Earlier this week, I posted about the growing concern that Colony Collapse Disorder may be driven in part by bees' exposure to clothianidin. Clothianidin is part of a class of systemic pesticides known as neonicotinoids, and they have been used widely across U.S. agriculture since the early to mid-1990s. "Systemic" refers to the fact that the pesticide pervades the plant it's applied to entirely, and so any troublesome insect that takes a bite of any part, from root to leaf, will be poisoned.

Earlier this week, I posted about the growing concern that Colony Collapse Disorder may be driven in part by bees' exposure to clothianidin. Clothianidin is part of a class of systemic pesticides known as neonicotinoids, and they have been used widely across U.S. agriculture since the early to mid-1990s. "Systemic" refers to the fact that the pesticide pervades the plant it's applied to entirely, and so any troublesome insect that takes a bite of any part, from root to leaf, will be poisoned.

When bees began dying off in large numbers in Europe, the precautionary principle was employed and neonicotinoid use was restricted or banned. (With interesting bee-bounceback results.) In the U.S., where the EPA professes to have no conclusive reason to act, beekeepers have been left to enforce their own boycott.

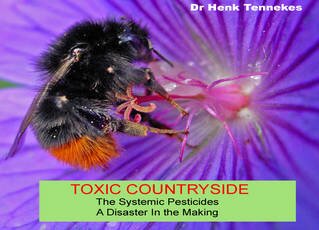

A SunBreak reader alerted me to the work of Dutch toxicologist Henk Tennekes (not the climate change impact skeptic), and his research that concludes honey bees and birds can scarcely help being affected by neonicotinoids. "Improper" use of a pesticide is one thing, but his 72-page, heavily footnoted scientific treatise, A Disaster in the Making, demonstrates that this class of pesticides is unsafe in any hands.

"It is a serious ecological report rather than a book for general readers," warns the website, but a serious ecological report is exactly what is required. Tennekes explains in this podcast that neonicotinoids are persistent in the environment in two ways: first, they can be active for months in plants they're applied to, but more importantly, their neurological effects (a dérangement de tout les bee sens) may be irreversible.

Neonicotinoid insecticides act by causing virtually irreversible blockage of postsynaptic nicotinergic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the central nervous system of insects. The damage is cumulative, and with every exposure more receptors are blocked. In fact, there may not be a safe level of exposure....

(more)

First, how does "Environmental Dereliction Agency" sound? I feel like "Protection" is really giving people the wrong idea about the actual results of EPA regulation.

Second, I should warn you that if you continue reading, you'll be begin to wonder how we're all not dead yet. Thanks to Grist's Tom Philpott, I was just alerted to the leaked EPA documents that show the agency's fumbling approval of a broadly used, very toxic pesticide.

It's been on the market since 2003--bringing in $262 million in sales in 2009 alone says Philpott--but a key study on the pesticide's safety was not produced until 2007. And now, EPA scientists have in essence repudiated that study's findings, though EPA officials didn't think the public needed to know that.

A little while ago, I went to see a documentary about Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), Colony, at the Northwest Film Forum. While it was really about beekeeping as a vanishing way of life, the film did track the efforts of David Mendes, the president of the American Beekeeping Federation, to lobby a German pesticide maker, Bayer, into researching more carefully the impact of their product Poncho (clothianidin). Mendes' fixation on pesticides was surprising to me because the word was that CCD was probably related to a fungus and viruses. (Mendes argues that if you poison people, we'll be more likely to pick up odd funguses and viruses, too.)

I have to admit, when I first heard Bayer, I thought it was odd the aspirin people were implicated in this, but of course they are a huge company, and crop sciences is another division. In any event, Mendes' interest in their pesticide Poncho becomes clearer once you know that it's absolutely clear that it's toxic to honey bees; the only question is, how would the bees be coming into contact with it?

Bees come into contact with a lot: a study on pesticide burden conducted across 23 states in 2007-08 found that:...

Remember the bee crisis? I still remember the peculiar mixture of disbelief and shock that arrived with the news. Bees, such indomitable, energetic creatures, were mysteriously dying off. And you know what? The epidemic is still in full swing: The U.S. honeybee population may be in terminal decline.

At the final screening of Queen of the Sun at SIFF, I spoke with Portland filmmakers Taggart Siegel and Jon Betz about their wild, entertaining, and thoughtful documentary on global bee health and welfare. Local note: cellist Jami Sieber did the score. (They're working on a theatrical release, so stay tuned. I vote for "Mead Night" at Central Cinema.)

Siegel mentioned he remembers the shock to his system when he first saw an article on colony collapse disorder, years ago. At the time, his daughter was three years old, and he had visions of the fruitless, un-pollinated world that might await her.

Bee fact! "The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that about one-third of the human diet is derived from insect-pollinated plants and that the honey bee is responsible for 80 percent of this pollination." No bees, no almonds, apples, avocados, blueberries, cantaloupes, cherries, cranberries, cucumbers, sunflowers, watermelon....

I know, if you survey a shelf of recent documentaries, you might be tempted to conclude that the jig is up, and we might as well all look into assisted suicide. We plunge from crisis to crisis, from peak oil, global warming, and global economic meltdowns, to food that's killing us, superbugs, and the autism epidemic.

But while Queen of the Sun opens with colony collapse, and spends time rounding up the likely suspects (varroa mites, the acute paralysis virus), Siegel and Betz have really made a poignant film about relationships. Siegel said that while he started making the film as a response to the crisis, he soon realized that human-bee relations (out of balance as they are currently) was his real, more instructive subject, not a parade of people saying, "There's a real problem here! And here's how we solve it." He and Betz decided that there was an untold love story that needed telling, instead.

And they would add one more twist....

Most Recent Comments