling, “Washington employment typically falls by 61,300 from December to January.” This year, the BLS estimated a loss of just 37,000, resulting in that “jobs increase” of 24,100. Elling expects these preliminary numbers to be revised to be more in line with an observed 5,000-jobs-per-month trend.

Nonetheless, Seattle is all over the APTA report on top transit ridership in the country during 2012. The Seattle Streetcar‘s ridership jumped five percent (750,294 boardings in 2012), with its First Hill line due to open in spring-summer of 2014 — and that line’s ridership is projected to exceed that of the South Lake Union stretch of rail. (There’s an ongoing fight to bring back the Waterfront Streetcar service, which used to carry several hundred thousand passengers a year as well.) Sounder commuter rail was up eleven percent (more than 2.8 million boardings in 2012), as was Central Link light rail (8.7 million boardings, up almost one million from 2011), reports Sound Transit.

King County Metro’s workhorse bus system carried 4.6 percent more passengers, as well — more than 115 million trips. Some of the boost in ridership can be credited to Viaduct Replacement Project construction and tolling on SR 520, says Metro chief Kevin Desmond, who has to fight for funding to maintain service levels, let alone deal with ridership increases. (Video of Desmond making his case available at Seattle Transit Blog.)

Funding for transit infrastructure is also up: “Last year 49 out of 62 transit-oriented state and local ballot initiatives passed,” said APTA President and CEO Michael Melaniphy, arguing this represented a sea change in public willingness to pay. The rise of transit dovetails with findings in a mid-2012 study, commissioned by the U.S. Conference of Mayors, that tied U.S. metro economies to transportation infrastructure. Have legislators understood this? Seattle Times columnist Jon Talton, whose article surfaced the report for me, wonders.

“If Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue were a separate country — and many legislators in Olympia apparently believe this to be so — it would have the world’s 53rd largest economy, just behind Israel and ahead of Portugal and Chile,” Talton writes. That $242-billion economy (in 2011) placed Seattle twelfth out of 363 U.S. metros, behind Boston (9th) and San Francisco (8th). It’s in the neighborhood of those of the states of Missouri, Louisiana, or Connecticut. In the decade between 2001 and 2011, it grew an average of 4.4 percent each year.

Taken together with Olympia, the Seattle MSA accounts for more than 70 percent of Washington’s economic product, with about half of the state’s nearly seven million inhabitants. By 2042, the study authors expect the Seattle MSA to grow 40 percent, to nearly five million. By 2020, they anticipate another 285,000 jobs.

Interestingly, since 2000, Seattle’s congestion costs (figured by cost of gas and driver time) have actually fallen: to $942 per year in 2010 versus $1,102 per year a decade earlier. That puts the Seattle MSA in tenth place nationally, behind Boston (9th), Denver (8th), and San Francisco (7th).

Congestion also impacts freight tonnage, where Seattle is twelfth, ahead of Boston this time, but behind Minneapolis. Usually, exports represent between 15 and 16 percent of Seattle’s gross metropolitan product (that ratio changed during the recession, edging into the 20s as exports stayed strong).

“Investment in roads, rails, and other forms of transportation,” claim the authors, “will help relieve the bottlenecks impeding economic expansion,” though they also write that “road capacity has not kept up with passenger growth, and public and alternative transportation usage and development has not been substantial enough to pick up the slack.” They also envisioned the average price for a gallon of gas falling to $3.11 per gallon at the end of 2012 (remember it’s around $3.70 now).

Doesn’t it seem that, in metro areas particularly, public transportation would come first, with roads taking up the slack?

The demand for transit in Seattle seems an indicator that the current ratio of roads to transit is unappealing to metro voters. A $10-billion transportation package unveiled by the state’s House Democrats would spend the vast majority of that $10 billion on new road projects, with $1 billion for maintenance and even less than that for public transportation. It does not help fund the 520 floating bridge replacement, which remains more than a billion dollars short, or the SR 99 tunnel. It doesn’t sound like it has yet sunk in, as STB announces, “Transit Supporters are the Key Swing Vote.”