Izabel Mar as Pearl and Zabryna Guevara as Hester (Photo: Chris Bennion)

Izabel Mar as Pearl and Zabryna Guevara as Hester (Photo: Chris Bennion)

"I learned about my family in bits and pieces," playwright Naomi Iizuka said in an interview. "There are things that still peek out in the telling, like my father's sister will tell me something he neglected."

Similarly, you only get bits and pieces of Hawthorne's story in her play The Scarlet Letter, showing at Intiman Theatre (through December 5).

Audiences I think would be better served by knowing that Iizuka's work is to Hawthorne's as Kaufman's Adaptation is to The Orchid Thief. (Except that Iizuka's adaptation runs just over 70 minutes; you've hardly sat down, it seems, when everything is all done.) In both cases, the adapting author has introduced a significant personal element into the source. Here, that includes a paraphrasing of that "bits and pieces" line by the adult Pearl (Renata Friedman) who introduces and narrates the proceedings.

It's not a satisfying reworking, in that it hardly improves upon the original, and never makes a bold claim for its new existence--just like the little Pearl in the play who would like to be noticed but doesn't realize the attention the town fathers pay her is not for her sake.

Rather than a Puritan costume drama, what you see is a sort of memory play--part imagination, part hallucination--in which Pearl tries to recover her father, and make peace with the choices her mother made. (Tangentially, I direct you to Susan Faludi's "Feminism's ritual matricide.") Where Hawthorne's story is driven by Hester's conflict with Puritan society, Iizuka's play is not driven much at all, though it pretends to be (by a repressed memory that arrives right on cue)....

This is out of left field:

Intiman Theatre Board President Kim Anderson announces that Melaine Bennett, Intiman’s Director of Development, has been appointed the theatre's Acting Managing Director, succeeding Brian Colburn. The Board of Directors accepted Colburn's resignation for personal reasons, effective November 1, 2010.

The odd shake-up comes on the heels of two productions--Lynn Nottage's Ruined and a new adaptation of Molière's A Doctor in Spite of Himself by Christopher Bayes and Steven Epp--that both "exceeded their attendance and single-ticket goals," according to the theatre.

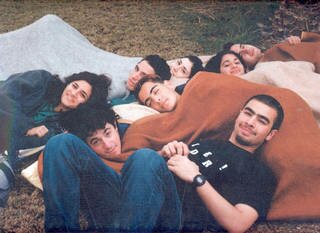

Asel Asleh and fellow "Seeds of Peace"

Asel Asleh and fellow "Seeds of Peace"

"It explores what it means to be a Palestinian inside Israel, which is in many ways different from being a Palestinian in the West Bank or Gaza." Her play is similar to a documentary, Marlowe said, in that she didn't create any of the dialogue between the young man and his sister--it's all based on her own interviews with the family, emails he left behind, and transcripts from the Israeli inquiry into the incident.

There Is A Field opens this week for a short run in Seattle, September 30 to October 3, at Capitol Hill's Shoebox Theatre (1404 18th Avenue). The timing marks the tenth anniversary of what Palestinians living in Israel refer to as "Black October." Marlowe explains the tragic history:

As the second Intifada erupted in the West Bank and Gaza, demonstrations also began in Arab villages inside Israel. In October 2000, twelve Palestinian citizens of Israel were killed in these demonstrations by Israeli security forces. One of those killed was a seventeen-year-old boy named Asel Asleh. He was shot point blank in the neck by Israeli police at a demonstration outside his village.

Asel, a participant in a peace program called Seeds of Peace, was wearing a Seeds of Peace T-shirt at the time of his killing and was buried in it. Marlowe has chosen to tell the story of Asel’s life and his death from the perspective of his older sister, Nardin. The play opens with Asel's death, and then explores Asel's idealism in light of the bitterness and grief Nardin feels, as she weighs her own commitment to seeking peace.

The play's title is taken from a line by Rumi. Asel referenced it once as he was struggling to make sense of his obligations, his duties: "Out beyond ideas of right-doing and wrong-doing, there is a field. I'll meet you there."

In Seattle, six actors will perform a semi-staged version, reading from scripts to highlight that fact that, as Marlowe says, "every word in the play was said or written by someone." Meanwhile, this is just one part of a "theatrical call to action" that Marlowe is spearheading. As of last week, 30 performances and readings of the play were planned in 15 countries (and in eight languages).

One is taking place in Derry, Ireland, because some Bloody Sunday families feel a kinship between their stories and that of Asel's family. This is the larger context of the play, what it means to be a marginal population at "home," the suspicion and police brutality, the competing cultural claims and loyalties. After each performance, there will be a discussion hosted by a Palestinian who grew up in Israel.

Steven Epp, Don Darryl Rivera, Allen Gilmore and Daniel Breaker in A Doctor in Spite of Himself at Intiman Theatre. Photo by Chris Bennion.

Well. If this weekend isn't the weekend that the fall performing arts season kicks off! Your options are so rich and varied that On the List really just doesn't do it justice, so here's your one-stop shopping center of performance openings.

LATE EDITIONS: John Longenbaugh's new play Arcana is opening at Open Circle Theatre, ArtsWest presents Neil LaBute's savage comedy Reasons to Be Pretty, and Saturday, Sept. 11, you can stay up all night at the Hedreen Gallery's Face Time with Anne Mathern and the inimitable Mike Pham.

Stokeley Towles, Trash Talk: The Social Life of Garbage (opening Sept. 9; tickets $5-$12) I caught Towles' last show Waterlines, in part just because it seemed like such an odd concept: a one-man show about the municipal water system. And yet it blew me away. Towles is a brilliantly subtle performer and engaging thinker who sucks his audiences into the fascinating world of the otherwise banal social services we take for granted; he manages to make really excited about it without falling back on Bill Nye-style fake exuberance. In Trash Talk, Towles moves on from water to garbage, crafting a fascinating portrait of how we related to what we throw away. Definitely not to be missed.

Strawberry Theatre Workshop, Breaking the Code (opening Sept. 10; tickets $15-$30). Mathematician Alan Turing earned his page in the history books for playing a role in breaking Germany's infamous "Enigma" code during the Second World War. Perhaps he was so good at solving riddles meant to hide the truth because in essence, he was one himself, a closeted homosexual trying to hide his true self from the world. Emotional drama will ensue. I wouldn't normally be all that interested in a show like this (they're a dime a dozen, frankly), but it's hard not to get behind Strawshop, consistently one of Seattle's finest theatres and a company that's developed something of a rep for doing engaging bio-plays.

The Balagan Theatre/Eric Lane Barnes, Rapture of the Deep (opening Sept. 10; tickets $15-$18). A semi-autobiographical play by Barnes, Rapture of the Deep tells the story of a kid who grows up in the larger-than-life shadow cast by his dead uncle. This also happens to be the last production to go up in the Balagan's current Capitol Hill space, so if you have fond memories, be sure not to miss your last chance....

Danyna Hanson's "Gloria's Cause," part of the TBA Festival starting this weekend in Portland. Photo: Ben Kasulke.

If there's one thing Seattle sadly lacks, it's a big festival of contemporary performance, like Austin's Fusebox, New York's Under the Radar, or even Vancouver, B.C.'s PuSH. Yes, On the Boards brings in touring artists like that all year long, as well as serving as an incubator for local talent. And Theatre off Jackson does, too (them being, in their own words, "the working women's On the Boards"). And finally, there's plenty of smaller presenters doing the leg-work to bring high quality art to Seattle (did you know that Paula the Swedish Housewife is bringing in Taylor Mac for an intimate, one-night-only performance at Oddfellows?).

Well, as much as we all may wish that, on top of all that, we could be subjected to a big, two-week festival as well, it ain't happening anytime soon. But a short drive down to Portland this September gets you to the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art's 2010 TBA Festival, one of the country's premier showcases of performance (with film, music and visual art thrown in).

Starting Thursday, Sept. 9, Portland plays host to a fantastic line-up of artists from around the world, as well as showcasing some of the Northwest's top talent.

On the theatre front, the first weekend features a pair of amazing solo performers. Mike Daisey is already pretty well known in the Northwest, having began his career as a lectern-based monologuist in Seattle, tackling the New Economy absurdity of Amazon.com. For TBA, he's returning to similar territory with The Agony and Ecstasy of Steve Jobs, a new work which explores the rather unpleasant process by which Apple's beloved products are made in Chinese factories where workers toil in subpar working conditions. Also appearing is Conor Lovett of the Gare St. Lazare Players, performing two of Samuel Beckett's prose pieces as monologues. If that sounds odd, trust me, it's not to be missed. There's a long tradition of presenting Beckett's prose work theatrically (it's laugh-out-loud funny), and this weekend I did a phoner with Lovett, so expect more soon....

The Columbia City Theater (Facebook) is a music club to fall in love with. It re-re-re-re-opened (the old vaudeville hall has been around since 1917, in various guises) in June of this year, and vaulted into the Seattle Weekly's "Best of Seattle" list less than two months later.

Before we go behind-the-scenes, here's the lowdown. You'll find the Theater at 4916 Rainier Avenue South, which is just beyond the Columbia City Cinema. (Take the #7 or #8 bus or light rail--the last light rail train leaves SeaTac for downtown at 12:10 a.m., Monday through Saturday.) It's adjacent to the award-winning pizzeria Tutta Bella, who serve up the eats in The Bourbon, Columbia City Theater's bar. The bar is open seven days a week, 4 p.m. to 2 a.m.

The bourbon-heavy cocktail list ($8-$10) features pre-Prohibition favorites (Mint Julep, Derby, Commodore), as well as some rye (Red Hook; Fratelli Cocktail, with Fernet Branca; Diamondback). Bar entertainment ranges from djs to karaoke to live music, and on nights when there's a show in the theatre, you can watch the show projected live on a screen. Happy Hour most of the week is 4-7 p.m., and all day Monday, and brings you such wonders as $5 pitchers of High Life and $3 wells.

Past the bar, on your left, is the entrance to the theater, which has a bar of its own. It's an intimate shoebox space, though it holds over 200, and the acoustics require no over-amplification. The ambiance--the curtained stage and brass lighting fixtures and brick walls--makes this unlike any other music club you're likely to step into in town....

Molly Rivers (Renata Friedman) meets her idol Margot Mason (Suzy Hunt) in ACT's "Female of the Species." (Photo: Chris Bennion)

With Female of the Species (at ACT Theatre through July 18), Australian playwright Joanna Murray-Smith is more interested in making you laugh than in feminist critiques, although laughing at the self-importance in feminist critiques is more than welcome.

It's a drawing-room farce that just happens to have a feminist icon in its particular drawing room (a creation of set designer Robert Dahlstrom). ACT's uniformly strong cast is rotated in throughout the course of the 100-minute play, so there's never a dull moment, or even room for an intermission. The play just caroms along, merrily knifing sacred cows. It's long on gleeful satire...and less well-supported by character and plot development.

The set-up, briefly, is that feminist monstre sacré Margot Mason (the gimlet-eyed Suzy Hunt) is grinding out another zeitgeist-hash-settling book, or should be, when her writing and writer's block are interrupted by an unexpected, uninvited visitor, former student Molly Rivers (Renata Friedman, doing a farce-version of Thewlis in Naked). Molly is a particularly demanding fan, it turns out, but she's not the only one with a manifesto. Mason's daughter, her daughter's husband, her daughter's taxi driver, and her editor will all have their say as well.

While the play has some trenchant things to say about being a woman today, there's no Women's Studies pre-req, or at least no one asked at the door. It's not, for instance, necessary to know that it was inspired by Germaine Greer being held hostage for two hours by a teenage stalker, before dinner guests arrived. (Or that Greer, born in Australia, once described her native land as an ocean of suburban mediocrity.) If the book title Cerebral Vagina makes you laugh, this is the play for you.

And in that case, go buy a ticket and stop reading because here there be spoilers.

Female of the Species should have an intermission, but doesn't, because there's nowhere to put it. The play doesn't reach a climax so much as get distracted. Margot Mason's enlightenment--that she can take the weight of the women of the world off her shoulders--arrives on cue in the closing minutes but is hardly believable. It's sort of a well-meant gesture, rather than any light catharsis....

I can't say this staging of On the Town (at the 5th Ave through May 2) is a laugh riot--but the sight gags never stop coming and eventually they outpunch you. From the set's giant-poster backdrops of New York to the acting for the back row, this is not a show long on nuance. It's brassy, in your face, and intent on being broad as Broadway gets.

Director Bill Berry and choreographer Bob Richard ride a comedy two-speed: it's either high-speed Keystone Cops up there or outtakes from the Carol Burnett show. But there are also Jerome Robbins dances that are a dream of New York, its hustles and cons, carnival vitality, springtime breezes, and boozy nightclubs. And of course, there's the irrepressible score from a young Leonard Bernstein (this is part of Seattle's Bernstein fest).

While this production plays up what's dated about On the Town (the sailors are G-rated kids, the women kooky), the magic of "shore leave" in New York is immortal--unless you live there, you're always on a schedule, always wide-eyed, and always on a subway to...somewhere, you'll find out. The show's book and lyrics, by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, offer a wit in addition to yucks, but Berry is after low-hanging fruit, not forehead-furrowing double entendres. The acting is mostly delivery....

Clifford Odets always makes me think of the opening of the Coen Bros.' Barton Fink, John Turturro listening offstage to impassioned lines like:

Not this time, Lil! I'm awake now, awake for the first time in years. Uncle Dave said it: Daylight is a dream if you've lived with your eyes closed. Well my eyes are open now! I see that choir, and I know they're dressed in rags! But we're part of that choir, both of us--yeah, and you, Maury, and Uncle Dave too!"

And then comes the call of the fishmongers.

It's an affectionate shot to the ribs, but what you learn watching Intiman's Paradise Lost (through April 25, tickets here) is that Odets was--as any great playwright is--overflowing with voices, not just firebrands urging revolutionary singalongs. Yes, he was also a bubbling fountain of what Arthur Miller called "unashamed word-joy" but a good deal of the joy (and words) came from what he heard around him. How people speak in Paradise Lost is often how they spoke--"Have a piece of fruit," "Do yourself a personal favor," "We're like that for each other"--with no adornment; it's in the soliloquies (arias, really) that the language takes wing and the words sing.

Dramatically, not much separates Paradise Lost from a Chekhov play. An upper middle-class family, the Gordons, is coasting slowly to the end of their charmed, aristocratic life, unable to adapt to the social upheaval all around them. As the play begins, in 1933, the cracks produced by the Depression are just starting to show in the solid walls of their home. (That's my metaphor--the set by Tom Buderwitz actually features a trompe l'oeil scrim of brick and siding that, with L.B. Morse's lighting, exposes a disturbing insubstantiality to the Gordon home.)...

Rachel Permann and Martyn G. Krouse in Fat Pig. Image courtesy of Artattack Theater Ensemble.

Artattack Theater's new space at Olive and Bolyston is absolutely perfect for the company's first production there. Neil LaBute's Fat Pig is all about uncomfortable intimacy, and that's exactly what the space conveys. The stage is in the middle of the room, with two rows of chairs along opposite walls. As a member of the audience, you are very, very aware that you're not watching the play alone, but rather serving witness with others in an emotionally claustrophobic environment.Director Justin Lockwood claims Fat Pig's characters are trying to do well, but that's just not true. LaBute's characters are always sociopathic at best, psychopathic at worst. And the work itself is typical LaBute: casual cruelty, people being terrible to people, although at least in this play, no one ends up dead or maimed or otherwise physically harmed. Spoiler alert?

Instead, boy (Martyn G. Krouse as Tom) meets girl (Rachel Permann as Helen), and they really like each other--Krouse and Permann both bring some seriously sexy, flirtatious heat. Too bad traditionally handsome Tom can't get over the fact that Helen has some meat on her bones. Though smart, anxious Helen is ostensibly the titular character, Fat Pig is not so much her story, as the story of everyone's reactions to her. Tom's immature work frenemy Carter (Lockwood pulling double-duty and relishing the douche-otype) has his own weight hangups, while a girl at work Tom used to date (Lisa Every as Jeannie) can't get over the fact that he'd rather date a fatty than her crazy ass. Bland, weak-willed middle manager Tom just doesn't have a clue how not to care about what others think....

David Mamet's "Edmond" at the Balagan Theatre, directed by Paul Budraitis. Photo by Andrea Huysing.

"I wound up in Seattle because I was going to Indiana University, and I was about to graduate so I was looking into my options," Paul Budraitis said. "I was pretty much set on going to Chicago, and then a few things happened that kind of made me reconsider. And I wound up talking to somebody that was heading to Seattle, a grad student, and she sort of sold me on the place, saying at least it was worth checking out."

About a week before the opening of David Mamet's Edmond at the Balagan (through Feb. 6, tickets $12-$15), which Budraitis directed, he and I met up at Caffe Vita to chat about his history and work. Tall and solidly built, Budraitis has a calm voice but gives off a vibe of quiet intensity that was only heightened by his deferral to wait in line to get a coffee for himself, mysteriously offering only that it did "something" to him and it was probably better that he didn't have any before heading to rehearsal. This all left me imagining him a pent-up ball of over-caffeinated aggression, à la Henry Rollins, though that owes as much to a video I once saw of his solo performance as anything to do with the man himself.

Budraitis, whose family emigrated from Lithuania, moved to Seattle in 1995 and spent the next five years working in fringe theatre. His time at Annex Theatre was particularly formative, because it was where he first learned Vsevolod Meyehold's biomechanics method, which continues to inform his theatrical approach. But in 2000, he left to go to grad school in Lithuania, where he trained under the legendary director Jonas Vaitkus, who, along with Oskaras Koršunovas and Eimuntas Nekrošius, helped put Lithuania on the global theatrical map with a radical aesthetic approach developed in the crucible of Cold War repression....

Jade Justad as Angela in 3Sisters.Cz at GESAMTKUNSTWERK!

If you are going to name your new theatre company GESAMTKUNSTWERK!, you may as well found it in Seattle, North America's operatic answer to Richard Wagner's Bayreuth. Wagner didn't invent the "total artwork" term, but it was his dream for his operas.The fledgling theatre company makes heroic attempts to synthesize media and experience in its first fully-produced play, 3Sisters.Cz by Czech actor/playwright Iva Klestilová (two shows left, January 29 & 30; tickets: $10-$15). Hoses spray real water, screen projections display a fiery apocalypse, rain pours off awnings over the audience, radio announcements are piped in, televisions turn on--it's astonishing in a fringe theatre production.

But you may also be astonished by the play itself, which is only in the loosest sense "based" on Chekov's Three Sisters--largely in that there are three sisters in this play, as well. It's set in the Czech Republic in 2002, and director Dani Prados notes that rather than trying to fit Chekhov's plot into modern-day life, Klestilová "preserves the emotional cores of these complex individuals." I did not find that to be the case, unless you felt that a Lucian Freud portrait preserved the emotional core of, say, the Mona Lisa.

I think it would be more honest to describe the play in terms of its creation--a Czech actor playing Olga in Three Sisters develops, in a conflation of that experience with the social stresses of her country--her own nightmarish vision of sisterhood: debased, frustrated, and neurotic....

Shag (Anthony Heald) takes notes as his actors flesh out his script (from left, Gregory Linington, John Tufts, Jonathan Haugen). Photo by Jenny Graham.

It's your last weekend to see Equivocation at the Seattle Repertory Theatre (7:30 p.m. Fri-Sun, with a 2 p.m. showing on Sat-Sun; $12-40). The play really comes down to the three Bills: writer Bill Cain, director Bill Rauch, and protagonist Bill Shakespeare. But this isn't the Shakespeare you think of, the erudite playwright who just happens to be the Best Writer EVAR. Nope, Equivocation's Shakespeare is known as "Shagspeare" or just "Shag," a guy who's still struggling with his craft, who has family issues and writer's block and deadlines just like the rest of us. And he's played by Anthony Heald, who you immediately recognize as That Guy, since he's been in everything. (He played the weaselly principal on Boston Public as well as the weaselly doctor from Silence of the Lambs.)

Equivocation premiered last year at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, and everyone involved remains intact for the Rep run. The nearly three-hour play is ostensibly about Shakespeare writing a new work. He's still workshopping King Lear when King James' chief adviser, the hunchbacked Sir Robert Cecil, approaches him to commission a play about the King defeating the perpetrators of the Gunpowder Plot (that's Guy Fawkes, et al, attempting to blow up Parliament, if you haven't seen V for Vendetta). The Bard tries to dramatize this non-event, but he finds it challenging to write a play that's nothing more than political propaganda. Because even in the 1600s, no one wants to be a sellout. Equivocation is of course also about "equivocation," the idea of toeing the line between truth and lie. It's an important and completely relevant idea, but as a theme, it kinda gets old real fast. I get it; I have watched the Colbert Report and know all about truthiness, thanks....

Harold Pinter's "Betrayal" at Seattle Repertory Theatre, 2009

This is the first of a three-part series on the scenic design work of Etta Lilienthal. Click here for part two, or follow this link for a gallery of her work for theatre and dance.

Set design is one of the trickiest yet least appreciated elements of theatre production, mostly because audiences only really notice the design when it's bad. A bad set makes you aware that it's not working, and draws you away from the action. A decent design (and most design, even at the big regional theatres, is only decent) works because you don't notice it. It's a backdrop that doesn't distract, a functional space for the performance to inhabit.

A truly great design, on the other hand, is usually so integrated into the production that audiences assume that most of it is purely the director's concept. It's hard to imagine the designers, rather than the director, playing such a profound role in generating the collaborative synthesis that's determining where the actors are onstage and what they're doing, let alone to imagine, as happens from time to time, that the very concept you're seeing onstage may have been primarily the idea of the designer, who had to sell it to a skeptical director.

Etta Lilienthal is one of only a handful of scenic designers in Seattle who creates great sets. A long-time collaborator with choreographer Maureen Whiting, with whom she's done some of her best work, Lilienthal has designed sets for everything from big shows at Seattle Rep to solo performance pieces staged in little Capitol Hill theatres. She's also worked in film, serving as the production designer for both Police Beat and the ill-fated Cthulhu, and in addition to recently finishing an art design job with The Details, a Tobey Maguire movie that was filmed in Seattle, she designed the set for Seattle Rep's Opus, which opens this week.

A few weeks ago, I sat down with Lilienthal at Victrola on Pine Street for a wide-ranging discussion of her work. Swiss-born but raised on Martha's Vineyard, Lilienthal has a slight build with short-cut, curly hair and a clever, knowing gaze. The daughter of a carpenter father and an artist mother, Lilienthal attended Smith College for two years, including a semester abroad studying textiles in Scotland, before transferring to CalArts, where she completed a BA in theatre and an MFA is set design.

"I don't usually say yes to a project unless I'm really interested in collaborating specifically with that director," she said of her varied work choices. "Now, that's not always the case, obviously sometimes you take work regardless."

"In general, I have a really open approach" to designing a show, she said, "and I really want to hear what they [the directors] see, and if there are really specific things that are, for them, like, 'We must have this, for this show.' Or ideas they have, very specific images. And then I read the play several times, I meet with them several times, and then I start to develop my own vision. And it's just basically images coming into my mind, and if I'm stuck, or the way that I start, is by sketching, and often by going in and flipping through books in the library, just art books—very often contemporary art books. Just to sort of spark strong spatial relationships and color relationships. Sometimes I'll fixate on a particular image that might be very realistic, or sometimes I'll see, for instance, an installation that's actually very abstract that I feel is somehow a very interesting space, and I can see the play living in that somewhat abstract space."

"Abstraction" is a good way to describe Lilienthal's work. Rather than thinking realistically ("I personally don't like to go to the theatre to see things that I see all the time," she told me, "like my kitchen or my bedroom, so I tend to design from a place that's kind of in a dream and doesn't really exist in the world"), Lilienthal tends to approach design sculpturally, as a way to engage and make use of the particular performance space.

She talks a lot about the "volume of space" to be dealt with, and about the challenges different theatres—particularly ones with large vertical areas—present. Even her more realistic sets for traditional plays often skew the vertical and horizontal perspectives. In her design for David Auburn's Proof at Madison Repertory Theatre in 2002, she set the facade of a house angling upstage-right, veering away from the audience. For Nilo Cruz's The Beauty of the Father at Seattle Rep in 2004, she raked (angled up) the stage-floor as steeply as actors' union rules allow, about two inches per foot.

"It's hard," she said of the process of making such choices, of not only finding the right angles and perspectives but actually turning them into a functional design. "I'd say mechanical drafting is not my forte, and neither is math. But I'm very interested in what people see. So often when I want to skew perspective, or shift or change it, or force it down or extend it, I actually work in model-form. So I actually make a model, maybe a quarter-inch scale, and then I adjust shapes and move them around, and change my eye-line, and play with those shapes and volumes and shift them even slightly to see what kind of different feeling it gives.

"And it really is a feeling. It's like, that feels too angry. Sometimes you can shift a perspective so much that it's very aggressive. And maybe that's good," she added. "Or that feels too soft, or that's not doing anything for me."

This last year, Lilienthal did the design for two radically different but equally well-received theatre pieces: Seattle Rep's production of Harold Pinter's Betrayal, and Keith Hitchcock's mind-bending solo show Muffin Face, performed at the Balagan Theatre.

Betrayal was one of the highlights of an otherwise fairly rough season for Seattle Rep, and that came as a bit of a surprise. Betrayal is one of Pinter's mid-career plays, written after he'd given up on the avant-garde, menacing qualities of his earlier works like The Birthday Party and Homecoming. In many ways, it's a tame domestic drama, about an affair between a woman and her husband's best friend that unfolds over years. It's well-worn territory that even the best theatre artists can rarely breathe life into. But Pinter had one brilliant insight that helps make Betrayal work: the story unfolds in reverse, beginning with the devastating consequences of the affair and ending with the generally innocent beginnings.

That reversal forces the audiences to constantly reassess the narrative, since you only get the back-story to each scene after the fact. And it was this sense of reassessment and claustrophobic absorption in the story that influenced Lilienthal's set, which worked far better than even she anticipated.

The trick was simply a moving wall, that came forward about four feet at a time during the scene transitions, until by the end it's crowding the actors on the lip of the stage.

"As this wall moved, first it [just] moved, and the second time it covered a window, and then it covered another window. By the fifth time it moved, it was all the way downstage," she explained of the process. "Ninety-five percent of the audience told me they never saw the wall move, until they realized both windows were covered. Now, for me this was astonishing! And so many people stopped me and talked to me about this. They were totally stunned, and they sort of had to backtrack the entire play and re-imagine what was happening."

"I thought it would be, 'Oh wow! The wall's moving. Cool,'" she said sardonically. "Or, 'Oh interesting, the space is changing.' But I had no idea that people wouldn't notice it, and that they would be so affected by it, that it changed they way they knew and understood the characters and the space and the relationships."

Keith Hitchcock's Muffin Face is about as different from Betrayal as you can get. A surreal one-man-show in a tiny, intimate space, Muffin Face is the one show I'm positive too few people saw last season. The audience enters a theatre made up like a conference room, centered around a long table, but with numbered, assigned seats wrapping around it and seemingly inexplicable arrows drawn on the floor. Hitchcock, dressed in a gray three-piece suit and wearing a head-mic, enters and performs as something between a motivational speaker and an infomercial pitch-man, leading you through the "pre-show" to Muffin Face.

Essentially what Hitchcock does, through a variety of off-the-wall gimmicks and audience interaction, is to draw the everyday into hyper-focus for the audience when it leaves the theatre. The "pre-show" is all he gives you; Muffin Face (whatever that means) is your life afterward, and as promised, the effects of the show last until you go to sleep that night. It's akin to what it was like back in college to get high in your dorm room then stumble around campus at night, stunned by how weird everything seemed. "Profound" is perhaps too strong a word, but it was a stunning piece that did something to its audience that few works manage.

"You're coming at a space like that totally differently, because everyone is, like, two feet away from the performers," Lilienthal explained, chuckling at my reaction to the show. "That's when I like to get hyper-realistic, almost surreal. And that's what Muffin Face was for me. I was really interested in the idea of something that most people know very well—in this case, a board room or an office-style space—and making it kind of hyper, kind of extreme on that level."

But what Muffin Face really demonstrates is how a designer can play a fundamental role in crafting the overall work. I was surprised to find out from Lilienthal that there was no staging concept originally. The spoken text was all that Hitchcock prepared, while the setting—which was ultimately a huge part of the show—could have been anything, anywhere.

"I actually knew from the beginning that that was where it was going to end up at," Lilienthal commented slyly, in the one of the few moments she betrayed anything other than complete humility to the collaborative process. "But I don't get to say that to the director, and we went around and around, we went in this huge circle to get back to that. Because usually the vision I have in my head is right."

Other concepts proposed for the setting ranged from a prop warehouse to a bathroom (with Hitchcock performing in the tub) to a chemistry lab to the Bat Cave.

"All of those could actually have really worked well, and that was what was so tricky about this play," she explained. "There was a working script that was just words, nothing happens in it. It was one of the most intellectual projects I've ever worked on. Keith's an intellectual, I'm intellectual, and the two directors he worked with were very intellectual."

Ultimately, one of the biggest constraints on the design was the desire to make it tour-friendly. "From the beginning, he said, 'I want to make sure we can tour this,' so we had to pull way back, and get really, like, 'We're going to get these few items, that can come apart, fit into a car,'" Lilienthal said of the final choice. "And so it ended up going into a very simple place."

"But for me, it really preserved and hit on these really funny, key elements that even if it had been this really complicated chemistry lab...that might have even overshadowed the actual words," she continued. "He's a great writer, he's very funny, and I felt the set wasn't too overpowering, but it was strong, it was compelling. It had a strong character role that it played, but not one that was over the top of Keith. Because Keith needed to be bigger than the set, and a lot of our initial ideas were much bigger than Keith could have ever been."

Tom Stoppard's Rock 'n' Roll, which opened at ACT Theatre last weekend (through Nov. 9, tickets $10-$37.50), is all about how rock music expanded minds behind the Iron Curtain and helped liberate the masses from Communism. It's a swansong to the Sixties and buys into all the tired cliches about the power of music, particularly the sort that appeals to Baby Boomers.

Misha Berson loved it, but I didn't at all (I half wonder if we didn't see it on different nights), and not just because I don't like the themes. For instance, she wrote that, "Instead of the cumbersome slide projections in the Broadway staging of Rock 'n' Roll, ACT uses chalk, paper and spray paint to indicate the passing years. And Stoppard's specified sound clips of '60s rock (by Bob Dylan, the Doors, Pink Floyd, et al.) are smoothly inserted."

Personally, I think she's dead wrong on both counts there, which is just the beginning of the show's problems, but you're free to decide who to believe. All I can say is that when I was shown the above clip...

Robert E. Sherwood was one of America’s most celebrated literary figures of the 1930s and 1940s. As a playwright, screenwriter and historian, he won four Pulitzer Prizes, co-founded the famous Algonquin Round Table and saw his plays made into movies staring Bette Davis, Humphrey Bogart, and Clark Gable. He even won an Oscar.

But today, some 50 years after his death, he is virtually forgotten. His work is rarely shown on stage and, despite his awards and massive notoriety in life, he remains unknown to many of today’s theater audiences.

So it’s a delightful surprise to find that the Intiman is currently offering a sparkling production of Abe Lincoln In Illinois (tickets $20-$55), perhaps Sherwood’s finest play and winner of the 1938 Pulitzer for drama. Better still, they are staging it with the intelligence, insight and respect that it deserves. It just might rescue Sherwood’s reputation from oblivion. No one ever deserved a resurrection more.

Sherwood’s literary vanishing act is not really mystifying. He was a particular...

I need Bo Eason to tell me it's okay to watch football.

After seeing Eason's engrossing one-man show at ACT on Thursday, I don't know if I can do so guilt-free again. Watching the former NFL player act out the injury that helped end his career actually made me physically ill. No joke: Sweat pouring out of me, I excused myself down my row, and hustled to the bathroom to splash water on my face. I thought about the real scars on Eason's actor knees, about seeing him inject himself there on stage, as he did before games during his playing days.

And I thought about Curtis Williams, who in 2000 absorbed a fatal hit playing in a football game for the University of Washington. "He fell to his back and went into convulsions," teammate Anthony Kelley relates in Derek Johnson's The Dawgs of War , which I'd read earlier that week . "He was mouthing the words 'I can't breathe .' ... Then Curtis began spitting up and shaking, and his eyes rolled up in the back of his head." Williams died of his injuries 18 months...

Natalie Breitmeyer and Patrick Allcorn in "Neighborhood 3: Requisition of Doom" at WET

In Neighborhood 3: Requisition of Doom, which opened last weekend at Washington Ensemble Theatre (Thurs.-Mon., 7:30 p.m.; tickets $12-$18), playwright Jennifer Haley sets up two disparate concepts--violent zombie video games and suburban angst--as a pair of mirrors reflecting one another in a twisted dual-metaphor. Suburbia is a paranoid, isolated world of desperate souls struggling to survive the decline and fall of civilization, much like the heroes of pretty much any zombie scenario. Violent first-person video games, in turn, provide a license and outlet--and a frequently disturbing one at that--for the rage and sexual tensions that a buttoned-down, tidy society (like the suburbs) suppresses.

If that sounds a little juvenile, it is. Haley's view of suburbia has more in common with Nineties grunge and contemporary punk rock than with more the staid, "adult" explorations of suburban anomie we get from writers like Rick Moody. But somehow, it works. The story centers on a video game called Neighborhood 3 that all the teenagers are addicted to. Using satellite imaging technology, the game puts you in a horrific zombie scenario in your own neighborhood. The twist is, it's not entirely fictional....

As someone who's read more books on Abraham Lincoln than I have books of the Bible, let me say how much I'm rooting for Intiman's production of Abe Lincoln in Illinois.

Lincoln's rise from dirt-poor child to itinerant handyman to U.S. President, with stops in-between as a suicidal griever, duelist, and amateur poet, is more than a political triumph--it's a human one. Any attempt to spread Lincoln's story gets a push from me.

Last night Town Hall hosted a dramatic reading of the Lincoln/Douglas debates, with the leads from Intiman's upcoming production playing the respective oratorical contestants.

As Stephen Douglas, longtime Seattle actor R. Hamilton Wright brilliantly captured "The Little Giant's" power and pomposity.

As Abraham Lincoln, New York actor Erik Lochtefeld has a little farther to go, but the play doesn't open until October 2. The setting was a lecture hall, not a stage. And I'm a huge Lincoln snob.

That said: If I'm directing, I'd like to see Lochtefeld capture Lincoln's down-to-earthyness a little better. The script even references it; Douglas's "debate" speech in the play notes the contrast between Douglas' more traditional fiery oratory, and Lincoln's more natural speaking style; he used anecdotes and jokes to put his (often illiterate) audience at ease. Lochtefeld came across as professorial, not the right tone when playing a character who had less than a year of formal schooling.

I'm sure makeup, costume and another week of rehearsal will iron out the kinks. It's a fine line Lochtefeld has to toe--get too homespun and you sound like a Mark Twain impersonator, not enough and suddenly your doing John Edwards. I wish him luck, and look forward to seeing the finished product....

Brant reconstructs the true-life story of "Mary," an elephant in the Sparks Circus that was reputedly even bigger than Barnum & Bailey's famous Jumbo. In September 1916, Mary killed her new, inexperienced trainer when, unable to control her, he began harming her. The small-town Tennessee people who witnessed the violent death demanded Mary be put down, and in a perverse twist on Thomas Edison—who executed an elephant at Coney Island in 1903 in an attempt...

Most Viewed Stories

- Deep-Bore Tunnel Funding Still a Hot Topic

- McDonald's Adds Insult to Injury with Local Billboard Campaign

- Film Forum Spotlights Leonard Cohen, Small-Town Ohio

- EPA Can't Tell Difference Between "Beekeeper" and "Bee-killer"

- Why Will Smith, Joe Montana, and Wayne Gretzky Are All Coming to Issaquah Tonight

Most Recent Comments